Exploring Grytviken, South Georgia Island

The Serengeti of the Southern Ocean

(The following is a a guest post by Donna L. Hull, who writes about active travel at My Itchy Travel Feet, The Baby Boomer’s Guide to Travel. You can also follow her on Facebook and Twitter. If you’re a travel blogger interested in guest posting on GGT, please email pitches to Bret Love at info@GreenGlobalTravel.com. We do not accept guest posts from for-profit companies.)

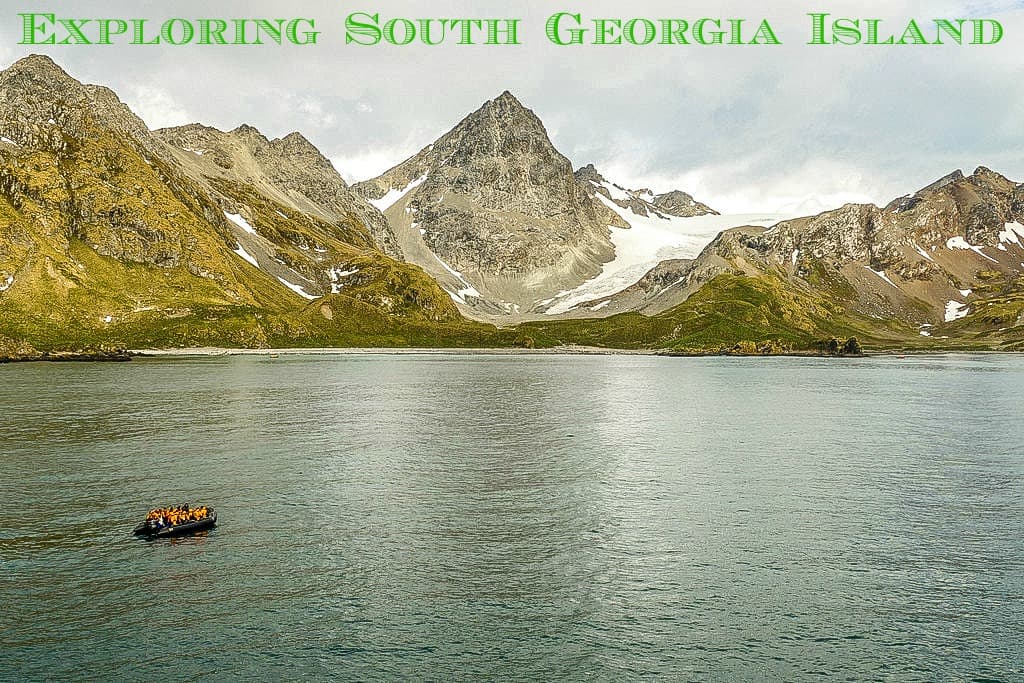

In Cooper Bay on South Georgia Island, a beach teeming with life comes into view as our zodiac approaches the shore.

Baby fur seals cavort near their mothers. Up the beach, two hulking elephant seals sleep off a meal, oblivious to a line of king penguins waddling up and down the trail to a rookery. Sea birds fly overhead intermittently, darting in and out of the waves looking for a meal.

In a nearby cove, kayakers paddle toward a rock for a closer view of the quirky-looking Macaroni penguin, with its orange and yellow eyebrows. I feel as if the ship took a wrong turn and ended up in the wildlife-abundant Serengeti.

Where is South Georgia (and What am I Doing Here)?

I’m on a small ship cruise exploring the sub-Antarctic Island of South Georgia, which is home to over 30 species of breeding birds. To say it feels like the end of the earth is an understatement.

Located in the Southern Atlantic Ocean about 863 miles southeast of the Falkland Islands and 2950 miles from Antarctica, South Georgia can only be reached from the sea. There is no airport— not even an airstrip— on this imposing-looking island studded with glacier-coated mountains.

Some expedition and small cruise ships include South Georgia when sailing to and from the Antarctic Peninsula. But adding the remote island to the itinerary increases the time and expense involved, so only a smattering of travelers step foot on South Georgia each year. I’m one of them.

I’ve been fascinated with South Georgia Island ever since reading Endurance: Shackleton’s Incredible Voyage. The book offers a gripping account of explorer Ernest Shackleton’s 800-mile sail across the Drake Passage from Elephant Island to South Georgia (in little more than a rowboat) in order to save his stranded Antarctic expedition team.

Unlike Shackleton, I don’t have to bushwhack across 22 miles of serrated mountaintops or slide down glaciers to arrive in the protected coves of South Georgia Island’s eastern shores. Shackleton’s journey ended when he walked into the whaling station at Stromness to request help for his shipwrecked crew.

Mine begins by exploring rusted industrial relics in the former whaling station of Grytviken, where the beach and hillsides are littered with the very animals that the whaling industry almost managed to obliterate for good.

Visiting Grytviken, South Georgia Island

The Government of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands, which is part of the British Overseas Territory, administers tourism access for an estimated 50 cruise ships carrying approximately 6,000 passengers that visit each year. Most travelers go to South Georgia Island, with very few ships sailing to the South Sandwich Islands.

Any ship intending to visit, or make landings, beyond Grytviken is required to be a member of the IAATO (International Association of Antarctica Tour Operators). The organization adheres to strict rules set out by the Antarctic Treaty, ideally preventing any type of environmental impact or wildlife disturbance to the Antarctic region.

Although passengers attended a biosecurity inspection as we arrived in Antarctica, an even more thorough check is conducted before entering South Georgia Island. So we bring our boots, walking sticks, parkas, gloves, hats and backpacks for the expedition staff to inspect. Any hint or smudge of dirt is washed away so we don’t import invasive species onto the island.

