South African Music Legend Johnny Clegg

On Apartheid, Nelson Mandela & His Nation’s Future

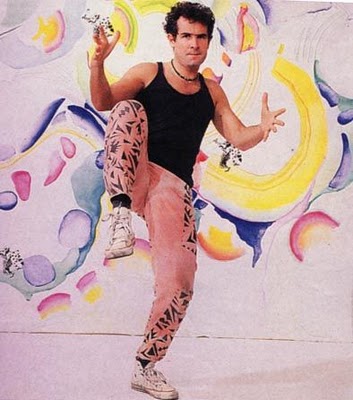

Born in England, but raised in South Africa, Zambia and Zimbabwe, Johnny Clegg emerged as a revolutionary musical force in the ‘70s and ‘80s by combining African and European lyrics and musical influences that spoke out against government oppression at the height of Apartheid.

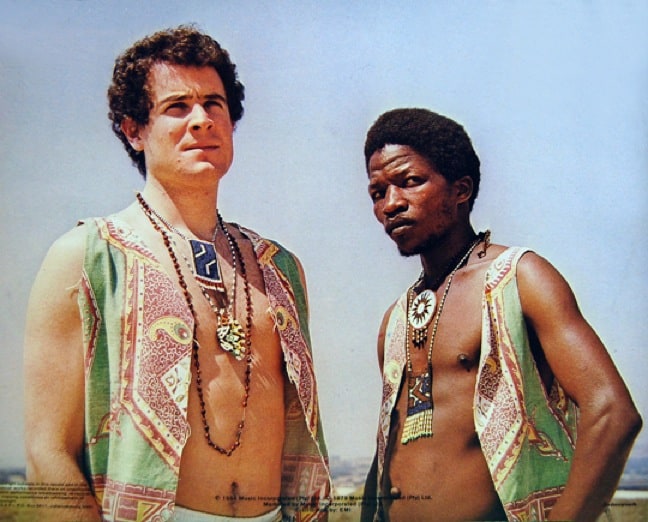

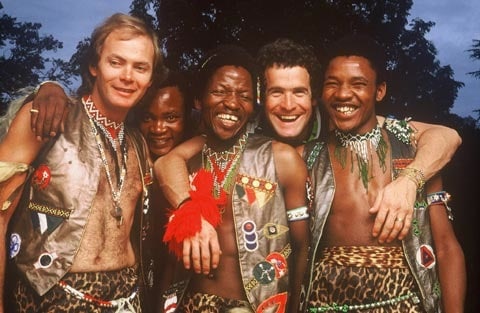

Known as “The White Zulu,” Clegg started his first racially mixed band, Juluka, in 1969 after falling in love with Zulu culture and musical traditions. The mere act of playing with Zulu musicians such as Sipho Mchunu was illegal at the time, and explicitly political songs inspired by South African trade union slogans didn’t earn the band any fans in the Apartheid regime. Clegg and his bandmates were arrested repeatedly.

When Mchunu left Juluka in 1986 to tend his family’s cattle, Clegg formed Savuka, whose Zulu name means “we have awakened.” Clegg, who by this point was teaching Anthropology at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, became increasingly political on 1987’s Third World Child. The song “Asimbonanga” became a rallying cry for the anti-Apartheid movement, calling for the release of Nelson Mandela and canonizing 3 martyrs of the liberation struggle– Steve Biko, Victoria Mxenge and Neil Aggett.

