The Garifuna Collective

Preserves the Rich Culture of Belize

The Garifuna culture of Belize has been a fascination of mine for over a decade now: It’s one of my primary reasons for ranking the country so highly on my “Dream Trips” wish list. Located south of Belize City near Dandriga, the small fishing community of Hopkins Village has preserved this remarkably rich culture for hundreds of years.

The Garinagu people, whose language and culture is called Garifuna, descend from shipwrecked Africans whose ancestry can be traced back to the Yoruba, Ibo, and Ashanti tribes of Ghana, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone. After making their way to Central America, they intermarried with Carib and Arawak Amerindians, and came to be known by the British as “Black Caribs.” Their music, dance, food and clothing offers a mixture of African, Amerindian and Spanish influences that is unique to Central America.

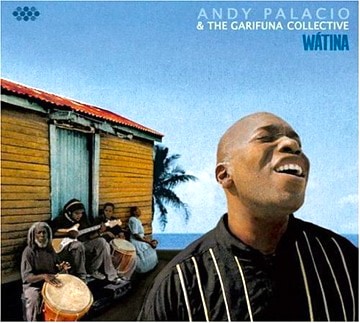

Proclaimed a “Masterpiece of the Oral & Intangible Heritage of Humanity” by UNESCO in 2001, Garifuna culture went unknown outside the region until 2007, when Andy Palacio & the Garifuna Collective released Wátina. The album, which earned favorable comparisons to Paul Simon’s Graceland, put the culture of Belize on the map, eventually earning the title of Best World Music Album of All Time by Amazon.

Unfortunately, Palacio– a prominent Belizean cultural ambassador and outspoken advocate for the preservation of Garifuna culture– died from a stroke at the untimely age of 48, just months before the band’s scheduled world tour. The loss was devastating to Belize, but even moreso to Ivan Duran, who produced Watina and released all of Andy’s albums on his Stonetree Records label. It was Duran who was left to pick up the pieces after Palacio’s passing. Now, five years later, he and The Garifuna Collective are back with two new albums.

I was recently honored to get a chance to speak with Duran about Garifuna music, Andy’s death, and the rich cultural traditions of Belize.

How would you describe the Garifuna culture of Belize for people who don’t know it?

It’s unique because it’s a blend of West African traditions with indigenous Caribbean traditions. It’s predominately an Arawak language, but it has many words that come from Africa, English, Spanish and French. But perhaps the most interesting aspect is the music. Garifuna music is a rich blend of African-derived rhythms mixed with soulful melodies, which are predominately from Arawak and Carib Indians. It’s very unique in the world.

Can you talk about Punta and Paranda? What makes them unique among Caribbean music forms?

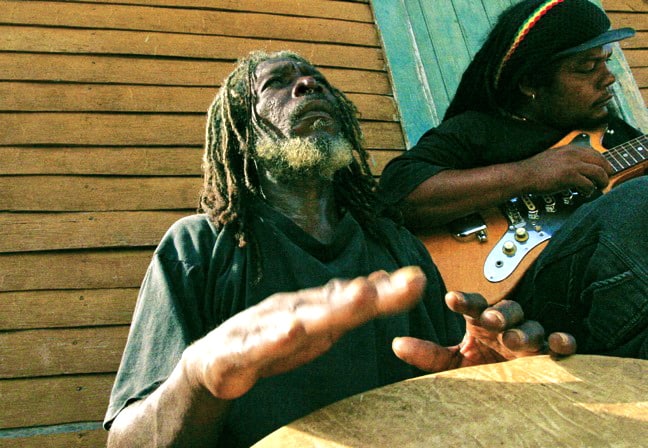

In Garifuna culture, Punta and Paranda are the most popular rhythms. They’re very different. Punta is fast and danceable: It’s a fertility dance, so it’s a very sensual movement between a man and woman. It’s sung in a West African call-and-response form, with pulsating drums. Paranda is the more soulful side of Garifuna music, composed on guitar. They’re much more melodic, and there’s a bit of Latin flavor to the rhythm. The guitar was introduced when the Garifuna were exiled to Spanish colonies in Central America, and they assimilated it into the culture. It sounds very romantic, but it’s also about storytelling. Each town would have a couple of Parandaros, who’d write songs for the village. The songs would range from a love story to a tragedy, like a hurricane or someone’s house burnt down.

