THE CLIMATE CRISIS

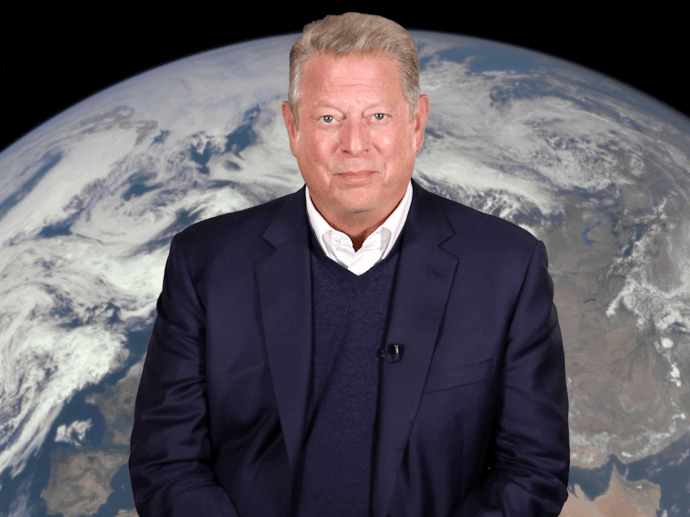

Former VP Al Gore Spreads the Gospel of Global Warming on a Grassroots Level

It’s pretty shocking when you find out you’re about to interview the former Vice President of the United States. I first met Al Gore during his whirlwind world tour to promote his documentary film, An Inconvenient Truth, in which he spelled out in layman’s terms the details of a global climate crisis that could prove far more devastating to the planet’s future than any terrorist ever could.

Shot on a slideshow tour that found him taking his message from city to city like a modern-day Johnny Appleseed, the film revealed a side of Al Gore rarely seen during the historic, controversial 2000 Presidential campaign.

Relaxed, animated, downright passionate, Gore now seems rejuvenated by his belief in his mission to save the world, exhibiting the same sort of affable accessibility that made guys like Bill Clinton and Barack Obama so damn popular while discussing everything from his professional failures to his personal passions with refreshing humor and easygoing charm.

The origins of “An Inconvenient Truth” obviously began with the loss of the 2000 election, since you wouldn’t have time for your slideshow tour if you were President. How did that loss affect you, not just in your political career but also personally?

Well, the deeper roots of it began when I was in college in the 1960s and was given some of the first information ever gathered about this problem that has become a planetary emergency. Since that time, at every stage of my life when I have reassessed my priorities, this has come to the surface.

After the election of 2000, when I once again made a fresh start and reassessed my own personal and professional priorities, this became my top priority. Since I didn’t have a job (laughs), I focused even more on it. I’m sorta joking—I had a job teaching and started a couple of businesses—but I did have an opportunity to start with a blank slate, which didn’t seem like a great thing under the circumstances.

But it had some good things about it because I was able to dig in and start delivering the message about the climate crisis in a new and ultimately more effective way. I started giving my slideshow all over the country and all over the world, and that led to some movie producers seeing a showing in L.A. and having the idea of making a movie out of it. I’m glad I listened, because they’ve done a great job.

At what point did you realize that global warming and its environmental effects were something America drastically needed to address?

It came in several waves. The first event was being shown the first evidence of what was happening with CO2 in the atmosphere and having it interpreted by a scientist who was such a hero to me, then watching all of his predictions come true over the years.

When I had the opportunity in the ’70s to be a member of Congress and have hearings on whatever issues I wanted, this bubbled to the surface as one of the most important issues, and I started attacking it as a public official.

When I went to the Senate I dug in more deeply, and after my son had his accident—which shook me up and caused me to reevaluate all my priorities—this was the professional priority that rose to the top. I started giving my slideshow and wrote my first book, “Earth in the Balance.”

