My heart aches. I feel as if I cannot breathe. I’m halfway through a tour of the Kigali Genocide Memorial Center, which opened in 2004 on the site where 250,000 victims of the Rwanda genocide were buried in mass graves. I find myself so overwhelmed that I have to go outside to get some air.

Strolling among those graves in lovingly landscaped gardens filled with palms, roses, trellised vines and bamboo trees, I slowly regain my composure. But the devastating emotional impact of visiting the memorial and its graphic depiction of Rwanda history still lingers now, more than a year later.

It’s not as if I didn’t know about the Rwanda Genocide, in which more than a million Tutsi and moderate Hutu were butchered by Hutu extremists (known as the akazu) over a 100-day period back in 1994.

My best friend, who was working with the Peace Corps in neighboring Burundi, was evacuated by UN tanks as the brutal, ongoing civil war spread across borders. But knowing that something happened and understanding how and why it happened are two very different things.

The history of the Rwanda genocide that you’ll learn at the Kigali Genocide Memorial will leave you deeply shaken, stirred and saddened.

But in order to truly appreciate the ways in which community-focused ecotourism is helping Rwanda to heal and rebuild itself, you must first understand how those tragic events of 1994 came to pass.

“We Did Not Choose To Be Colonized”

The Berlin Conference of 1884 assigned Rwanda’s territory to Germany as part of German East Africa.

Back then the nation was comprised of 18 different clans, all part of the Banyarwanda ethnic/linguistic group. The Hutu and Tutsi were socio-economic class distinctions that could be changed: If you owned 10 or more cows, you were Tutsi. Any less and you were Hutu.

When Belgium took control of Rwanda during World War I, it began nearly 40 years of hands-on colonial rule.

The Belgians brought Christianity, a centralized power structure, and infrastructure development that improved agriculture, education, health and public works.

They also brought heightened racial tension via identity cards introduced in 1932. Like the Jews in Germany, Hutu were forced to identify themselves as such. Even wealthy Hutu could no longer become Tutsi.

Rwanda’s Tutsi King Yuhi Musinga (a.k.a. Yuhi V), who had been in power since 1896, resisted Belgian colonial rule and refused to be baptized as a Roman Catholic.

So in 1931 he was deposed and exiled by the Belgians and succeeded by his eldest son, Charles Rudahigwa Mutara III, who consecrated Rwanda as a Christian nation in 1946.

During his reign, the Catholic Church’s Hamitic ideology promoted the notion that Tutsi were inherently superior.

Belgians required that Tutsi and Hutu children be educated in different schools. They forced impoverished Hutu laborers to build roads and raise crops for export.

By 1959, the people of Rwanda (which also included forest-dwelling pygmies known as the Twa) were divided by race, with the 84% majority Hutu oppressed by the 15% ruling Tutsi minority.

“Killed Just Because of Their Ethnicity”

The situation in Rwanda started to unravel shortly after King Rudahigwa’s death in 1959. The country was still ruled by Belgium as a UN Trust Territory, with guidelines requiring that it be prepared for independence.

But the Rwandan Revolution changed everything.

Tutsi leadership, growing tired of colonial occupation, pushed for independence to cement their power.

The Belgian government and the Roman Catholic Church threw their support behind an increasingly vocal Hutu elite, which called for majority rule.

False rumors arose that Tutsi activists had murdered a Hutu chief, and riots and arson attacks on Tutsi homes spread across the country.

The Belgians brought in Colonel Guy Logiest to establish order and protect the Hutu, replacing the Tutsi as chiefs and sub-chiefs and allowing anti-Tutsi massacres to continue.

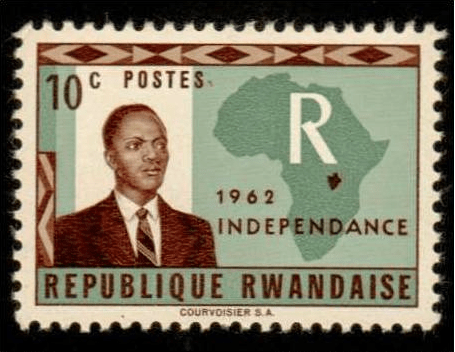

Hutu leader Grégoire Kayibanda, founder of the militarized Hutu Emancipation Movement Party, became Rwanda’s first elected President and declared the nation an autonomous republic in 1961.

More than 335,000 Tutsi fled the violence in Rwanda and became refugees in neighboring Burundi, Congo and Uganda.

Some exiles wanted to negotiate their return with the Hutu peacefully, while others formed armed militia (known by the Hutu as the inyenzi, or cockroaches) and launched attacks in Rwanda that led the government to kill thousands of Tutsi in retaliation.

Rwanda may have gained its independence from colonial forces, but the power vacuum would ensure no peace or prosperity for decades to come.

“It Was Like a Bad Dream”

After Army Chief of Staff Juvénal Habyarimana seized power via a coup d’état in 1973, the situation in Rwanda seemed to settle down for a while.

But as the relatively moderate Habyarimana’s policies became more dictatorial, discord arose, both within the Hutu ranks and abroad.

