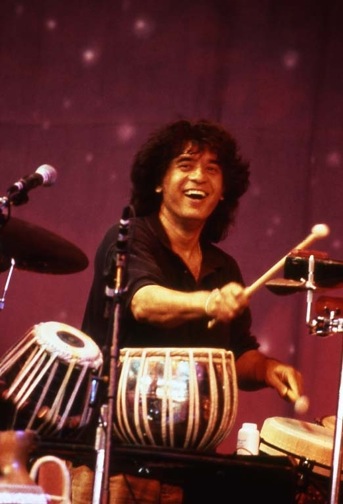

Zakir Hussain

India’s Legendary Percussionist

In the annals of North Indian Classical music, few artists boast more international acclaim (or name recognition) than master percussionist Zakir Hussain.

Son of tabla virtuoso Alla Rakha, Hussain was raised surrounded by legends like Ravi Shankar. By the age of 19 he was accompanying Shankar and other Indian music icons, and in his early twenties he was working with high-profile Western musicians such as George Harrison and jazz guitarist John McLaughlin. He is perhaps best known in America for his collaborations with Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart in numerous projects, including Diga Rhythm Band, Planet Drum and Mystery Box.

Now Hussain has embarked on a cross-cultural collaboration with banjo player Bela Fleck and bassist Edgar Meyer, fusing elements of jazz, bluegrass and Indian music to create a stylistic fusion unlike anything you’ve ever heard. We recently spoke to the tabla master as the trio embarked upon its first tour in support of their excellent album, The Melody of Rhythm.

I’ve always been intrigued by the complexity of Indian music and the dedication it takes to master it. At what age did you begin playing percussion?

The first thing is to understand that, for any music, it is important to be in that environment, soaking in all the information, just living it. That’s what my life was all about. As a young child, the rhythms and sounds were constantly there, with students practicing, my father teaching, playing recordings and going to concerts. By the time I was 3 or 4 I was recognizing tones and patterns. I was involved in it all day, but more from looking in rather than being in. I saw my father interacting with all these students and musicians and the adulation coming to him. He became larger than life, almost godlike, and I wanted to connect to him in that way. By the time I was seven I was playing in school concerts.

How did your dad respond to your budding interest in tabla?

He played reverse psychology! (Laughs) Instead of pushing me into doing it, he just kept away. The more he kept away, the more I wanted to be in it. So when I was seven, he said, “So you want to study this?” He would wake me up at 2 a.m., and I wanted to open up my tabla, but he said, “No, we’re going to talk.” For the next 4 or 5 years, we did that every night. I would sit in front of him and he’d talk with me about rhythms, sing the patterns and have me sing them back, and talk about old masters and great musicians of that time. I cannot explain the ecstasy of those moments. By age 12, I was being sent out to play concerts by him and with him, as his apprentice. At the age of 19, I was sent as his replacement to perform with Ravi Shankar in New York, and my life changed forever.

Indian Classical music has historically been dominated by purists. What was the reaction when you first started collaborating with Western musicians in the 1970s?

By the time I started, Ravi Shankar and my father had already done it, so it wasn’t that much of a shock. I’m a rhythm player, and rhythm is universal. When my father made a record with Buddy Rich, it seemed very natural. What was interesting for me was that my father was very supportive of whatever I was doing. The only thing he said to me was, “Make sure that you have your own identity and do the thing that you do best, which is playing tabla.” As long as I kept playing my Indian concerts, it didn’t matter what else I did. It was very clear to connoisseurs that I’m equally at home in both mediums. But, having said that, this purist thing is something that happens in all forms of music. I remember when I was playing with John McLaughlin, there were jazz purists that were like, “What the hell is going on?” In a way, I think it’s good because you need purists to preserve what has been.

What is the excitement for you in combining cultural influences with other people?

The excitement is learning. My father once told me, “Don’t try to be a master: Just be a good student.” Every time I play with a musician I’ve never played with before, I learn something new. When play with Bela Fleck, John McLaughlin or Mickey Hart, I learn from them. That allows me to expand my table repertoire into territories it’s never gone before. The tabla is a unique instrument in the sense that it has the capacity to absorb whatever information to print on it. It will bend to the needs of the moment.

Your latest collaboration finds you working with Bela Fleck and Edgar Meyer. How did that trio come together?

I still wonder about that– bass, banjo and tabla?!– but they have something in common in that they can be melodically supportive or rhythmically supportive to the main instrument. It was Edgar and Bela who sought me out. The Nashville Symphony was opening a new concert hall, and for the opening they asked Edgar and Bela to write a concerto. They said they’d only do it if Nashville would allow them to bring a third musician in, and they wanted me. So I got involved in it because of them.

Was there great chemistry right away?

When I first met them, I thought, “I’m going to ask them to teach me about bluegrass or 4-part harmony.” But before I could say anything, they said, “Can you please teach us some Indian rhythmic exercises and scales?” I was like, “What? I want to learn from you!” It’s so amazing to find like-minded people, and that led to us getting to know each other on many more levels. Now it’s become a family. I just had a premiere of my concerto in Washington DC, and in the third row were Bela and his wife and Edgar and his son. It was like, “Ok, one of the family members is having a big moment and we all must be there to support him.” Interacting with Bela and Edgar on some many different levels makes our music so much more complete. It’s an amazing thing to be able to bring all life’s moments into our little time together on stage.

The liner notes of The Melody of Rhythm suggest that the trio has more projects in mind for the future. Where would you like to see the group go from here?

Over the years, when you play together, you discover things about each other. The more you interact with people, the more you touch on little details– the coil unwinds and the knots open. Edgar, Bela and I are just starting to go through that and finding that there are so many ways our instruments can speak to each other on so many levels. That interaction brings to the front other ideas of composition. The idea on this tour is to be able to record what we play live. We have these ideas and we bring them to the stage, then we work with the audience on how the piece will unwind, emerge and find its personality. I guess the idea is to let the music to find its spirit and character through the tour. Hopefully, by the time we’re done, we will have a new album! –Bret Love

If you enjoyed reading our Zakir Hussain interview, you might also like:

A Musical Passport: 40 World Music Artists From Green Global Travel’s First Year

Sierra Leone Refugee All-Stars Interview