From Allen Ginsberg and Arthur Miller to Jon Krakauer and Stephen King, I’ve had the chance to interview some seriously influential authors over the course of my career.

But never have I interviewed one as divisive as Salman Rushdie. The award-winning author recently granted us a 1-on-1 interview to promote the new Midnight’s Children movie, an artful adaptation (from Oscar-nominated director Deepa Mehta) of his breakthrough novel.

Born Ahmed Salman Rushdie in Bombay, India in 1947 into a Muslim family of Kashmiri descent, he started his career as an ad copywriter.

He became a full-time author after his second novel, Midnight’s Children, won the Booker Prize for its unique combination of historical fiction and magical realism.

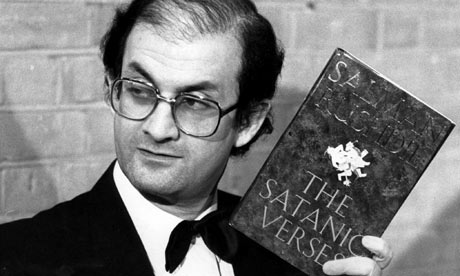

Of course, Rushdie ultimately became best known for his 1988 novel, The Satanic Verses. The book sparked violent protests from Muslims, who were incensed by the creative license the author took in his novel, which was based on the life of the prophet Muhammad.

Outraged by blasphemy and a perceived mocking of the Muslim faith, a fatwā calling for Rushdie’s death was issued by Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in 1989.

For well over a decade now, Rushdie has lived in the United States, serving since 2007 as Emory University’s Distinguished Writer in Residence in our hometown of Atlanta.

He’s been busy writing, working on a sci-fi series for Showtime (which he told me may or may not come to fruition) and releasing Joseph Anton: A Memoir, which details his life during the Satanic Verses fatwā. He also wrote and executive produced the Midnight’s Children movie.

The semi-autobiographical story, which was loosely based on Rushdie’s childhood, deals with India’s struggle for independence from British colonial rule. It also touches on the extremely bloody partition of the nation, which created Pakistan.

We were delighted to sit down with the knighted author to discuss the new film adaptation, India’s independence, and the lasting impact the end of the colonial era had on his homeland.

This seems like a very personal project for you.

With Midnight’s Children, I wanted to write a novel that arose out of that place (Bombay) at that time, using my own experience.

I gave Saleem certain parts of my childhood, so essentially he lives in my house and goes to my school.

His friends are composites of people I went to school with. The school bullies know who they are.

What are your strongest memories of growing up in the time of India’s struggle for independence?

Looking back at my childhood, I felt it was an extraordinary period in the country. It was the end of the [British] empire and the beginning of independence.

This was the first generation of free children to be born in India in more than two centuries! Transition is an interesting and confused time: The past is still there, but the future is being born.

Bombay has always felt a little different from the rest of India, in the way that New York doesn’t feel like the rest of America, and Paris is not like the rest of France.

One of the great characteristics in Bombay at that time was tolerance: There was virtually no sectarian trouble. We didn’t care about the Hindu-Muslim conflicts that happened in other places.

The families I grew up with in my little neighborhood were of every conceivable background– European, American, and Indian, Hindu, Muslim, Christian, Farsi, Sikh, Buddhist, etc. I wanted to write the book out of that spirit.

Can you talk about the impact of Colonialism in India, and how the withdrawal of those influences impacted the nation?

After World War I, Britain was impoverished by the war effort. There was actually food aid going from America to Britain.

With the election of their first Labor government, the British suddenly decided they couldn’t afford [the price of Colonialism]. Suddenly, the India Nationalist Movement discovered the British resistance against them was collapsing.

When it was done, it happened at an almost indecent speed. When the British finally sent their last Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, he arrived with instructions to get out as fast as you can. They set the date for Indian independence 10 weeks later.

After 250 years of Colonialism, you had to do the whole process in 10 weeks.

Ten weeks? That’s incredible…

Yes. To withdraw the entire power structure in 10 weeks and, at the same time, divide the country into two countries, created endless chaos.

There’s no doubt that the violence that happened is partly the product of that. What was awful was that this moment that should’ve been of great hope turned extraordinarily bloody, with these huge massacres.

The official number [of deaths] could be 300,000-400,000 people, but most informed people say it may have been double that, or close to a million people who were slaughtered, both Hindu and Muslim, in the partition riots.

So you have this country born with this double-edged thing– great hope and incredible carnage. You have to look at both things to see how the country would develop.

The idea of the “Midnight’s Children” was, yes, it was about my generation, but I also wanted them to embody the possibility. The idea behind giving them magic powers if they were born in the midnight hour was to say, “Freedom is a magical moment, and here is the potential of that freedom.”

What were you trying to say about the impact of Colonialism on Indian culture?

The British believed they were doing good– they called it “hundreds of years of decent government”– but clearly they did harm.

When we showed the film to younger audiences in India, the events surrounding India’s independence felt like ancient history.

But as the film gradually moved towards present events, particularly the Emergency of 1975-1977 (when PM Indira Gandhi suspended elections and civil liberties), they felt more connected.

Right now in India, there’s a big conversation about political corruption and the rise of authoritarianism in various Indian states. So they could easily relate those scenes to what’s happening outside the theater today.

Do you think there were any positive impacts of the Colonial era?

To give the British their due, they built the railroads and roads, and left behind an extremely efficient civil service center, without which India couldn’t function. They wrote a constitution totally lacking in religion, which has been a very valuable thing.

After India’s struggle; for independence, the British left the country in pretty good shape structurally. But it was a mess in terms of the calamities that were happening.

As with America, the founding fathers of the Indian Independence Movement were great men who were available to lead the country into the moment of freedom. India was very blessed by those leaders– people of deep intelligence, deep philosophy, great sophistication and selflessness.

It was clear to them, because of the partition massacres, that the question was, how do you make sure that never happens again? The answer was that you have to keep religion out of the state.

India has a gigantic religious majority, with 85% of the population that is in some way Hindu, then you have 12% Muslim, and 3% Buddhist, Christians, Jews, etc. They felt that if you have a religious state, the big majority would dominate the minorities, and that would create stress.

Now, a much smaller-minded generation of Indian politicians is trying to impose a majoritarian culture on India, which would lead to the exact kind of discord that the Founding Fathers were trying to avoid.

At the moment of independence/de-colonization, India was lucky in being left with a constitution that was sensible, and blessed with leaders who knew how to defend and protect secularism.

In closing, I wanted to talk about the controversy that has surrounded you ever since the release of The Satanic Verses. I’ve read that you had to be surreptitious when filming in certain locations for the Midnight’s Children movie, and that certain people in India spoke out against the film?

There were fears, including some nervousness about what would happen in India. This is a time in India when any two-bit politician looking for a headline can stand up and shake his fist to get some attention.

What’s interesting is that, at the Kerala Film Festival, there were one or two local politicians who did make a fuss. But overall the film went down very well at Kerala, and there was no attempt by the central government to intervene.

The film sailed through the censor board without a single cut. All these things that we had feared actually didn’t happen, and the filmed opened there without any trouble. –Bret Love

If you enjoyed our interview with Salman Rushdie on the Midnight’s Children Movie, you might also like:

On The Trail of Tigers in Ranthambore National Park, India

Indian Animals: A Guide to 40 Incredible Indian Wildlife Species

Anoushka Shankar On Indian Music & Her Famous Father

Indian Percussion Legend Zakir Hussain