Led by Fred Rwigyema and Paul Kagame, the Rwandan Patriotic Front was formed in 1987 by Rwandan refugees trained by and serving in Uganda’s military.

In October 1990 they launched the Rwandan Civil War, sending 2,500 soldiers to invade their homeland and advancing 37 miles before being rebuffed by a mixture of Rwandan, French and Zairian military forces. This began 2.5 years of hit-and-run guerrilla attacks, designed to maximize fear and the element of surprise.

Mediation brought a temporary cease-fire in 1992, but massacres of Tutsis by radical Hutu extremists known as the Interahamwe continued. So the RPF launched a major offensive in 1993, while President Habyarimana negotiated a $12 million arms deal that included paramilitary and financial support from the French government.

The Arusha Accords, signed in August 1993, created a peace agreement for the sharing of power between RPF rebels and the Rwandan government.

But it also stripped the President of certain powers, creating a rift among the Hutu. The rising “Hutu Power” movement viewed the RPF as a threat on reinstating the Tutsi monarchy and enslaving Hutus. It was an uneasy peace at best.

“Prepare for the Apocalypse”

On April 6, 1994, a plane carrying Juvénal Habyarimana and Burundi president Cyprien Ntaryamira was shot out of the sky during its approach into Kigali.

An informant told UN officials that the Interahamwe, led by Colonel Theoneste Bagosora, planned to kill 1000 people every 20 minutes. They did nothing. It was the beginning of one of the worst massacres in modern world history.

Within a few hours of the President’s assassination, extremists had blocked roads throughout Rwanda and started going door-to-door in search of Tutsis and their Hutu sympathizers.

Neighbors turned on neighbors, slaughtering them using machetes and clubs. Women and children were specifically targeted in order to ensure there were no future generations of Tutsi to exact revenge.

Over the next 100 days, an estimated 1,174,000 Rwandans were murdered (a rate five times faster than the height of the Holocaust in Nazi Germany).

There were over 300,000 orphans. Around 40% of the nation’s population was either killed or displaced, fleeing into Uganda, Tanzania and Zaire (now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo).

The sole bright spot for the Tutsis was the Rwandan Patriotic Front.

Paul Kagame (who led the RPF after Fred Rwigyema’s death in 1990) launched a 3-pronged attack from the north just after the genocide began. By mid-June he had expanded his army by recruiting/training Tutsi survivors and began attacking government forces in Kigali.

The RPF finally took Kigali on July 4, and conquered the northwestern border town of Gisenyi two weeks later. The interim government headquartered there was forced to flee into Zaire, and the Rwanda genocide was officially over.

You can read this history and much more at the Kigali Genocide Memorial Centre.

You can watch videos that show the country’s tragedy and trauma. You can walk through rooms filled with thousands of photos of lost loved ones and see the bloody clothes they were found in, skulls cracked and pierced by blunt force trauma. It is gut-wrenching stuff, to say the least.

The Aftermath of the Rwanda Genocide

After the genocide ended, Kagame’s forces became Rwanda’s national army, with Kagame serving as Vice President of Rwanda and its Minister of Defense.

Pasteur Bizimungua– a Hutu who had served as a civil servant under Habyarimana before joining the RPF– was appointed President and oversaw the rebuilding of Rwanda’s infrastructure.

Kagame worked to portray the new government as inclusive rather than Tutsi-dominated, and removed ethnicity from citizens’ ID cards.

Determined to prosecute all perpetrators of the Rwanda genocide, the government arrested over 120,000 suspects.

With overcrowded prisons and a sluggish criminal justice system (many lawyers and judges had been murdered or fled the country), the country introduced Gacaca– a system based on traditional Rwandan justice– in 2001.

The village-based Gacaca courts were designed to establish truth about acts of genocide, accelerate the legal proceedings for those accused of Genocide Crimes, eradicate the culture of impunity that led to the genocide, and help Rwandans to find closure, acceptance and forgiveness.

The process brought criticism against the Rwandan government, including accusations of civil rights violations and corruption.

But it also helped families find murdered relatives’ bodies, brought tens of thousands of criminals to justice, and helped begin the reconciliation process between the Hutu and Tutsi people.

Around 12,000 local courts tried over 1.2 million cases at a cost of $4 million, compared to the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, which indicted 93 people at a cost of $1 billion.

Paul Kagame was widely criticized for partnering with Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni to launch two Congo Wars against Hutu militants in the DRC.

There were accusations of human rights violations by the Rwandan Army, as well as suggestions that the wars were as much about revenge and exploiting the Congo’s mineral wealth as they were about defending Rwanda. (For more info on these criticisms, check out the balanced 2013 reporting in The Guardian.)

But Kagame’s ascension to the Rwandan presidency in 2000 ushered in a hopeful new era the likes of which Rwanda hadn’t seen in a century. And his inspired vision for the future would ultimately turn the country into one of Africa’s fastest-growing economies.

Vision 2020

Launched by Kagame in 2000, Vision 2020 was an ambitious development program designed to transform Rwanda into a knowledge-based middle-income country, reducing poverty and health problems and making the nation more united and democratic.