South Georgia has experience with the damage an invasive species can do: During the island’s sealing and whaling heyday, stowaway rats frequently jumped ship to take up residence. With no natural predators, they proliferated, threatening local bird populations– especially the South Georgia Pipit– by eating their eggs and chicks.

Saving Seabirds from Rodents & Ships

In 2013, the South Georgia Heritage Trust began the SGHT Habit Restoration Project, with the goal of eliminating all invasive rodents from South Georgia Island.

For two years, three helicopters dropped toxic bait pellets across approximately 247,000 acres, whenever South Georgia’s fickle weather permitted. As SGHT Director Sarah Lurcock explained to our cruise passengers, the rats found the pellets to be delicious but most other species did not, which protected them from an unintended eradication.

In 2015, the birth of pipit chicks was documented, proving that nests are being recolonized after years of rodent devastation. The SGHT Habit Restoration Project is considered to be the most successful rodent eradication program in the world. Leaders and scientists from the project are now sharing their knowledge with other islands facing invasive rodent problems.

About a day out from South Georgia Island, our ship’s staff started their measures to protect birds from striking the ship. Exterior lights are turned low and passengers are discouraged from going out on deck after dark. All windows and portholes are covered with blackout drapes or blinds.

During times of poor visibility, the lights of a ship can disorient seabirds. When birds strike the ship, some of them (especially petrels) are not able to fly off the ship. If their feathers become waterlogged, they’ll experience hypothermia.

In addition to the ship’s extraordinary measures to eliminate light, the expedition staff inspects outer areas of the ship each morning to make sure that no bird accidentally landed during the night.

Arriving in Grytviken, South Georgia Island

Passengers arriving in South Georgia Island are not allowed onshore until government officials have cleared the ship once it reaches Grytviken, which is why our first opportunity for exploration is from the water in Cooper Bay.

During the previous night’s pre-dinner expedition briefing, we discussed a cruise up Drygalski Fjord. But strong winds and poor sea conditions limited us to Cooper Bay for the day.

But the wind eventually calms down, allowing each of four color-coded passenger groups about an hour to explore Cooper Bay by zodiac. Guests may also purchase kayak excursions for an extra charge, with around four groups going out each day that the expedition staff is leading those tours.

Discovering a Whaling Ghost Town at Grytviken

Once the ship is cleared in Grytviken, passengers are ferried to shore in zodiacs. At first it’s the Penguins and Seals that attract our attention. A group of molting King Penguins stand like sentries at the edge of the water. They’ll stay this way until their new feathers grow in and it’s safe for them to go back into the water.

The expedition staff has preceded our group, marking out trails with flags and roping. As always, humans are required to maintain distance between themselves and the animals.

On the path leading up to the cemetery where Shackelton is buried, I walk by sleeping Elephant Seals that are so close they could knock me down with a flick of a flipper. Lumpy mounds of tussock grass make the going tough. And you never know when a Seal might be resting in a nearby depression.

After paying homage to Shackleton, I walk back to the trail on the beach. A group of teenage male Elephant Seals alternate between sleeping and practicing adult moves, bumping their chests against each other boisterously. Someday, the one who growls the deepest, rises up the highest, and fights the meanest will become king of his own harem.

Frisky Fur Seals scamper toward the water near The Petrel, a disintegrating whaling ship that rests on shore. Other Seals sleep in the shade of rusting tanks that once held whale oil. Behind it all, the steeple from the Whaler’s Church rises against a mossy green hillside.

Buildings that house government workers and scientists are off limits. But the South Georgia Museum– the former manager’s house– is open, with displays on whaling and natural history and information about South Georgia’s exploration. This is the only place to purchase postcards (which may be mailed from here), books, and souvenirs.

Before boarding a zodiac for the ride back to the ship, I wipe my boots against the bristles of a brush boot cleaner that sits at the edge of the water. When I step back onto the ship’s platform from the zodiac, I turn a complete circle as a crew member power washes my boots and the edges of my waterproof pants.

Visiting the Action at Salisbury Plain

Salisbury Plain is the final stop on our South Georgia Island itinerary. Approximately 500,000 king penguins and breed in the rookery here.

The second largest penguin in the world after the Emperor Penguin, the Kings lay a single egg, which is incubated on their feet under a fold of skin. I’m looking forward to watching the complicated dance as a penguin parent hands off the egg to its mate in order to return to the ocean to feed.

As the captain positions the ship in the Bay of Isles, groups of penguins gracefully arc their bodies in and out of the water. But a steady wind makes going ashore at Salisbury Plain impossible. A zodiac ride to explore near the shore is the new plan for the day. And the ride does not disappoint.

As the raft bounces in the water, the scene looks like spring break on a Florida beach for Seals, Penguins and Seabirds.

A Southern Fur Seal pops its head out of the water to check out the zodiac. A group of Elephant Seals lumber onto the beach in search of a patch of sand. And King Penguins stand in groups by the hundreds. The sounds of barking Fur Seals, the shrieks of King Penguins calling to their mates and the guttural growl of Elephant Seals drift out over crashing waves.

As our visit to Grytviken and South Georgia Island comes to a close, I decide that this truly is the Serengeti of the Southern Ocean– paradise for nature lovers and history buffs alike. –text & photos by Donna L. Hull unless otherwise noted

If you enjoyed our story on exploring Grytviken, you might also like:

How To Get To Antarctica Without Doing the Drake

The Haunting Beauty of Icebergs in Antarctica

Taking the Polar Plunge in Antarctica

Top 5 Eco Attractions in Antarctica