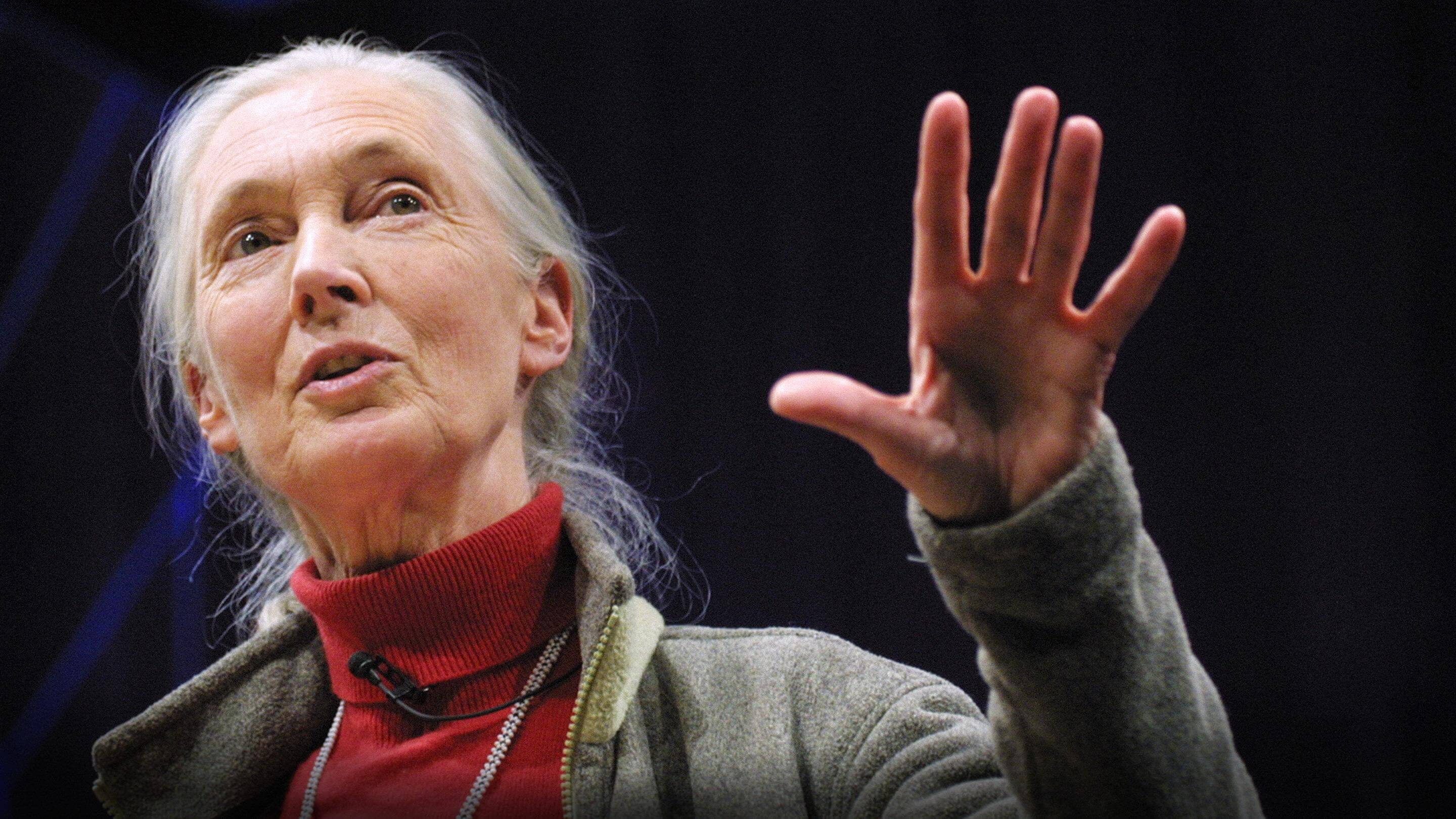

On September 27 of 2011, Jane Goodall launched the documentary film Jane’s Journey with a remarkable one-night-only event designed to give people around the world a rare opportunity to ask questions of the legendary primatologist, wildlife advocate and environmental conservationist.

With special guest appearances from pop culture icons like Angelina Jolie and Dave Matthews, the event (which will be broadcast live via satellite from Los Angeles) will draw further attention to Goodall’s massively influential work, which has changed not only what we understand about the connections between humans and primates, but also how people view our place and responsibility within the natural world.

In anticipation of the event, we were granted a rare opportunity to speak with Goodall about her groundbreaking work in Africa in the ‘60s, the mission of the Jane Goodall Institute and its Roots & Shoots program, and how we as individuals can do our part in preserving our precious planet.

Have you noticed any evolution in the way in which people talk about the relationship between humans and animals?

Since I began in 1960, there has definitely been a change.

