Interview With Charles Darwin Foundation

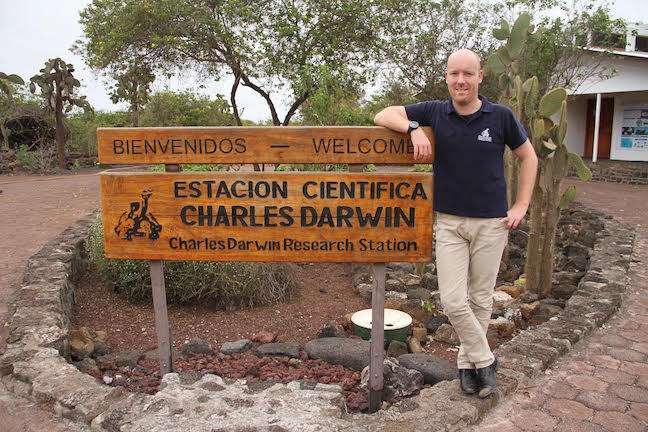

Executive Director Swen Lorenz

We’ve always felt a special connection with the Galapagos Islands. Not only because it’s an incredibly unique haven for nature/wildlife enthusiasts and an impressive model for responsible ecotourism management, but also because our trip there in 2011 really helped launched this site.

One of our favorite memories is our visit to the Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz island. It was there that we learned about the important scientific research the Charles Darwin Foundation has done since 1959 in an effort to conserve this unique ecological treasure, including bringing the Galapagos Tortoise back from the brink of extinction, eradicating invasive species and advising the government of Ecuador on how to manage Galapagos National Park sustainably.

So we were shocked to learn that the Foundation was teetering on the brink of bankruptcy a few months ago after the local mayor shut down their gift shop, which brings in an average of $32,000 a month. The problem came when the gift shop began selling items such as swimsuits, chocolates and artwork, and local vendors groused that the CDF’s shop was impacting their revenue. This was part of a larger issue in which locals complain that international tourism (which is largely based on small island-hopping cruises) doesn’t benefit them directly.

As we prepare for a return trip to the Galapagos Islands in June, we decided to reach out to Charles Darwin Foundation Executive Director Swen Lorenz to discuss the Foundation’s history, mission, problems and potential solutions, as well as why its scientific research is essential to conservation of the Galapagos Islands.

Let’s start off talking about the origins of the Charles Darwin Foundation. When was it formed, and what was its mission?

The Charles Darwin Foundation is the scientific advisor to the government of Ecuador on the conservation of the Galapagos Islands. Operating the Charles Darwin Research Station on Santa Cruz Island, we have more than 150 scientists working with us to create the knowledge necessary to protect this UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The CDF has held that role since 1959, with all our work privately funded through donations. No other private organization has a comparable role, and no other private organization has been in Galapagos for so long. The Foundation has had a crucial role in preserving the Galapagos, and its effects can be seen in all parts of the archipelago, inhabited as well as uninhabited.

The CDF was founded the same year the Galapagos National Park was established. Its founding was the result of a collaboration between the IUCN, UNESCO, the Ecuadorian Government, and a number of individuals. Unlike other biological field stations, we are not funded by a single university. We do work with a number of universities, but we have no “sugar daddy”: We work independently and raise our own funds. It’s a unique model, but has proven successful for over five decades.

Can you talk about the Foundation’s most important accomplishments?

Among the most successful projects is the breeding of Galapagos Tortoises. We started a research project in the 1960s because these animals (which gave Galapagos their name) were on the brink of extinction. Today, the population is up to around 50,000 animals, and not a single giant tortoise species is facing the risk of extinction. Visitors can now see them in large numbers in the wild, just as Charles Darwin did when he arrived in the Galapagos. That’s a huge achievement!

Over the decades, the Charles Darwin Foundation has also been involved in setting up a quarantine system to keep out invasive species. We researched the data necessary to create the Galapagos Marine Reserve, the world’s 4th largest marine reserve. We’ve trained more than 2,000 Ecuadorian students. We eradicated invasive species that harmed the local biodiversity: [Eliminating] the rampant goat population involved the largest eradication project ever undertaken in the world.

All of that was privately funded, without any financial support from the government. Since 1996, we have mobilized more than $50 million in funding.

When attracted you to the position of Executive Director of the Foundation?

It is quite simply the most exciting job that I can think of! Ever since I first came to the islands as a tourist in 2004, I’ve been hugely passionate about the stunning ecosystem and the amazing wildlife.

I pursued a number of other projects in Galapagos, including the founding of a school providing job training to local high school kids. Then I was offered the opportunity to run the oldest, largest private organisation on the island.

