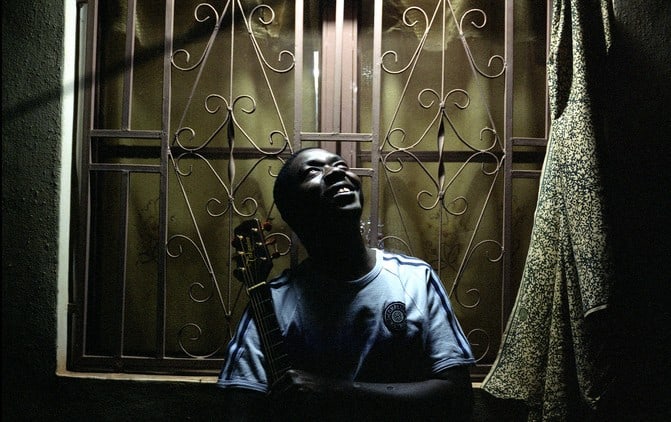

Musician Baba Salah On al-Qaeda’s Invasion of Mali

I’ve done over a thousand interviews in my 20 years as a journalist. But few affected me emotionally quite like my interview with Mali-based musician Baba Salah.

Though unknown in the U.S., Salah has been a star on the Bamako music scene since the mid- ‘90s, when he played guitar for legendary Malian diva Oumou Sangare. But now, with the release of his excellent new solo album, Dangay (The North), the “Jimi Hendrix of Africa” is emerging as a light of inspiration for the people of Mali in their darkest hour.

For a year now, the forces of al-Qaeda have been spreading like a virus throughout northern Mali. In a country where music is the very heart of the culture, they took instruments from people’s homes and burned them as an offense to Allah. They infiltrated Salah’s hometown of Gao, raped the women, killed and mutilated the men, and recruited children into their rebel army.

Though the French thankfully swooped in to help the Malian military beat back the al-Qaeda forces, nobody involved in the conflict seems to believe the battle is over for good. So when I spoke to Salah in mid-February, his concern for his country and his people was palpable. In this extensive, exclusive interview, we discussed everything from how al-Qaeda established such a strong foothold in Mali to his hopes for the future of his war-torn country.

In America, music is primarily regarded as popular entertainment. Could you talk about the importance music plays in the everyday lives of the Malian people?

Music is entertainment here as well, but also an important way for the population to get valuable information. In a culture that has a high literacy rate, people have many ways to get information. But in Mali, the society depends on artists to inform and educate. Life can be hard here, so music should allow people to dance, unwind and leave their problems behind. But at the same time, I am aware of my social responsibility. I am actually taking night classes in communication. I have a big audience in Mali, and to some degree internationally. So I can’t pass up this opportunity to pass on a clear positive message.

I’m fascinated by Mali’s Griot tradition. How would you describe the Griot’s role in Mali today?

The Griots are the guardians of history. In our culture, everything is oral. There isn’t a written language. A majority of the people here can’t read. So it’s the Griot who transmits the history from father to son, mother to daughter. That’s why in Africa we say, “When an old person dies, it’s like a library has burned down.”

When did you decide you wanted to be a musician?

I’ve always known. In Mali, traditionally only people who are born into certain families are musicians. I am not Griot caste– my family is noble caste– but music is my destiny. I have so many influences. Of course, people like Ali Farka Toure have had a great influence on all of us, and rock guitarists like Jimi Hendrix. But people like Jackson Brown have also influenced me. I knew about his music, and then he saw me play with Oumou Sangare in New York. After the show, he said he was really impressed by my playing. One day in Bamako I was practicing in my room, and there he was. He had flown all the way to Bamako to give me a guitar. It’s the same one I played on this album.

Mali has been in the news for the al-Qaeda activity there. What is the political situation that allowed them to gain such a strong foothold in the country?