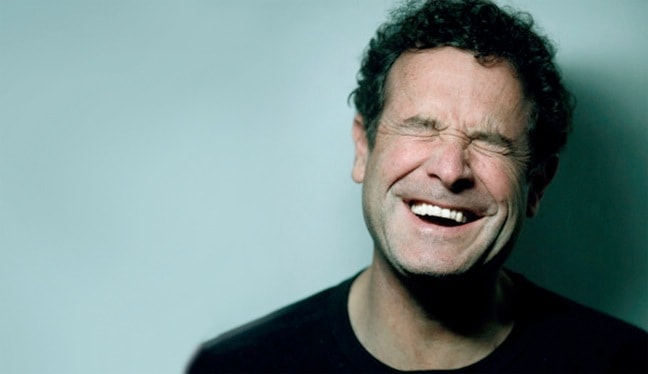

By the late ‘80s, Clegg was as popular in Europe as Michael Jackson. In 2012, he received the South African Presidential Ikhamanga Award, the highest honor a citizen can receive there. And when Nelson Mandela passed away earlier this year, “Asimbonanga” was the emotional anthem sang in the late leader’s honor.

Clegg is currently in the midst of his largest North American tour to date in support of his new album, Best, Live & Unplugged. A visit to South Africa back in 2000 changed my life, so I was truly honored to get a chance to speak with the musical legend about life during Apartheid, his fascination with Zulu culture, what made Nelson Mandela so beloved, and his hopes for the future of his homeland.

What were your early impressions of life in South Africa?

My mother was a jazz singer and married a South African reporter, so we moved to Johannesburg when I was 7. South Africa being what it was, we lived in a white area and there were black areas and Indian areas. When I was 8, my stepfather took me into the Townships, where he taught black kids how to play drums.

When I was 9 old, we immigrated to Zambia– a democratic, non-racial country. I went from a whites-only school to an integrated school where there were more blacks than whites. Zambia was a golden time for me. Then we came back to South Africa, and I was back in a whites-only school.

When I was 14, I met a street guitarist [Sipho Mchunu] around the corner from where I lived who was playing Zulu music on the guitar. That was the moment that the universe opened up for me.

What was it about Zulu culture that spoke to you?

The Zulu have a very strong tradition of warrior values, such as being tenacious, stubborn and determined. If you’re confronted by a situation, you attack it from all angles until you get around it, over it or through it.

They took guitar, violin and other instruments and reconfigured them in innovative ways. They changed the tuning, changed the strings, bridged them with wooden capers so that some strings would be free and others would be held down… it’s a take-over of these western instruments that you can play African music on. I found it fascinating!

Playing the music opens up other cultural aspects– the way the language operates, the melodies, the rhythms of the war chants, and group expression of their identity.

What it was like being a progressive white man during Apartheid, actively calling the oppressive government out in your music?

I was arrested for the first time when I was 15, and then arrested multiple times for trespassing on municipal property. All these minor infractions started to build up resentment in me. Apartheid was like seeing a fence arbitrarily put across the road. I just had to find my way around it.

Until age 18, I was so involved in becoming a Zulu that the trade-off of being arrested was worth it. I thought it was cool, because my Zulu friends were going through it on a daily basis. It was part of the community experience, and a rite of passage for me as a young man. I didn’t think of it from a political perspective until I went to university and studied politics and anthropology.

I started to understand the fundamental questions: Why is there a fence, and who put it there? Then I became involved in the trade union, early wages commission, etc. I got arrested for my political actions, not musical actions. Basically, I fell in love with a culture and found ways to get in there, and then later I got very politically active.

When did you first realize that Apartheid’s days were numbered?

1986 was the pivotal year when the Liberation movement decided to make South Africa ungovernable. They took over the Townships, and the government declared a State of Emergency. There was a feeling that we were reaching a crescendo, and something was going to happen. Either we were going to slip into a terrible civil war, or there was going to be a negotiated settlement.

The four years after Mandela was released– from the 11th of February 1990 until 1994– were really touch-and-go. All of the boycotts, both outside and the consumer boycotts inside South Africa, were apart of a multilayered strategy to isolate the Apartheid government and bring them to their knees.