The President consulted with experts from China and Singapore before tackling a broad array of goals, including reconstruction of the country, good governance, developing the private sector, and improvements in transportation, health, education and agricultural production.

Rwanda’s resulting economic development proved staggering, with an annual growth of around 8% per year and a per capita GDP that nearly tripled from 2000 ($567) to 2013 ($1,592).

Under Kagame’s leadership, peace, security and foreign investment in Rwanda are at an all-time high, while corruption is relatively low (ranked 8th out of 47 countries in sub-Saharan Africa).

Its roads and buildings have been rebuilt, a 1,400-mile fibre optic telecommunications network has been installed, education investment has raised the literacy rate to over 75%, and mortality rates from communicable diseases have sharply declined.

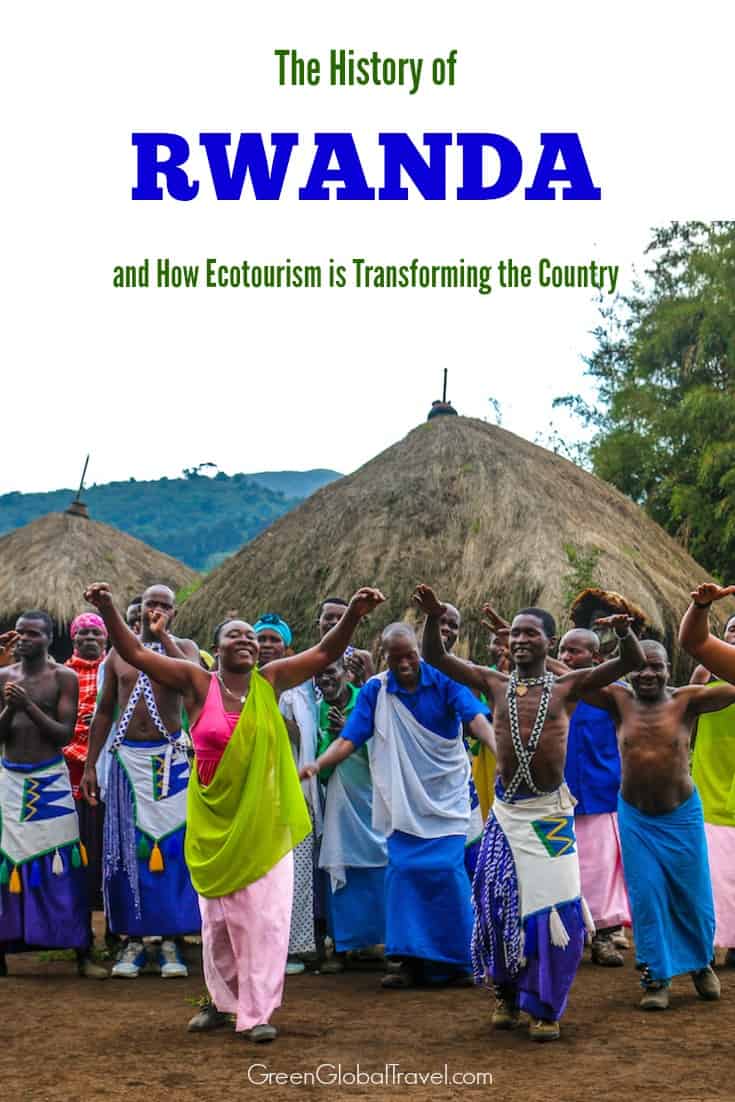

Ecotourism in Rwanda

So what does this mean for travelers? Tourism is one of Rwanda’s fastest-growing sectors thanks to its growing perception as a safe destination.

Thousands of tourists flock to Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park each year to make the trek to see its famed Mountain Gorillas in the wild. But the country boasts a number of other incredible ecotourism attractions that are worth discovering.

There are Chimpanzees, Blue Monkeys, Colobus Monkeys and L’Hoest’s Monkeys in Nyungwe Forest National Park, an area where vibrant green rainforests are offset by equally verdant tea plantations.

There’s a traditional African safari experience at Akagera National Park, where Elephants, Giraffes, Zebras, Leopards and Lions roam and very few tourists visit.

There’s the family-friendly vacation vibe of Lake Kivu. And there are the endless mountains that earned Rwanda its nickname, The Land of a Thousand Hills.

It’s been said that the future of any society depends on its ability to reconcile with its past. Back at the Kigali Genocide Memorial, I watched as a group of local schoolchildren walked through an area where over 250,000 victims of the Rwanda genocide were to laid to rest. They were laughing and smiling, too young to remember the brutal realities their parents faced 20 years ago.

As the leaves whispered softly in the morning breeze, it was easy to imagine the voices of the dead urging them to remember, and to learn from the tragic mistakes of Rwanda’s past. –Bret Love

If you enjoyed reading about Healing Wounds of the Rwanda Genocide, you might also like:

Our Interview on Rwanda for the Where Else To Go? Podcast

INTERVIEW: Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund CEO Tara Stoinski

Baby Gorilla in Volcanoes National Park

Trekking Rwanda’s Parc National des Volcans