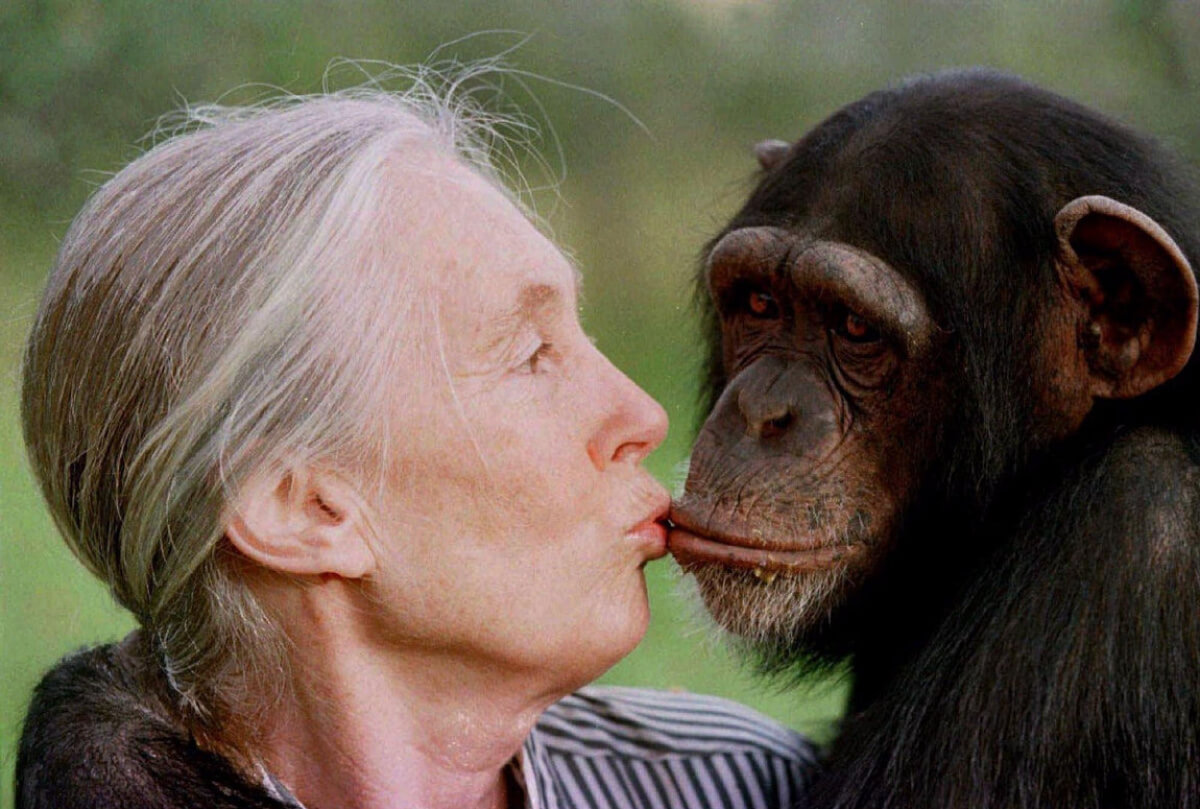

When I first began studying chimpanzees it was not appropriate, especially if you were a scientist, to talk about chimpanzees having personalities or emotions. You couldn’t talk about animals having a mind capable of any kind of thought, because those were unique to us. I shouldn’t have given the chimpanzees names: They should have had numbers.

That attitude is much, much softer now. It still hangs on in certain places– usually where people do rather unpleasant things to animals. They seem to prefer to consider that the animals don’t have feelings.

So there has been a change in understanding, but not often enough does it lead to a change in behavior.

There was initially a lot of controversy over your findings, particularly glorifying the chimps and associating emotions with them. Can you talk about what role gender played in your research?

I think if I had been male, I wouldn’t have been pushing these anthropomorphic ideas. I was told I shouldn’t have given the chimps names, that it is more scientific to number them. I was also told that you shouldn’t talk about their personalities, their minds, or their feelings because those are attributes of our own species.

Fortunately, I was able to think back to the wonderful teacher I had as a child who taught me that animals do have personalities, minds, and feelings, and that was my dog, Rusty. I had the courage of my convictions, and learned how to write in such a way as not to be open to intense criticism from my peers.

In fact, I think my gender helped me. When I began, feminism wasn’t really a concept. Going out into the field as a woman, there wasn’t that urgency most young men felt back then to be the breadwinner. I wasn’t interested in academia. I didn’t want tenure in a university. I wanted to get my PhD because that was the only way I’d get my own [research] money.

In Africa, it was a benefit to be a woman because, in 1961, with their newly acquired independence, the Tanzanians were not very at ease with white males, because white males had lorded over them in the colonies. But they didn’t perceive me as a [threat].

