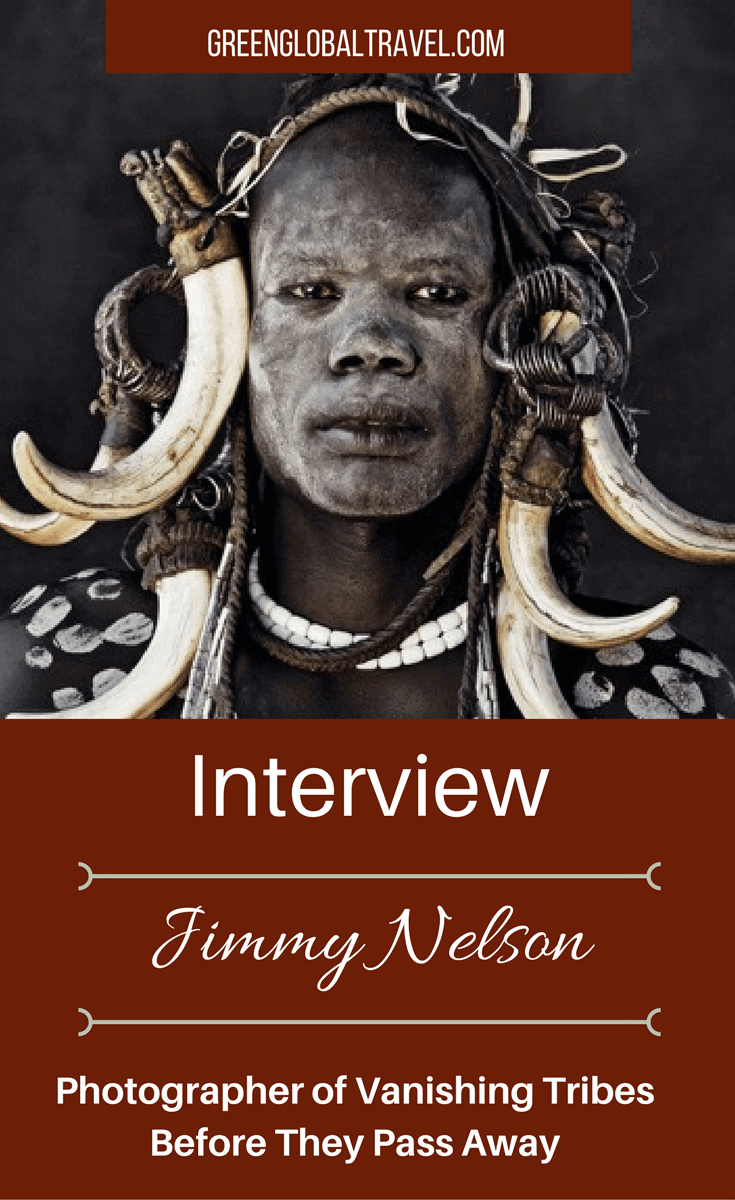

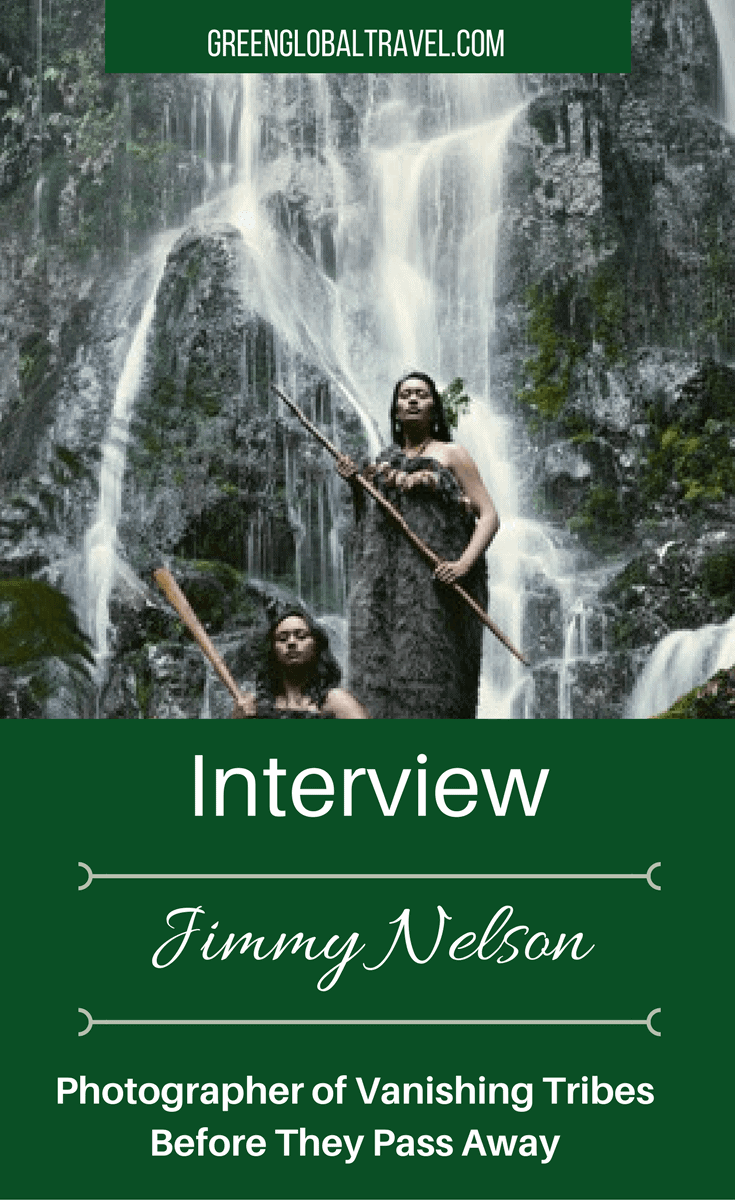

Jimmy Nelson Photographs Vanishing Tribes in

Before They Pass Away

I’ve been fascinated by tribal cultures for over 20 years, ever since I interviewed my grandfather about our family history and learned we had American Indian blood on both sides.

In the years since, I’ve traveled to indigenous communities in Dominica, South Africa, Tahiti, the Peruvian Amazon and numerous other destinations in an effort to learn from the tribal cultures there. So you can imagine how much photographer Jimmy Nelson‘s new book, Before They Pass Away, resonated with me on a personal level.

The project began in 2009, when the British photographer set out on a journey to visit and photograph 31 secluded, visually unique tribes. The quest would eventually take him (and his 4×5 large format camera) on 13 trips covering 44 countries. From the Huaorani tribe of the Ecuadorian Amazon to the Himba tribe of Namibia, from the island tribes of Vanuatu to the Chukotka of Siberia, Nelson’s extraordinary photos document ancient cultural traditions currently in danger of going the way of the dodo.

“I wanted to witness their time-honoured traditions, join in their rituals and discover how the rest of the world is threatening to change their way of life forever,” Nelson says. “Most importantly, I wanted to create an ambitious aesthetic photographic document that would stand the test of time. A body of work that would be an irreplaceable ethnographic record of a fast disappearing world.”

We were delighted that the intrepid traveler took some time out of his busy schedule to discuss the evolution of the Before They Pass Away project, his favorite memories from his journeys, and the importance of the cultural conservation message he’s ultimately trying to convey.

Let’s start off talking about the origins of this project. What inspired the concept?

