The Bee Gees, Rites of Passage & Staying Alive

It was weird to learn last night that Robin Gibb had died after a long and difficult battle with cancer. Weird not only because, as a child of the ’70s, the Bee Gees provided the hip-shaking soundtrack to to my pre-adolescence, but also because Mary and I had just been talking about the weight of their influence on me earlier in the day.

The conversation was inspired by a major rite of passage my daughter will be going through on Thursday: Graduating elementary school. The past few weeks have been filled with preparations for this major life event, from a field trip to her new middle school and an orientation session for parents to planning details of our forthcoming celebratory dinner. I must admit, this transition in my child’s life has me a little emotional about the reality that my daughter is gradually growing up, which led to reflections upon my own graduation.

I grew up in Atlanta, in a suburban neighborhood afflicted by post-integration “white flight.” When I started at Snapfinger Elementary School (where, coincidentally, comedian Chris Tucker went a few years later), the racial mix was around 50/50. But by the time I graduated in 1979 I was in the vast minority (my high school was 98% black, 1.5% Asian, and .5% miscellaneous). As a result, the sounds of disco and funk were HUGE at my school, and I listened to artists like Chic, KC & the Sunshine Band and Donna Summer religiously.

When the Bee Gees’ Saturday Night Fever soundtrack came out in 1977, it immediately became my favorite album ever (years later, during my career as a celebrity interviewer, I had John Travolta sign my double vinyl album). Classic songs such as “You Should Be Dancing,” “More Than A Woman” and, of course, “Stayin’ Alive” were in constant rotation on my record player, and my best friend Dennis and I must have snuck in to see the movie’s R-rated version a half-dozen times over the course of a summer.

In retrospect, Travolta’s Tony Manero comes across as an immature lout. But to two suburban white kids whose only late-teen role models were substance-abusing rednecks who cranked Lynryd Skynyrd and drank cheap beer as often as they used racial slurs, Manero seemed like the KING: He was good-looking, a great dancer, and all the ladies loved him. Manero’s Italian ancestry made him seem exotic; the fact that he was from Brooklyn made him seem dangerous; and the fact that he could move like that gave him sheer animal magnetism. It wasn’t long before I was urging my more rhythmically gifted black friends to teach me some moves.

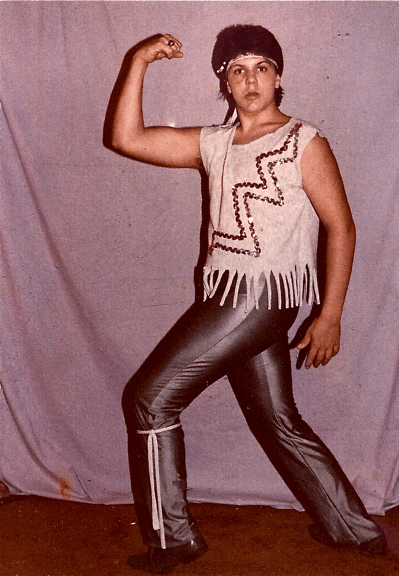

Back then, elementary school went through 7th grade. Due to skipping a grade, I was only 11 years old when I graduated (the same age my daughter will be in August). I can remember effortlessly my excitement when my parents took me to buy a suit– my first ever– for graduation, and I chose a tan corduroy leisure suit that couldn’t possibly have looked more like the ’70s. Of course, summertime in Atlanta isn’t exactly the best time to wear corduroy, so I remember being miserable during the graduation ceremony itself, but at least I looked better than I felt.

But the best part of graduation came afterward, when a bunch of the kids from my class got together in a “lounge” in the back of a local restaurant for a party. I’d had a boyhood crush on Linda Moore all through elementary school, though I’d been much too shy to ever talk to her about it. I can still picture her now, with her long red hair, pert nose and freckles spreading like stars across the sky of her porcelain-perfect face. She was the smartest girl I’d ever met, and I remember sitting in class and daydreaming about what might happen if I were brave enough to talk to her for hours on end.

Finally, at that graduation party, as my friends and I danced our asses off to “Le Freak” and “YMCA” and “Bad Girls,” I finally worked up the nerve to ask Linda for a slow dance right as the Bee Gees’ “How Deep Is Your Love” began playing. While I may not have been Tony Manero, I felt like I was pretty darn fly for a white guy. It was a magical moment, and it was also the last time Linda and I ever saw each other, as we moved on to different high schools.

Now, as my daughter prepares to take that daunting step from childhood into adolescence, these memories come rushing over me even as I mourn the death of one of my early musical heroes. I look into her eyes and I see the same turbulent mixture of emotions I once felt: The sense of accomplishment from finishing a 6-year journey, the excitement of knowing summer’s just around the corner, the sadness in realizing she won’t be seeing some of her favorite people quite as often, the nervousness of transition and wondering how she’ll find her place in a new environment.

But these changes are not only hers: They’re mine, too. As a parent, raising a child becomes a delicate balance between hand-holding guidance and trustful letting go, and with each of these rites of passage you become more conscious of the fact that you’re one day closer to them walking their own paths. It won’t be too long before my daughter is sneaking into movies and having some shy boy asking her for a slow dance.

As you get older, losing a childhood idol such as Robin Gibb becomes like a gut-check of your own mortality, reminding you of the impermanence of your own own life and the constant change in the Universe. It reminds me that my daughter can’t stay a child forever and, try though I might, I can’t always be by her side to help her through every obstacle life will throw in her path. All I can do is share as much knowledge and wisdom as possible from my own experience, and hope that that gives her a platform from which to launch a life that is so much more than merely “Staying Alive.” –Bret Love

If you enjoyed reading The Bee Gees, Rites of Passage & Staying Alive, you might also like:

Immaturity, Redemption & the Death of Beastie Boys’ Adam Yauch

Bret & Mary- A Love Story (How Green Global Travel Was Born)

Learning The Perils Of A “Work Hard, Play Harder” Life

The Secret I’m Ashamed To Tell You