The North of Mali is vast, and the borders are porous. Mali is a poor country, and we don’t have the means to secure this area. Most of the population considers themselves to be Malian, but there are separatist rebels in the North who want to secede. Many of them fought with Khadafy. When Khadafy fell, they returned to Mali, well armed. They joined the rebels and teamed up with foreign militants– Jihadists who are involved in trafficking. These are al-Qaeda (mostly from Algeria and Mauritania), and they have been operating in Mali for the last decade, moving cocaine and collecting hostage ransom from Europe. Together, they started to attack, and the Malian army suffered big losses. This led to a military coup in Bamako. During the chaos, the rebels and Jihadists advanced on the key northern cities and the Malian military fled.

Were you in Gao when the fighting broke out?

No. I was in the region doing concerts in December of 2012, and then played New Year’s Eve in Gao. After that, I left for Bamako. It was just after that that separatist rebels began attacking military outposts in Kidal. But we had an idea that this was coming. When Khadafy was killed, we knew the Tuareg that were in his army were coming to Mali, heavily armed. We knew what this would lead to.

One of the first things the militants did after invading was to destroy the musical instruments. Why do they see the music of Mali as such a threat?

Islam has been in Mali for centuries. The Islam we practice is older than the version the extremists want to impose on us. Timbuktu was an important center for Islamic scholarship. True Islam is moderate. It’s tolerant. As I said, in Mali, music is an important medium for communication. We are a poor country, but our culture is rich. It’s empowering. So taking away music is a form of control. They want us to forget who we are. But we’ll never forget.

Your album, Dangay (The North), is described as “an act of defiance against the very forces of intolerance that seek to destroy Mali.” Can you talk about the sociopolitical messages you wanted to convey?

In Dangay, I let the people who were suffering under occupation and terror know that the world had not forgotten about them, and that we would rescue them. I promised the Jihadists that we would sing and dance again in the North of Mali. I called on the politicians, the military, and all the religious leaders to come together for a solution. I called upon the international community to help. Women were being raped, people were being unjustly tried and then publicly mutilated. Their liberty and identity had been stripped from them. I had to say something. I also sing about children. We are constantly involving our children in our adult problems. Children are being forced into prostitution. In Gao, children were being recruited as soldiers. Childhood is sacred. If we want to have a peaceful future, we must protect the children.

How did the current turmoil in Mali play into your decision to release this album now? Did your work feel somehow more necessary in response to al-Qaeda’s actions?

When we started the album, we weren’t thinking all this would happen. Things unraveled quickly. But when I saw how my family and friends in Gao, and in all of Mali, were suffering, I was even more determined to finish the music and release it. Even before the coup and occupation, I was singing to give hope to my people. Mali is a poor country, and when the global economy suffers, we really suffer because so many people here live on the edge of survival. That’s what the song “Ay Derey” is about. I ask people to not give up. Rebellions aren’t new to Mali, and neither is ethnic tension, which is what “Amidininé” is about. We have worked though our differences before. I also sing to farmers, and ask our leaders to invest wisely in agriculture so it can be a motor for the economy. If the economy is strong and people have work and enough money to live on, there is no place for al-Qaeda here in Mali. If people are desperate, they can more easily be exploited by criminal elements.

What changes do you hope to see in your country in the future, to ensure the music and culture of Mali continues to thrive?

People need to have security. This is important. The North of Mali needs smart, sustainable development. For this, we will need good, honest leadership. People are going to have to change. We have a great past, but we can’t live in the past. We need initiative and innovation. That has to come from the people themselves. There is a lot of work to do. We need people who are willing to share ideas and knowledge. We need people who are working for Mali and for our children’s future… not just for themselves. –by Bret Love; special thanks to Brendan Van Son of Brendan’s Adventures

If you enjoyed reading our interview with Baba Saleh about al-Qaeda’s invasion of Mali, you might also like:

GLOBAL CULTURE: The West African Griot

GLOBAL CULTURE: Rock’s African Roots

INTERVIEW: Nigeria’s Seun Kuti

INTERVIEW: Senegal’s Baaba Maal

INTERVIEW: Sierra Leone Refugee All-Stars