But it was after the 2000 election that I decided I had to go on the road with this and take it everywhere, and go door to door if I have to and try to convince people to take action. It’s like if you were on the beach and found a message in a bottle sent to a specific address, and the message said, “Whoever finds this, please deliver it because it’s a matter of life and death,” you’d feel obligated to do what you could to deliver that message! It’s the same thing with me in this situation: The message is a matter of life and death for our civilization, and the address is the American people.

There was so much criticism of you as “wooden” during the 2000 election, but in person you seem quite passionate. Do you think our political system makes it difficult for a candidate to get a message like this across over the course of a campaign?

Yeah, I think it does. I’ve learned more about a lot of things, and the old cliché is that whatever doesn’t kill ya makes ya stronger.

But I do think that the modern-day American political process discourages the passionate discussion of large ideas that embody inconvenient truths that people don’t necessarily want to hear about.

The political process instead rewards homogeneity and messages that can be boiled down to 27-second TV commercials. I sometimes wonder what the founding fathers would’ve done if they had to discuss their ideas back in 1789 in 27-second soundbytes. I doubt we’d have a country!

How hard was it to sit on the sidelines and watch as the Bush administration encouraged things such as drilling for oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and fracking for natural gas in middle America?

At times that was very difficult. Even though I’m a recovering politician (laughs), I get to the point every now and again where I just can’t take it anymore, so I give a stem-winder of a speech and just unburden myself.

I do that as a private citizen in what I think is one of the best traditions of our country. I do believe, along with James Madison, that a well-informed citizenry is the bedrock of our American system. But one of the main reasons I do that is because I get to the point where I just can’t stand it anymore! (Laughs) And that feeling comes much more frequently than I give a speech, by the way.

The company behind your film (eBay magnate Jeff Skoll’s Participant Media) also co-financed Syriana, which dealt with the ways our reliance on fossil fuels is tied into America’s political presence in the Middle East. Can you about how our unquenchable thirst for oil feeds into the devastating effects on the environment you discussed in “An Inconvenient Truth”?

Well, look at the pattern. We go deeply into debt to China and borrow money that we use to buy enormous sums of oil from countries in the most unstable part of the world, where we have to send troops, partly to secure the supply lines. Then we bring all that oil back here and burn it in ways that destroy the livability of the planet.

This is not a good pattern, and we need to break it. We have a debt crisis, an energy crisis and a planetary emergency that are all linked together. We need to grow cellulosic ethanol. We need conservation. We need hybrids. We need a new generation of technology that allows us to use energy FAR more efficiently.

We need to shift our whole economy to a more granular approach to energy and natural materials so that we don’t waste more than 90% of what we think we’re using so that we save money and improve the quality of life and protect the environment all at the same time.

Why do you think the government and American auto manufacturers are so resistant to the idea of renewable resources?

Well, sometimes the old saying is true that our strength can become our weakness. We built the most powerful, most profitable automotive industry on Earth, and we did it by following a particular formula that Henry Ford innovated.

Breaking out of that formula is sometimes more difficult for an industry that has been successful at the old way than it is for a newer upstart like Toyota, for example, who stole the leadership on environmentally-friendly cars and the leadership as the biggest auto-maker on the planet.

But no matter how much advertising they pumped into SUVs, people don’t want to buy them now because they’re going to the gas station and having to take a mortgage out just to pay for a tank-full! (Laughs)

What do you think it will take to convince the average Joe to take the climate change issue seriously, and to take action towards resolving it?

Redefining it as not a political issue, but a moral issue. There are precious few exceptions, but most everybody, when confronted with what they see as a choice between right and wrong, will try to choose right.

This issue– because it affects the survivability of human civilization; the inhabitability of this planet; and the welfare of not only our grandchildren, not only our children, but of US—is a moral issue.

And when people see it framed accurately in that way, they will, and they are, choosing the right course of action. –Bret Love

If you enjoyed reading our Al Gore Interview, you might also like:

Ted Turner on Alternative Energy

Sustainable Living Expert Laura Turner Seydel