So they’re like the griots of West Africa?

Yes, absolutely! The songs of the village traveled to other villages, and were adapted. Some songs from Honduras ended up in Belize, and vice versa. They exist in both countries, but they’re completely different.

How did the Garifuna Collective originally come together?

It started in the mid ‘90s, when I launched Stonetree Records. I kept working with the same musicians and composers, so it became obvious that we had chemistry. When we started recording Wátina with Andy and the rest of the guys, we had to decide what to we call it. That’s when we came up with “The Garifuna Collective.” It was the most accurate way to name the band, because it was a collective effort. Everyone contributed to the songs. When Wátina was received well, Andy took the bull by the horns, and we were very lucky for that. He was by far the biggest contributor, and also the most eloquent and charismatic.

How did Andy’s untimely passing affect you and the group?

Losing Andy was a huge blow, both professionally and personally. Our whole world was shattered. Belize became a different country the next day. It felt like we lost part of ourselves. There was a tour scheduled to happen after he died– a tour that had been booked many months in advance. The first thing we had to decide was whether we were going to cancel it. Everybody said, “Absolutely not! We’re going to make it the Andy Palacio Tribute tour,” which became our biggest tour ever. Andy opened up the doors for us, and there was no way we were going to let that door shut in our faces. We needed to make sure we left at least a crack open: If the world were to forget what happened, it would be extremely difficult for the next generation of Garifuna artists to take advantage of what Andy had accomplished.

Amazon named Wátina “Best World Music Album of All Time.” Do you feel like the album’s success opened the world up to the culture of Belize?

I take awards and lists with a grain of salt. But I can understand why there was all the publicity and willingness to acknowledge the work. Central America has never been known for positive things. When you think of the region, you think about civil wars, hurricanes, and the drug trade. You don’t think about great music. Wátina is an extremely inspiring story when you think of it in a historical perspective. In the time of St. Vincent, the Garifuna were all exiled and left on an island to die of disease and hunger. Now, not only is Garifuna culture surviving, but they’re showing the world that celebrating these traditions actually pays off. It’s remarkable what’s been accomplished with a few dedicated people.

The new album’s title, Ayó, means “goodbye” in the Garifuna language. Is that a tribute to Andy?

Absolutely. We’re paying our respects and wishing him farewell. Also, to the world, we’re saying that we won’t be stuck in the past. It took us 5 years to finish this album. One of the biggest accomplishments of this record, at least for me, is that now it sounds like a band. We’ve found our sound. One of the decisions we had to make is that we’ll never have a frontman again. That’s Andy’s spot, and he will never be replaced. We’re kind of like The Wailers without Bob Marley. In order to do that, we had to learn, grow and transform. Now, it feels like the whole village is singing. That’s beautiful, because it’s a true reflection of what music means in the Garifuna community and how songs are made. It’s always a collective effort.

What’s your dream for the future of the Garifuna Collective?

This album gives me confidence that we have a very unique sound. Whether you like it or not is another question. My dream is that we infect other artists with our musical vibe. I think Belize’s contribution to the music world is that we can apply what we do to almost any style of music and make it better. From the way we record albums, to the instruments we use, to the way we create and arrange music, it’s totally unique. I hope that Belize can become a major tourist destination in the future, just like Jamaica was after Bob Marley. I think Belize is an ideal place, and I think we have all of the elements for that to happen. –by Bret Love; all photos provided by Cumbancha/ Stonetree Records

If you enjoyed reading about the Garifuna Collective & the Culture of Belize, you might also like:

INTERVIEW: Bob Marley’s Legendary Wailers

INTERVIEW: Sierra Leone’s Refugee All-Stars

INTERVIEW: Tuareg Guitarist Bombino

INTERVIEW: Musician Baba Salah On al-Qaeda’s Invasion of Mali