Our world is changing at breakneck speed. Countries that were considered developing nations not so long ago are now among the world’s wealthiest. It’s inevitable that such rapid progress in affluence and technology ultimately reaches those cultures that, up until now, have managed to preserve their own identity and values. And when it does, their longstanding traditions will gradually disappear.

My dream had always been to preserve our world’s tribes through my photography. Not to stop change from happening– because I know I can’t– but to create a visual document that reminds us, and the generations after us, of the beauty of pure and honest living. And of all the important things it teaches us; ingredients we seem to have forgotten in our so-called civilized world.

I’m privileged to have had the opportunity to fulfill this life-long passion. But it is not about me: it is a catalyst for something far bigger.

I’ve been strongly influenced by tribal societies in my life and work as well. What do you think it is that fascinates us so much about cultures relatively untouched by modern society?

The main message of this project would be to look closer. We in the developed world are very comfortable with our prejudices and our judgments. Look closer, because you never know what’s around the corner. Some things can be very different than what they seem. We in the Modern world create all these barriers. When you are there with the tribes, it’s all about being human, not about what you can give or take from others.

I’m curious about the logistical details of putting a project of this scope together. How did you select the tribes you’d be photographing?

In this first phase of the project I researched the more remote and most aesthetically pleasing of tribes in order to obtain the attention of the world on this subject matter.

How did you go about establishing the trust required to get these remote tribes to pose for your “carefully orchestrated portraits”?