It’s a challenging job because the organization has to raise its funding every single year. However, running the Charles Darwin Foundation gives me the opportunity to make a real difference in the conservation of the Galapagos Islands. That’s what makes me get up in the morning!

Can you explain what makes the Galapagos such a unique ecological treasure?

The Galapagos was actually the first place on the planet to be designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site: They have registration #001 in the UNESCO register in Paris. That in itself says a lot! This is a treasure that needs to be preserved for all of mankind.

Anyone who has ever visited will understand why this place should be kept intact for future generations. You can wander around animals that have no fear of man, and will simply ignore you. Experiencing pristine, untamed nature in the Galapagos Islands is an experience that most visitors describe as life-changing. There is simply nothing comparable anywhere in the world.

The Galapagos Islands are also a microcosm of the social, political, economic and ecological changes occurring throughout the world. They not only teach us about where things have come from, but can also show us a path into the future. Striking a balance between the needs of humans and the natural world is particularly important in the Galapagos because of their unique, fragile ecosystems. But the relatively small, contained nature of the archipelago means that solutions are within our grasp, and these solutions can serve as conservation models for the rest of the world!

The Galapagos was added to the list of World Heritage Sites in danger in 2007. What are the major challenges currently facing conservation in the region?

On the conservation front, it’s the threat posed by the Philornis downsi fly, which came here in the 1960s, probably on a cargo boat. The larvae of this fly are killing off the nestlings of the local landbird population. The Galapagos have never ever lost an endemic landbird species. Now we are at risk of losing several, including some of the famous Darwin Finches. We are working extremely hard to prevent this from happening.

How do you eradicate a fly on an archipelago the size of Galapagos, where most of the land is totally inaccessible? This is where you need cutting-edge science to come in. The CDF did a similar project successfully a decade ago, when we brought under control an invasive insect that was decimating the mangrove forests. These are not necessarily the sexiest projects. But imagine the headlines if the Galapagos Islands lost several varieties of Darwin finches. It’s unimaginable!

We have issues with invasive species both on land and in the sea. In the Galapagos Marine Reserve we’re currently doing some exciting baseline work to establish how to best deal with invasive species under water. There is a lot more research to be done in this area. We strive to create data and scientific knowledge for many areas that Galapagos is so famous for.

This also includes sharks. Galapagos has one of the world’s last remaining abundant shark populations, but even today little is known about sharks. Where do they migrate? What are their breeding patterns? With our shark-tagging program we’re establishing information that will benefit the shark populations in the Galapagos Islands, but will also be of wider relevance for protecting these animals throughout the world’s oceans.

Some critics suggest that tourism to pristine ecosystems such as the Galapagos is harmful to the environment and the wildlife that inhabits it. How would you respond?

The Galapagos Islands get a fair amount of press, and one common theme that gets picked up on fairly often is that tourism is hurting the islands, or that the islands are being overrun by tourists. But this needs to be put into context.

The great naturalist and TV presenter Sir David Attenborough said that, without tourism, the Galapagos wouldn’t even exist anymore. Tourism provides a powerful financial incentive to preserve these islands.

But of course there are problems coming with tourism, and there remain many questions that need to be looked into, such as the carrying capacity of individual sites that have seen huge growth in visitor numbers and the ability of the authorities to effectively run quarantine systems. Increasing visitor numbers do bring additional challenges.

I’d like to see the tourism industry create stronger engagement of Galapagos visitors to get their support for funding conservation solutions. The numbers required in terms of funding are not very high. If more visitors make contributions to CDF or other entities, we can find sustainable solutions to the islands’ problems. Tourism can be a problem, but it can also be part of the solution.

I took a small-ship cruise to the Galapagos, but I’ve heard land-based tourism is on the rise. Is there a difference in the impact of land-based vs water-based tourism?

Statistics show that in recent years there has been strong growth in this kind of locally-based tourism in Galapagos. To some degree this is also an effect of the worldwide trend of tourists making their own travel itineraries based on interests and budget, and with technology providing easy access to information and enabling booking of trip components individually, even at the last minute.

There are positives and negatives. The upside is that there is a more equitable economic distribution of tourism revenue in the local community. Local companies are able to work without intermediaries, and tourists get to observe the human dimension of Galapagos.

The downside has been that there’s growing pressure on our scarce natural resources, and greater pollution. A lack of planning has led to reactions to the immediate needs of the market, with informal businesses being set up, and there has been a general trend towards offerings with lower price and lower quality.

Here, too, the government of Ecuador is working on defining a new ecotourism model for the Galapagos. The Ecotourism Project– led by the CDF in collaboration with the Galapagos National Park Service and the Ministry of Tourism, and funded by WWF– was created to find solutions for this problem. They make recommendations for the implementation of local policies that will help to develop a real community-based ecotourism, which can be linked to the traditional cruise-based tourism in order to ensure a right balance between nature-based travel and local-based experience.

