I was only three years old when it happened, sending a cloud of radioactive material halfway across the world. It was the first nuclear accident of its kind. The world didn’t know how to react. This uncertainty was made worse by the fact that the Soviet Union (now Ukraine), where the Chernobyl Power Plant was located, didn’t disclose the full extent of the disaster.

I grew up in Italy. Yet I can vividly recall my mother frantically stocking up on canned food in the aftermath of the catastrophe. Like countless other Europeans, she feared that the radioactive fallout had contaminated the soil, worrying it would be years before we would be able to enjoy fresh produce again.

We lived thousands of miles away from the disaster zone. So I always wondered how life changed for those who lived in close proximity to the power plant. And what was the nuclear meltdown’s long-term impact on its environmental surroundings? In January I had the opportunity to visit Chernobyl and learn the answers for myself.

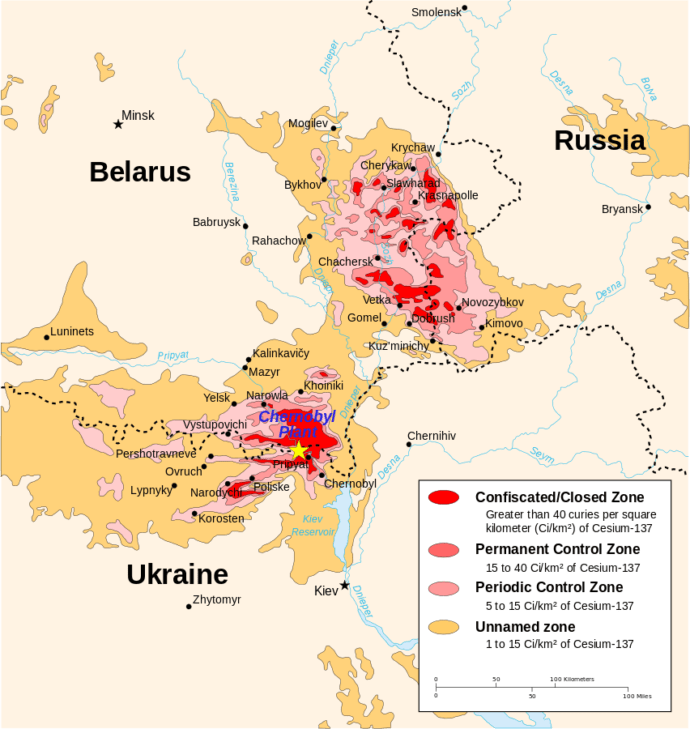

Radiation From Chernobyl Map (1996)

Table of Contents:

- Chernobyl Disaster Background

- Visiting Chernobyl Today

- Tour the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

- Wildlife In Chernobyl

- FAQS

Chernobyl Disaster Background

Early in the morning on April 26, 1986, a botched safety experiment sent Reactor 4 into meltdown. The fire that resulted from it released tons of radioactive material into the air. After a few days, the Soviet government evacuated the area within a 30km radius. In Chernobyl today, this area is known as the Exclusion Zone. See the red Chernobyl Exclusion Zone on the map above.

The power plant was located near two cities: Chernobyl (a formerly Jewish town with a millenary history) and Pripyat (a model town built in 1971 to accommodate the power plant’s workers). There were also several small villages nearby.

In total, over 200,000 people were resettled. They were told they’d only be gone for a limited time, so many fled with only the clothes on their backs.

The death toll of the Chernobyl disaster remains unknown. Only 100 or so people lost their lives as a direct consequence– some died in the explosion, while others perished from Acute Radiation Sickness a few days later.

But an estimated 600,000 people were exposed to dangerous radiation levels. So several thousand others died from cancer in later years, and cases of childhood thyroid cancer and leukemia rose considerably.