On a number of locations, when we first arrived somewhere, the people were reluctant to let us photograph them. What we did was to leave the camera behind for the first few days, in order not to intimidate them. We would sleep in their accommodation, because we did not want to give the impression that we felt we were better than them. Wherever we went, we always approached the people with enormous dignity. We tried to communicate, usually with the help of translators. When the people finally had warmed up to us, our enthusiasm worked as a catalyst for theirs. Our passion, our perfectionism, and our teamwork seemed to be contagious. And, in most cases, the locals soon wanted to participate in it. The positive energy and pride that emerged from working together with the people is reflected in the photographs.

Can you share a few colorful memories from your travels for Before They Pass Away?

There is one particular story of a tough moment for me as a photographer. There is a photo of three native Kazakh men from Mongolia with eagles on their shoulders on a mountain. That picture took three days to make, because each morning there wasn’t enough light.

On the fourth morning, it was about -20º on top of the mountain and the light was beautiful. I took off my gloves to take the photo and my fingers literally froze to the camera. I began crying, and when I turned my head I saw that two women had followed us to the top of the mountain. One of them took my fingers and cradled them in her jacket until I got the feeling back and was able to take a couple of photographs.

What I didn’t know was that these women are actually strict Sunni Muslims, and broke all their codes of modesty in order to aid me. They had noticed my desperation and did what they could to help me achieve what I was there for.

Any other favorite memories you’d care to share?

When I first met the Tsaatan people, they were a bit distant and refused to pose for the photographs. It wasn’t that they were unfriendly; they repeatedly offered me vodka, which, not being much of a drinker, I refused. But after failing to gain their trust in order to take their picture, I decided to put my camera away and play the grateful guest.

The result was that I got completely drunk and slumped into an alcoholic stupor. The next thing I knew, I was waking up in a teepee surrounded by 30 people, with a bladder fit to burst. Wrapped up in eight layers of clothes, with the temperature -40º outside, I didn’t see any other option but to pee in my pants and drift back off to sleep.

The next moment, I woke up in a tent that had collapsed under a stampede of reindeer, which are apparently attracted to the salt in urine. So there I was, standing in -40º with a reindeer licking my clothes. Well, that broke the ice! After making a complete plonker of myself and becoming the laughing stock of the group, they finally began to open up.

Were there any lessons you gleaned from these cultures that impacted you on a personal level?

If the tribes disappear, we will lose a living example of how to treasure our natural surroundings and values like hope, optimism, courage, solidarity and friendship. We could learn a lot from these authentic cultures that build on principal aspects of humanity, such as respect, love, survival and sharing.

We’re big believers in sustainable ecotourism as a way to generate revenue to fund conservation. Did any of these tribes have programs in place where travelers could visit them? Did they express any interest in getting to know outsiders?

The tribes I visited were remote and did not have any established tourism. But many did express interest in the outside world.

When you write that your dream was to “preserve our world’s tribes through photography” and “create a visual document reminding future generations of the beauty of pure and honest living,” it really spoke to me on a personal level. Do you have hope that these tribes will find a way to preserve their traditional way of life?

If we could start a global movement that documents and shares images, thoughts and stories about tribal life, maybe we could save part of our world’s precious cultural heritage from vanishing. I feel that we must try to let them co-exist in these modern times, by supporting their cause, respecting their habitats, recording their pride, and helping them to pass on their traditions to generations to come. Only that way can we help them keep their way of life for as long as possible.

Other than the beauty you document with your photos, what message do you hope readers come away with?

Mainly that there is a pure beauty in their goals and family ties, their belief in gods and nature, and their will to do the right thing in order to be taken care of when their time comes. They know what makes them happy, and they choose to live that life. –Bret Love; all photos by Jimmy Nelson courtesy of teNeues

IF YOU LIKE IT, PIN IT!

If you enjoyed our interview with Jimmy Nelson on Before They Pass Away, you might also like:

INTERVIEW: National Geographic Photographer Peter Essick

INTERVIEW: NatGeo’s Scott Wallace on the Expedition to Save Amazon Tribes

DOMINICA: Exploring Kalinago (a.k.a. Carin Indian) Territory

SOUTH AFRICA: A Zulu Homestay in Simunye Zulu Village

PERUVIAN AMAZON: A Shaman’s Blessing & a Ribereños Village

GEORGIA: The Cherokee County Indian Festival & Pow-Wow