Water Wonders

A Father-Daughter Story of Growth Through Adventure

My daughter was a water baby from the moment she was born. Though it’s been 11 years now, I can still vividly recall her at the age of six months, sitting in her baby seat in the bathtub, splashing water everywhere and giggling with unbridled glee. But what was once a simple pleasure has gradually become a burgeoning passion for father and daughter alike.

She started learning to swim at the age of three, right around the time her mother and I went our separate ways. With 50% custody, I was determined to be a hands-on dad, so I’d pick her up from summer camp and take her to the pool, where we’d play Sharks & Minnows and Marco Polo for hours.

A shy, sweet child by nature, in the water my daughter became fearless, jumping off the diving board with a joyful sense of abandon and making new friends easily. Going to the pool together became prime father-daughter bonding time.

Father-Daughter Story #1: Bahamas

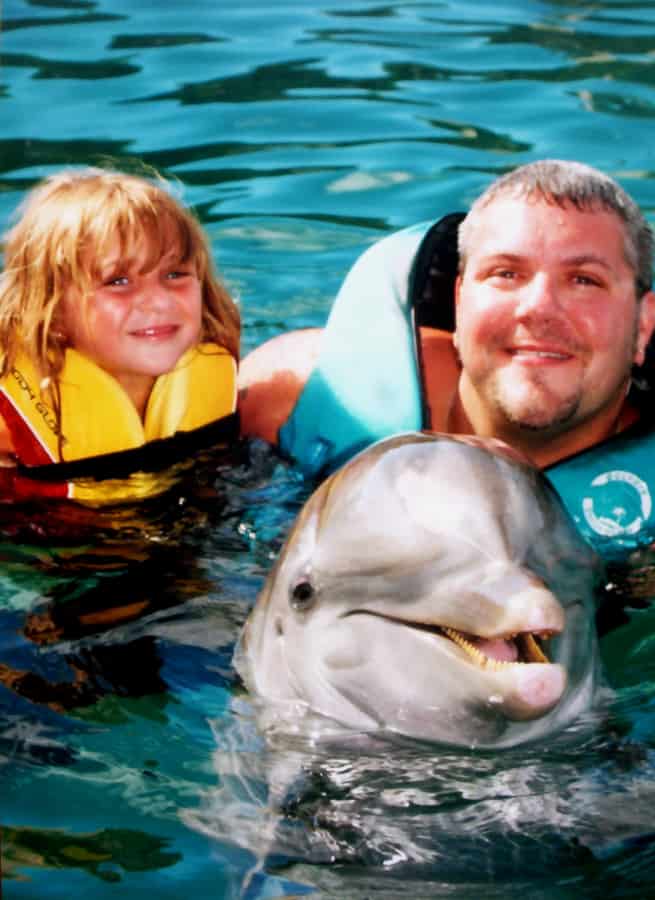

In 2007, just before she turned six, Alex and I embarked upon our first big adventure overseas. She had expressed nervousness about entering first grade, and was worried about the added pressures of homework, tests and grades. To honor the milestone I took her to the Bahamas, where she swam with dolphins on Blue Lagoon Island (note: This was years before I saw The Cove and stopped visiting dolphinariums).

There was palpable fear in her eyes as she treaded water in the ocean-fed holding pen where the dolphins came to swim and play with visitors. But as they flipped, splashed and propelled her through the water by pushing her feet with their noses, she eventually warmed up to their charms and gamely posed for pictures while hugging “Princess” close.

“I was a little scared at first because I’d never been in the water with animals that big,” Alex recalls. “But the dolphins were so friendly. I loved when they did the foot-push through the water. After we got to swim with them, I didn’t want to leave.”

Later we went snorkeling on a coral reef, in an area where 3-foot nurse sharks circled below. As we held onto a rope attached to the catamaran, the small sharks gradually circled closer to the surface, until Alex was so scared I had to take her out of the water. I was certain she’d want nothing else to do with them.

But when our guides got everyone onto the boat and started chumming the water to induce a feeding frenzy, she held tightly onto my hand and moved next to our guide to watch. Suddenly one shark chomped aggressively into a fish head he’d put on the end of a stick, and he quickly pulled it onto the edge of the boat so that we could watch it devour its prey from close range.

I swear my daughter’s eyes nearly popped out of her head at that moment, but afterwards she couldn’t stop raving about how cool it was. By the end of the trip, she was hooked, and the beach, ocean and marine life became borderline obsessions.

Father-Daughter Story #2: Sanibel Island

As time went on, Alex began studying environmental conservation at school, and her interest in nature and science grew. We took trips to Sanibel Island, learning about animals at the Center for the Rehabilitation of Wildlife, Ding Darling National Wildlife Refuge, and on dolphin-watching cruises.

It was on Sanibel in the summer of 2011 that I realized Alex’s interest in marine life had become more than mere childhood curiosity after spending time at the Sanibel Sea School. Founded in 2005 by J. Bruce Neill, a PhD in conservation biology, the school offers various programs that give visitors of all ages an in-depth overview of Sanibel’s abundant marine life and explain the importance of preserving it.

After a brief tour of their small facility, Bruce led us out into the shallow waters near Sanibel’s historic lighthouse. There, we met some of Sanibel’s intriguing marine life (including sand dollars, bivalves and a fighting conch) and learned why Sanibel Island is considered one of the world’s best shelling beaches. Basically, the barrier island lies near where the Gulf of Mexico meets the Atlantic, the confluence of which churns up everything on the ocean floor.