When I first wanted to go to Africa, everybody laughed at me: We didn’t have any money, World War II was raging and Africa was “the Dark Continent,” but most importantly I was a girl. “Jane, get real: Girls don’t do this kind of thing, living with animals in the forest.”

But my mother was a very strong woman, and she used to say, “If you really want something and you work hard, take advantage of opportunity and never give up, you will find a way.” That’s the message I’ve taken to children, particularly girls, all around the world.

How do we get more young people interested in the sciences, particularly animal sciences?

I have to be self-serving here and say let’s get them interested in our Roots and Shoots program. I’ve seen the effect it has on children in helping them to move forward in conservation, meeting other young people who are passionate, and realizing that science doesn’t have to be cold and objective.

It can be very exciting and lead to new ways of interacting with the environment, animals and each other, too. The Roots and Shoots program is in 126 countries, with children coming together (especially on the Internet) and discussing all that they do. It’s hands-on, roll up your sleeves, get out there, choose a program and take action knowing that every single day you can make a difference.

In the next 20 years, what do you see making the biggest difference for chimps in areas where they are coming into conflict with people in Africa?

This is a situation in which the Jane Goodall Institute has been extremely involved.

I flew over Gombe National Park in the early ‘90s and was shocked to see that, outside the boundaries of this tiny park, the deforestation left totally bare hills. There were more people living there than the land could support, and they were cutting down the last trees to grow crops, to raise goats, or for charcoal. How could we even try to save the chimpanzees while the people were struggling to survive?

That led to our TACARE (Take Care) program, which is a holistic effort to help people improve their lives with new farming methods, protecting the watershed, scholarships to keep girls in school, better healthcare. We’re especially working with women because, all around the world, as women’s education improves, family size drops.

After about seven years of this program, the villagers set aside land for conservation as a buffer all around Gombe Stream National Park. It’s been so successful that we are now replicating this in different parts of Africa around other wilderness areas, to have people become partners in conservation.

What are the most valuable lessons that humans can learn from chimpanzees and other primates?

There are various lessons. One lesson the chimpanzees in particular have taught us is that we are definitely part of the animal kingdom. The similarities– the fact that we differ genetically by just over 1%, the blood and immune system are almost the same, the anatomy of the brain…

Hopefully some people, eventually, will change the way we deal with animals. More specifically, I learned the tremendous importance of early experience in the life of a chimpanzee. Good mothers, bad mothers, traumatic experiences in the first few years, it really does make a difference in adult behavior.

Of course, child psychiatrists/psychologists today are emphasizing that this is true for human infants. But it’s easier to trace the affect of trauma in early life in a chimpanzee, because it doesn’t try to conceal his or her feelings, than it is for a human that tries to behave in an accepted way.

What do you see as the biggest global challenges to wildlife conservation?

Overall, it’s the human population growth that is an underlying threat to wildlife conservation.

The effect of our reckless burning of fossil fuel and heavy meat-eating, which leads to methane production and destruction of forests in order to provide grazing lands or grow grain, and a waste of water.

This is having a tremendous impact, with climate change and global warming. The numbers of tornadoes, hurricanes, floods and drought is definitely affecting wildlife all around the world today. There is abject poverty, and if you’re really poor you’ll destroy the last little bits of the environment to grow food or exploit those resources in order to make money to raise your family.

Then there’s the unsustainable lifestyle the rest of us have: Most of us have way more than we need, and very often more than we even want.

What can we as average citizens do in our everyday lives to confront these issues, especially when so much of it seems tied up in political wrangling?

We have to start off with ourselves. Each of us makes an impact on this world every single day, and we can choose. We can think about the consequences of what we eat, what we wear, where it comes from, did it involve child slave labor, how far has it come… all these kinds of questions.

When it comes to addressing the politics, that’s going to differ enormously. People tend to point fingers: It’s the fault of the politicians, or the scientists, or big business. Let’s see where we as individuals fit into this.

Do we lobby our politicians sufficiently when they do things we don’t like? More importantly, do we thank them and support them when they make tough decisions on behalf of the environment, or do we decide that’s hurting my lifestyle so I’m not going to support that person anymore?

We criticize corporations for being environmentally destructive. But as long as we’re buying their products, we have no leg to stand on. We have to realize that each one of us does have a responsibility in our own lives. –Bret Love

If you enjoyed reading our Jane Goodall interview, you might also like:

INTERVIEW: Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund CEO Tara Stoinski

INTERVIEW: Lek Chailert of Elephant Nature Park & Save Elephant Foundation

INTERVIEW: Jill Robinson Fights To Save Wildlife Via Animals Asia Foundation

INTERVIEW: Defenders Of Wildlife Wolf Conservation Expert Suzanne Stone

INTERVIEW: Wildlife Expert/TV Host Jeff Corwin