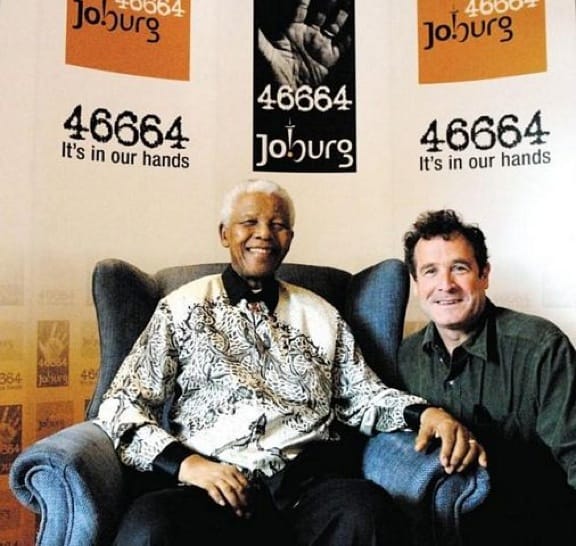

What, in your opinion, made Mandela such a beacon of hope for South Africa?

For someone who had been through what he’d been through, he had a well-developed sense of humor. He was also a very good listener. He read you. He had social radar, and a communication ability of note. He was careful and deliberate in his response to questions. You always had that sense that he had given it quite some consideration.

He could also be quite grumpy. I remember at a big National Executive meeting, people in the audience were chanting something against one of his positions. He waited until it died down and said, “You have voted for me based on the policies that we put out. I have been elected as the leader. Let me lead!” He had opinions, but was never opinionated. He knew he was the bridge between all of the various factions, both within his party and within South Africa, and his main aim was to be a nation-builder.

He let all the other stuff– poverty alleviation, job creation, and housing– be done by his advisors. He was more interested in establishing a sense that everyone had a place in the new South Africa. He even had tea with the wife of the architect of Apartheid. He knew that he had to create a sense of inclusivity. The other thing I think he will always be remembered for is a very deep well of forgiveness.

What are your hopes for the future of South Africa?

South Africa has three unique problems.

First off, we have to deal with the legacy of Apartheid. There are geographically separated townships which were created as pools of labor for white cities. Today, the labor force doesn’t live in the city where it works, and has to spend $2-$3 per day on transport. If you look at the railway lines that run throughout the country, they went through the areas where the white farms were. The infrastructure of the country is completely representational of the Apartheid policy. We have to find a way to break down those legacies and create more accessibility.

The second thing is that we are a country of first and third world makeup. We have traditional, tribal, rural cultures and economies; and we also have very modern, western-developed, urban communities whose children don’t speak a traditional African language. There has to be a road map to enable a conversation between these two groups so that we can move forward together.

The third, and biggest, problem is that, while we are doing this, we also have to enter the global economy at a competitive level. We have to finds ways to make our world attractive to investors.

I really fell in love with South Africa when I first visited 14 years ago. What makes it such a special place for you?

In 2009, I was engaged by the South Africa Broadcasting Corporation to do a travel program prior to the 2010 World Cup. We went to all nine provinces and spent 10 days there, looking at landscapes, the communities in those landscapes, and the art they create. It was the most amazing experience.

South Africa has a diverse ecological and geographical make-up, from savannah grasslands, to tropical and sub-tropical forests, to deserts and semi-deserts. There are areas along the Garden Route which are National Heritage Sites simply because there are flowers and vegetation there not found anywhere else in the world.

It’s a place where you discover yourself, because the landscape is so big that you have to reconsider your own position in the universe. It’s such a culturally diverse country that you can travel through any of the provinces and meet different groups of people– urban, rural, tribal, modern, all speaking different languages and having traditional music and dances. It’s a fantastic country to spend time in. –by Bret Love; all photos provided by Johnny Clegg

If you enjoyed our interview with Johnny Clegg, you might also like:

INTERVIEW: Ladysmith Black Mambazo

INTERVIEW: Soweto Gospel Choir

SOUTH AFRICA: Londolozi Game Reserve Safari

SOUTH AFRICA: Phinda Game Reserve Safari

SOUTH AFRICA: Zulu Memories