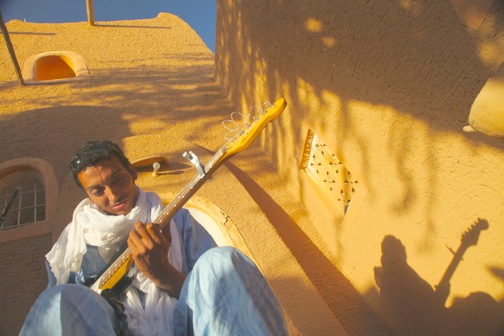

Taureg Guitarist Bombino

On His Nomadic Culture, Guitar Gods & the Future of Africa

It’s been a while since a new artist has emerged onto the world music since accompanied by the sort of buzz surrounding Omara “Bombino” Moctar. The Tuareg guitarist’s backstory is rich, with his family being forced to flee their home in Agadez, Niger and seek shelter in Algeria when he was just a boy. After learning to play guitar as a teen, Bombino and his family ultimately returned to Niger, only to find guitars banned when yet another Tuareg rebellion erupted in 2007. Two of Bombino’s fellow musicians were executed, forcing Bombino to live in exile in Burkina Faso.

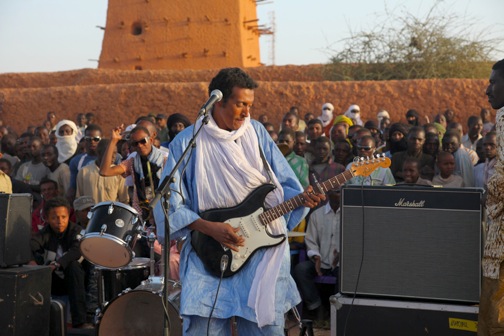

He was finally able to go back to Niger last year, where he performed a triumphant concert at the base of the Grand Mosque in Agadez. Now, he’s releasing a critically acclaimed album (which has earned him comparisons to Ali Farka Toure and Jimi Hendrix) named after his hometown, and is the star of a new documentary film, Agadez, The Music & The Rebellion. We recently spoke with the 31-year-old phenom about his nomadic culture, the turbulence of his childhood, and his hopes for Africa’s future.

Your bio says you spent your childhood learning the survival skills necessary to a nomadic lifestyle. For our readers who don’t know much about the Tuareg, what was that lifestyle like?

The Tuareg are a nomadic people who herd camels, goats and sheep. The rhythm of their life depends on the seasons because they are always on the way to getting pasture and water for their animals. The men organize caravans through the desert to get salt and dates from the North (North Africa) and exchange them for millet and cereals in the South (West Africa). The women educate children by teaching them the Tuareg moral code, named Aschak– which is formed by moral virtues such as courage, generosity, feeling good about the culture, responsibility, endurance – and our language and alphabet, called Tifinagh. Due to the availability of water during the rainy season, it remains the best time for the nomadic peoples because they are saved from seeking water from the wells. In the bush, tents are our houses, and we enjoy the beauty of the life in the desert, where we have space and tranquility. We breed animals in the bush and spend all day guarding them. When we come back to the encampment at the end of evening, sometimes we stay there without food and water in order to resist the lack of water in the desert. Then we milk the animals, get dinner and go to the place of night meeting, where people make fire, prepare tea and discuss history, recite poetry and sing. This is the nomad lifestyle.

What are your memories of music during your childhood in Niger?

My memories are the first songs of Intayaden with this song named “Itam Chilan,” meaning “Seven Days.” It is a revolutionary song that any Tuareg knows and it is influenced by Ali Farka Toure and Tuareg traditional songs.

You discovered the guitar when your family moved to Algeria in 1990 to escape the violence of the Tuareg Rebellion. How do you think making this discovery at this tumultuous time in your life influenced the artist you are today?

It was a difficult moment in my life. We left Agadez to Algeria when I was very small. The guitar was a new instrument integrated in the life of the Tuareg, who used it for revolutionary messages. When I saw this instrument for the first time I fell in love with it. But it is very difficult to get a guitar, as they were not easily available. Even now, there is no musical instrument shop in Agadez. People who have a guitar are guarded about it, so it was difficult to find an instrument to play. I saw my parents fighting for their rights, persecuted by the Niger government and forced into exile in Algeria and Libya. I saw the importance of the guitar in our life, as it mobilized young people to go to the field of fighting. I think these elements seriously influenced me to become the artist I am today.

Guitars were banned by the authorities when you returned to Niger in 2007. Why were they threatened by music, and how did you manage to hone your talent in such a hostile environment?

The guitar is an instrument of expression, used to sensitize the Tuareg about their rights and their fight, as well as to sing about the beauty of the nomad life. This is why the authorities forbade the guitar during the first rebellion in Niger and Mali from 1990 to 1995 and again in 2007 to 2010. When the government and rebels agreed about peace, the guitar was allowed again and musicians could play without any problem for marriages, baptisms and official ceremonies. I honed my talent during these times, playing with my friends. We would organize parties and go to the bush to play guitar.

Who were the guitarists whose work most influenced you to become serious about the craft?

They are Bebe Haja, my first teacher; Abdallah Oumbadougou, who is a great guitar player in Niger; Ibrahim Abrayboun of Tinariwen; Ali Farka Toure and Jimi Hendrix. I found some clips of Jimi Hendrix that I watched many times. I really liked his manner of playing guitar.

What can you tell me about the documentary Ron Wyman made of you, Agadez, The Music & The Rebellion?

It talks about our music, the Tuareg peoples, the nomadic life, its problems and our perspectives in our fight for our rights. It shows Agadez and explaining its history to the world. I love it very much. Thanks to Ron for this wonderful job.

Your debut album is named after the region in which you grew up. Why was it important for you to pay tribute to Agadez?

It is my native region, where all of my ancestors lived. It is an honor for me to introduce the world to my region, our culture, and our problems through music. It was very important for me to pay tribute to Agadez.

Africa has seen quite a lot of sociopolitical turmoil this year. What is your hope for the future of Africa, and for Niger in particular?

My hope for Africa is peace, tranquility, and social and economic development for the poor population. I refuse war as a system to claim rights. I prefer dialogue between all the communities in the world, and in Niger in particular. We are human: We have strong minds, and we can use them to resolve our problems. –Bret Love

If you enjoyed reading our Bombino interview, you might also like:

A Musical Passport: 40 World Music Artists From Green Global Travel’s First Year

Sierra Leone Refugee All-Stars Interview