The immediate effects on nature were equally disastrous. Vast areas of forest were killed by the radioactive cloud, as well as small mammals and invertebrates. A coniferous forest near the power station turned bright red, earning it the nickname Chernobyl ‘s Red Forest. This area is still largely a no-go zone today, with radioactivity levels considerably higher than you’ll find elsewhere.

Visiting Chernobyl Today

The Exclusion Zone– an area as large as Luxembourg– remains largely uninhabited today. A cement sarcophagus was built around Reactor 4. In its core, where the meltdown occurred, there’s still a spill of radioactive material. It’s known locally as Chernobyl’s Elephant’s Foot, and it’s so toxic it can cause death after a mere five minutes of exposure.

The primary people living in Chernobyl today are the workers who are decommissioning the power plant (an effort that’s scheduled to end in 2065).

There are also about 100 samosely (self-settlers), former inhabitants of the Exclusion Zone who chose to return to their homes. The samosely are all elderly people living in their abandoned villages, while workers are stationed in Chernobyl town. Pripyat remains a ghost town.

Visiting the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone is safe now. Chernobyl visitors are encouraged to come in the Winter when it is the most safe.

Radiation is carried by dust and particles and accumulates in the ground, especially next to tree roots. This explains why radiation levels are at their highest in Chernobyl’s Red Forest. In Winter, snow covers the ground, minimizing contact with the contaminated soil.

It’s estimated that the levels of radioactive materials within the Exclusion Zone won’t dissipate for a further 20,000 years. That’s more than twice the length of humanity’s recorded history!

Tour the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone

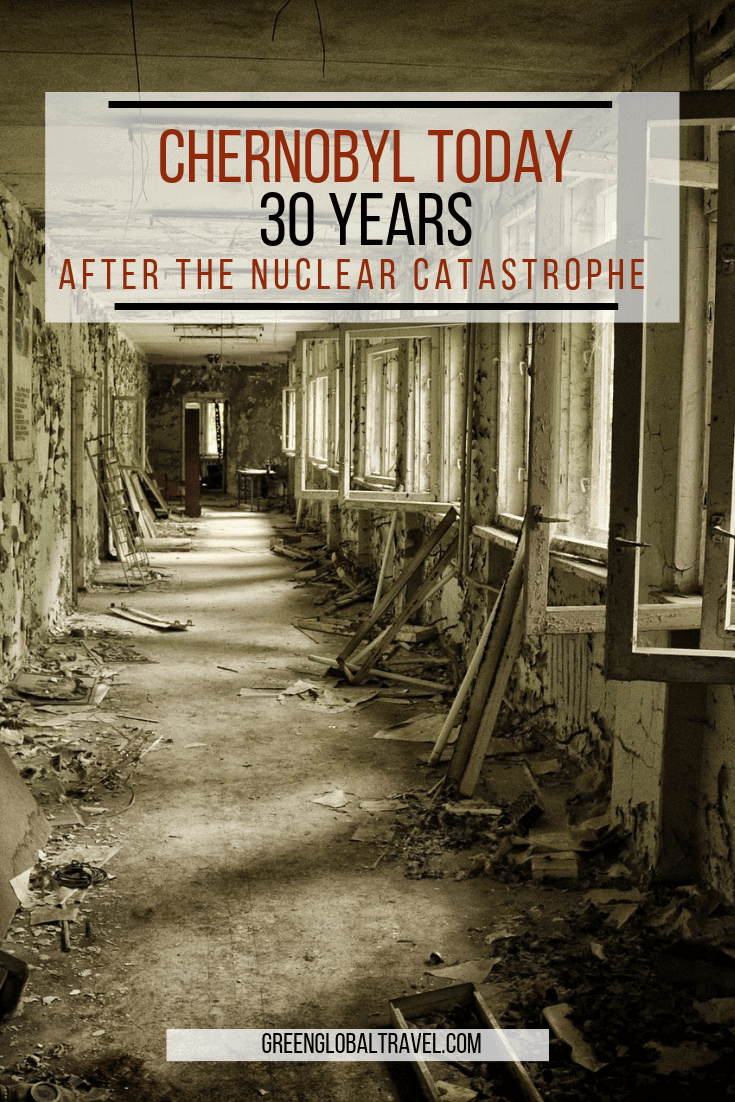

When I first heard about Chernobyl tours, I imagined the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone would look dead. I pictured the stereotypical post-nuclear apocalypse, with burnt-out patches on the ground, smoke rising from hollowed-out stumps, and a hazy sky.