What restrictions are in place to ensure that ecotourism in the Galapagos is responsibly managed, and who oversees/polices that?

There are regulations in place, some of which are among the best in the world, such as the system developed by the Galapagos National Park to limit the sites that cruise ships can go to. No system is perfect, but a lot has already been done towards this end.

Travelers can– and should– choose carefully among providers that have certification for sustainable management. I salute everyone who books through one of our travel partners, such as the International Galapagos Tour Operators Association, as this leads to funding coming our way, which we then invest into science for conservation.

There is a real shared responsibility among all players to work together to further improve the existing systems. There is only one Galapagos, and we need to pull together on one rope. Our organization’s view is, “Do visit, but please visit responsibly.”

Can you talk about the role the Charles Darwin Foundation and its Research Station play in educating visitors about the Galapagos and responsible wildlife management?

The CDF operates the Charles Darwin Research Station in Puerto Ayora, one of the top visitor sites on the island of Santa Cruz. We’ve been doing a lot to improve the quality of visitor experience there, including creating a trail for visitors to walk around the entire research station, adding plenty of interpretation material to look at, and installing a statue of Darwin as a young man. All of these improvements are currently in their final phase of being implemented.

We also have the most frequently visited social media channels of the Galapagos by far, which we use to inform and educate the public, both in English and Spanish. You can follow us on Facebook and Twitter.

Further investments along those lines are planned, and we are currently discussing this with the government of Ecuador. The CDF has very ambitious plans in the pipeline. And I would like to have the entire world be aware of what is being achieved here, not just those lucky individuals who actually get to visit the Galapagos.

The CDF has had some struggles lately: Your gift shop was closed down, locals complained that Galapagos tourism doesn’t benefit them and the Research Station had financial issues. Can you talk about these problems and the solutions you envision?

Last year, our organization faced a perfect storm. In July, local authorities shut down our souvenir store, which had been providing CDF revenue for almost two decades and had recently been enlarged. They cited “unfair competition” with local shop owners as the reason. This has cost us about $200,000 in lost income. The closure put a halt to our special fundraising campaign via our new donor wall, through which we had budgeted several hundred thousand dollars in revenue.

Around the same time we lost a long-agreed sale of our land in San Cristobal, literally days before the contract was due to be signed. All together, we lost nearly $1 million in income in 2014. When you are running an organization with a $3.5 million budget and virtually no reserves, that’s a huge blow. When our souvenir shop was closed, we started to experience a financial chain reaction. By December, the CDF was nearly three months behind with salary payments. Such a situation eventually takes you to a breaking point.

The CDF launched a public campaign to ensure it can keep going. In early 2015, we received $1.15 million in funding from The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust and the Lindblad-National Geographic Fund, who are both long-term supporters. Additionally, through our #SaveDarwin campaign, the CDF raised $400,000 from more than 400 generous and committed individual donors from around the world. These funds will be used to build a sustainable funding model, while developing a stronger, more strategic relationship with Ecuador’s government.

The Research Station is a major tourist attraction, with more than 100,000 visitors per year. Without it, fewer foreigners would visit Puerto Ayora, and the economic loss to the local community would be enormous. So we’re working on a political compromise to re-open the shop. But this episode significantly damaged the confidence of international donors, possibly permanently. The long-term effects of this have yet to be seen.

What goals do you have for the future of the CDF?

To achieve financial sustainbility for the Charles Darwin Foundation. For more than 50 years, the organization has lived hand-in-mouth. At times its survival was in question.

I’ve been building up the CDF’s ability to earn more income. If we continue on this path for a few more years, the CDF will have become financially sustainable for the first time in its history. This will significantly change and improve the way how we can provide science for the conservation of the Galapagos Islands. –Bret Love; photos of Swen Lorenz provided by the CDF, all other photos by Bret Love & Mary Gabbett

If you enjoyed our interview with Swen Lorenz of Charles Darwin Foundation, you might also like:

INTERVIEW: Matt Kareus of IGTOA on Galapagos Conservation

Darwin’s Paradise: Galapagos Islands Animals, Ecotourism & Adventure

PHOTO GALLERY: The Birds of the Galapagos Islands

GALAPAGOS ISLANDS: San Cristobal & Genovesa

GALAPAGOS ISLANDS: Genovesa & Fernandina

GALAPAGOS ISLANDS: Isabela & Santiago

GALAPAGOS ISLANDS: North Seymour & Bartolome

GALAPAGOS ISLANDS: Santa Cruz & Espanola