Panama Photo Gallery

Sharks, Crocs & Prison at Coiba National Park

Located about an hour across the Gulf of Chiriqui by boat from Islas Secas, off Panama’s southern coast , the 503 sq km Coiba National Park is the largest island in Central America. Declared a national park in 1992 and a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005, Coiba was best known for 85 years (1919-2004) as a penal colony. Under the dictatorships of Manuel Noriega and Omar Torrijos, the place had a horrific reputation for extreme brutality, torture and politically-motivated executions. As a result, locals avoided Coiba like the plague.

The prison’s legacy ultimately proved a double-edged sword: Though inhospitable to humans, Coiba’s complete lack of development made it a haven for nature and wildlife. Around 80% of the island remains covered in ancient forest, including rare plant species you won’t find anywhere else in Panama. Since the prison was closed in 2004, the island’s wildlife has been thriving, and Coiba is now home to impressive numbers of Scarlet Macaws, Howler Monkeys, Agoutis, Crested Eagles and Crocodiles (most of which we saw during a short hike around the ranger’s station).

As impressive as Coiba is by land, its waters offer an even greater bounty of marine life: It’s surrounded by one of the largest coral reef systems of the Americas’ Pacific Coast, and the warm current of the Indo-Pacific makes the area a favorite among various species of fish, sharks, whales, sea turtles and rays. Researchers from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute have suggested that as many as half the species that populate Coiba’s waters may by unknown to science. So we figured, what better place to do our first-ever Discover Scuba dive?

After a bit of on-land instruction in the basics of PADI diving, we headed into the shallow waters off the Coiba beach. There, Mary and I learned how to strap ourselves into our BCs (a.k.a. Buoyancy Compensators), control our breathing through Regulators, adjust our weight and buoyancy, and ascend/descend safely. We also learned the various underwater signals we’d be using to communicate with our instructor once we got down below the surface. Before we knew it, we were in the boat on the way to our first-ever Scuba dive site, just off the shore of the picturesque islet Granito De Oro.

I’m not sure words can adequately convey what it’s like to be under the sea in a protected marine reserve for the first time, but this photo should give you some idea. We’ve been snorkeling dozens of times over the years, but nothing compares to being surrounded on all sides by huge schools of fish the likes of which you’ve never seen before.

We each had our respective difficulties adjusting to Scuba: For some reason I’ve always had trouble making my ears pop to equalize pressure underwater (done by pinching the nose, then exhaling gently), while Mary had issues controlling her buoyancy and wound up holding the dive master’s hand until she got comfortable. But gradually we made our way down to the bottom, slowly circling around the reef until we were in a depth of about 40 feet.

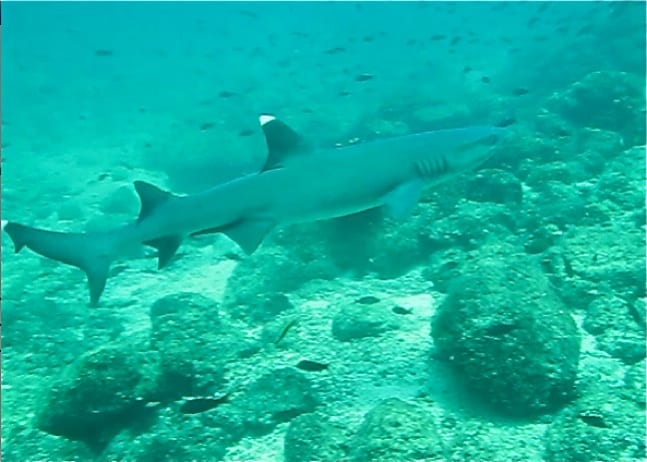

We were underwater perhaps 45 minutes, but the time seemed to fly by. In addition to the myriad unidentified fish species, we also saw several different types of Puffers (including several vivid yellow ones) and Eels. But the best sighting by far came when we rounded a corner and stumbled onto a trio of Whitetip Reef Sharks, each about 5 feet in length. I’m not sure who was more surprised to see whom, but– as we’d experienced in the Galapagos Islands– they were quick to beat a hasty retreat immediately upon spotting us.

Eventually it was time to leave the water and have lunch before making our way to the Coiba Island Penal Colony. There was a palpable shift in mood from the moment we stepped onto the beach, with not a single other tourist in site. For native Panamanians, the name Coiba does not evoke images of a tranquil, uncrowded nature reserve, but a hellish nightmare along the lines of Devil’s Island or Alcatraz. Even the brilliant midday sun could not fully illuminate the dark shadows this place reflected from the nation’s difficult political past.

Like many prisons, the Coiba penal colony was once home to some of the nation’s most dangerous criminals. But being imprisoned there indefinitely was also the response to anyone who dared to question the harsh brutality of Noriega and Torrijos’ regimes. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of political prisoners (known as “Los Desaparecidos”) were housed here, with 30 camps spread across the island during its peak.

“Haunting” is perhaps the best word to describe the feeling of exploring the prison ruins. Vivid imagery of pain, misery and torture was impossible to banish from our minds as we explored the ruins of the prison cells and the tiny Catholic Church where hundreds of men, ripped away from their friends and families, must have come to pray to God for mercy upon their souls. Even in broad daylight, the spectre of dark misdeeds hung heavy over the place.

There’s no formal museum yet, but the prison grounds did have a hut featuring a detailed map, a bit of history, and a handful of relics found in the ruins of the penal colony. These crudely crafted shanks offered a reminder that the guards weren’t the only malicious men the political prisoners had to watch out for.

High on a hill overlooking the beautiful blue waters of the Pacific, we found the unmarked graves where many of the Coiba Island Penal Colony’s dead were buried. They were the lucky ones: Those who tried to escape were frequently dismembered and fed to the sharks who populate those waters.

We probably spent less than 90 minutes exploring the ruins of the penal colony, but we were truly glad when it was time to leave. It’s not exactly what you’d call pleasant being forced to reconcile yourself with the evils that men are capable of in their quest for power and wealth, but it made us thankful that Panama had toppled Noriega’s regime and emerged as the burgeoning ecotourism hotspot it is today. Where once Coiba was associated with torture and tragedy, now nature is gradually reclaiming the land, turning the island into a national park truly worthy of must-see status. –by Bret Love; photos by Bret Love & Mary Gabbett except where otherwise noted