I visited in the middle of the Winter, and it was admittedly hard to grasp. But if you visit in Summer, nature seems to be thriving in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Weeds grow between cracks on the pavement.

Tall trees almost hide the famous Pripyat ferris wheel from view. Bushes surround the huge, dilapidated Soviet squares.

After 30 years all but devoid of human presence, nature is reclaiming the Exclusion Zone. Somehow the no-go zone has turned into a thriving nature reserve.

When I say “nature,” I don’t just mean plants: Wildlife has also returned to the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone.

Starting in the late 1980s, aerial surveys carried out by Soviet scientists showed a consistent rise in the numbers of Wild Boar, Elk, and Deer.

Even when the overall numbers of Elk and Boar decreased sharply after the ’90s collapse of the USSR, numbers within the Exclusion Zone continued to rise.

Chernobyl wildlife has seen increases in populations of Beavers, Badgers, Lynx, and Bison that are far higher inside than outside the Exclusion Zone. The number of Wolves was recently estimated to be about 300– SEVEN TIMES higher than outside the zone!

There’s also been a steady rise in the number of small mammals and even Brown Bears recorded.

Wildlife In Chernobyl

Ever since this discovery was made, rumors of “radioactive Wolves” and other weird animals have spread. Recent footage of a Fox making a 5-layer sandwich after a TV crew gave it bread and meat led some people to believe radiation gave Chernobyl’s animals superpowers. Naturally, this was intended to be a joke. But what about the effect of radiation on Chernobyl wildlife?

Several scientific expeditions have been carried out, with conflicting findings. The results of an extensive survey led by Prof. Jim Smith of Portsmouth University and published in 2015 found no negative effect of radiation on Chernobyl wildlife.

Conversely, a joint French-American study published in 2013 claimed that negative effects due to radiation are widespread. They suggested that the Chernobyl disaster caused chromosome damage, higher mutation rates, health issues, and abnormal behaviors in a wide range of wildlife species. They say it even affected local Cuckoo calls!

Regardless, no one disputes the fact that Chernobyl wildlife numbers today are up. But, in the words of Prof. Smith, “This doesn’t mean that radiation is good for wildlife. Just that the effects of human habitation, including hunting, farming, and forestry, are a lot worse.”

And that reality– that nuclear disaster is not as bad for wildlife long-term than we humans– is definitely food for thought… –Margherita Ragg; photos by Nick Burns unless otherwise noted

FAQS

Where is Chernobyl?

Chernobyl is in Eastern Europe in the country of Ukraine 10 miles from the border of Belarus.

When did Chernobyl happen?

The accident at Chernobyl happened in the very early hours of April 26, 1986.

Can you visit Chernobyl?

Yes. Several Chernobyl tours are available.

Is it safe to visit Chernobyl today?

The safest time to travel to Chernobyl is in winter when snow is on the ground. Snow creates a barrier with the contaminated soil.

How radioactive is the Elephants Foot in Chernobyl?

Soon after the disaster in 1986, the amount of radioactivity in Chernobyl’s elephant foot was deadly after 30 seconds of exposure. Today, Chernobyl’s elephant foot’s radiation causes death after 300 seconds.

Are there people living in Chernobyl now?

Yes, approximately 100 elderly homeowners (know as samosely or self-settlers), have returned to their villages in the Exclusion Zone. The workers who are decommissioning the power plant live in the town.

If You Like it, Pin it!