This was not the dry, boring education so many kids complain about. This was an interactive experience with the wonders of the ocean, and Alex was clearly intrigued.

“It was interesting to learn how the currents brought lots of shells to Sanibel,” she says. “It was also really cool when we caught little fish in a net and looked at them in a bucket. That was the first time I got to do an experiment with marine science. I realized that I wanted to do what [Sanibel Sea School] did, studying the ocean and teaching people about it.”

Father-Daughter Story #3: Bermuda

If Sanibel Sea School provided a spark of inspiration for Alex’s interest in marine science, our trip to Bermuda REALLY stoked the fires.

We went to visit the Bermuda Institute of Ocean Sciences, which was founded in 1903. Education Coordinator Alexander “Dready” Hunter explained some of the organization’s current projects, including studying the grasses of Bermuda’s Sargasso Sea and the effects of climate change of ocean acidification. We got a tour of their research laboratory, which was lined with of maps of the ocean, various graphs, and a massive fish tank holding several of the invasive lionfish species.

My daughter seemed bored while I interviewed Dready about educational programs, but she lit up when the BIOS team asked if she wanted to help with their experiments to see how raising H2O acidity impacts a coral reef’s growth. Various coral had been placed into 9 bins, and Alex helped them test the water, dipping test tubes into each bin as they took notes. The cylinder pumping the water with the highest acidity was covered in corrosion, and it wasn’t hard to imagine the long-term impact that could have on marine life.

Afterwards, we got a tour of the touch tanks. Dready showed Alex how new coral is grown on small squares that reminded us of Spongebob Squarepants, let her hold a purple sea star and asked her to feed a sea anemone. Even the littlest of creatures– a tiny crab hiding cautiously under the anemone like a child behind its mother’s skirt– was, to her eyes, a marvelous wonder to behold.

But my little animal-lover’s favorite part was Dready’s discovery of a sea hare, which had somehow gotten stuck under a rock. She shouted excitedly for me to come see, and cradled the creature gently in her hands as I snapped a few photos before she set it free. Alex was elated, and it became obvious that my daughter was more intrigued by the hands-on side of marine science than lab work.

The poignancy of the moment for Dready was obvious. “When you can get up close to the smaller stuff that makes up the vast majority of the marine ecosystem and get kids fascinated by every level of it, that’s of primary importance,” he insisted. “When a kid takes an interest in marine conservation, it justifies all the hard work we put in. That’s why I do this.”

Later, during a visit to the Bermuda Aquarium, Museum & Zoo, we learned about sea turtle conservation from Dr. Mark Outerbridge of the Bermuda Turtle Project. He explained that five of the world’s seven sea turtle species pass through Bermuda’s waters, and that the green sea turtle is a keystone species whose population health is crucial to the area’s sea grass (which offers protection for fish).

My daughter had dreamed of seeing sea turtles up close for years, tantalized by my tales of snorkeling with them in Hawaii and the Riviera Maya. She’s painted pictures of sea turtles, has a collection of sea turtle figurines she’s collected, and has even listed them among her favorite animals in school reports. So she practically exploded when Outerbridge asked if she’d be interested in feeding some sea turtles.

After grabbing heads of lettuce from a cooler, he led us to a huge swimming pool enclosure that held five of the largest sea turtles I’d ever seen. Alex looked blissful as she hand-fed them all, piece by piece. The turtles seemed to enjoy it as well, clamoring over each other like clumsy kittens.

“They were creating this big turtle pyramid,” Alex recalls, “climbing on top of each other trying to get the pieces of lettuce. It was magical!” And although she says many things are magical, as only a tween-age girl can, I believe this moment may have been the most magical of all. For both of us.

Father-Daughter Story #4: Home

Back home, during a visit to the Georgia Aquarium, it occurred to me that my shy little girl isn’t so little (or shy) anymore. As Animal Interactive specialist Amanda Foster taught us about their 4R program (Rescue, Rehabilitation, Research, Responsibility) and field research on Beluga whales, I noticed Alex listening with rapt interest and asking intelligent questions, such as, “How did you get to work at the Aquarium?”

The answer– Foster went to FSU, with a Psychology major and a Marine Biology minor, volunteering there in the summer– led to a revelation: Alex can start volunteering at the Aquarium in three years and, after a year of working with the public, she can move behind the scenes and work with a species of her choice.

Her mind clearly reeled with the possibilities of getting to work with whales, dolphins or otters… and my mind reeled with the realization that my daughter is on the verge of becoming a teenager. Together, our travel adventures have helped her find her own unique path in this world, and we’re already talking about future steps towards making her marine science dreams come true. Next week, we’re heading to Mexico so she can swim with whale sharks and sea turtles in the wild for the first time.

Once, I led my daughter hand-in-hand to the swimming pool. Soon I’ll be dropping her off to work at the world’s largest aquarium. Whichever path she ultimately chooses in this life, as a father I can only hope I’ll be there to watch my little water baby shine… –Bret Love

If you enjoyed our Father-Daughter Story of Growth Through Adventure, you might also like:

How Mary Conquered Her Fear of Water & Learned To Love Scuba

Snorkeling With Sea Turtles in the Riviera Maya

Bora Bora: The Ruahatu Lagoon Sanctuary

INTERVIEW: Jean-Michel Cousteau on the Future of Marine Conservation