I’ve never been so happy to depart a destination as I was the day we left Tanzania’s Lake Natron to visit the Maasai people in a traditional village.

Wrecked by a stomach virus, relentless heat, and winds that pelted us with stinging sand, I was miserable and ready for pampering at Lake Manyara’s Escarpment Luxury Lodge.

But it’s our time with the warm, welcoming Maasai villagers that I’ll forever remember most about that day.

There were no signs pointing travelers to the unnamed village, which is located about 10 minutes outside Mto Wa Mbu en route from the Ngorongoro Conservation Area to Lake Manyara National Park. In fact, even calling it a village might be a bit of a stretch.

There were perhaps a dozen small circular bomba (houses) made from grass, mud, sticks, and cow dung, all enclosed inside a circular fence (enkang) fashioned from thorned Acacia branches.

The surrounding scenery was dry and desolate, with dust devils swirling across the horizon.

But from the moment the Maasai villagers came walking out to greet us, singing a song of jubilant welcome that hit me square in my soul, I felt my mood being lifted for the first time in days.

And by the time we left and made our way to Lake Manyara, I realized that my face hurt from smiling so much…

READ MORE: Ngorongoro Conservation Area

The Maasai People: An Introduction

Wherever you go on the East African safari circuit of southern Kenya and northern Tanzania, the Maasai are a near-constant presence. The number of Maasai in Kenya is estimated to be approximately 800,000, with about the same number living in Tanzania.

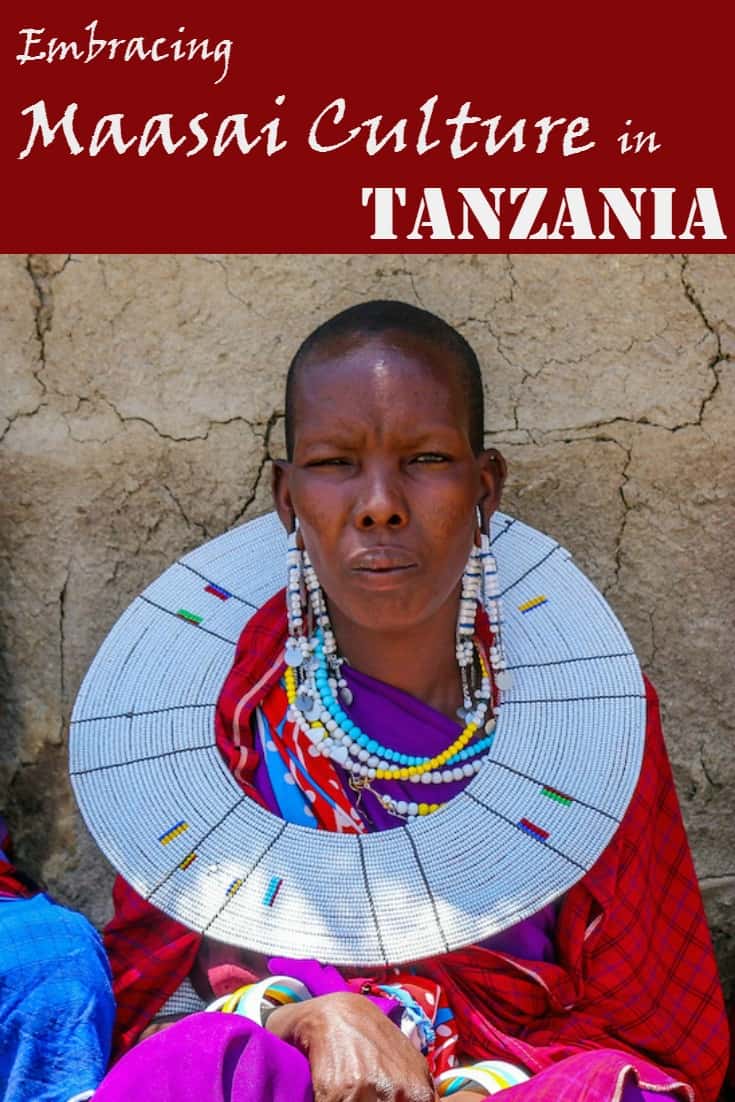

You’ll spot the brightly colored reds, blues and purples of their shúka (sheets worn wrapped around the body, with one over each shoulder and a third over the top of them) standing out vividly against the landscape.

You’ll see them standing tall and proud alongside the road in small villages such as the one we visited, modern towns such as Arusha, and walking across the vast open pastures on which they continue to graze their cattle, as they have for more than 500 years now.

While it may be the world-renowned wildlife that draws most travelers to Tanzania, it’s the Maasai people who give the region its distinctive cultural flavor. Meeting the Maasai and getting to know more about their life in the savannah is an integral part of the East African travel experience.

So it’s worth learning more about these semi-nomadic pastoralists before you visit.

READ MORE: Exploring Magical Tarangire National Park

Maasai History: A Brief Overview

The Maasai are a Nilotic people indigenous to the African Great Lakes region, with roots that can be traced back to South Sudan. Their language, Maa, includes idioms still spoken in Ethiopia and Sudan today.

According to their oral history, they began migrating south from the lower Nile Valley north of Kenya’s Lake Turkana sometime in the 15th century. They ultimately arrived in their current range between the 17th and late 18th century.

Many of the ethnic groups that had established settlements in the area were either displaced or assimilated by the Maasai. The newcomers also adopted certain customs from them, including ritual circumcision and a social organization focused more on age than descent.

By the mid-19th century Maasai territory included the entire Great Rift Valley as well as the lands that surrounded it. The Maasai soon became as well-known for their strength as hunters and warriors (using spears, shields, and clubs that could be thrown accurately from up to 70 paces) as they were for their cattle-herding.

The dark period between 1883 and 1902 is known as emutai, meaning to wipe out. It’s estimated that some 60% of the total Maasai population lost their lives during this period as a result of smallpox, drought, and starvation (after a disease known as rinderpest killed most of their cattle).

In the 20th century, vast sections of Maasai land were taken from them and turned into national parks and wildlife reserves. The government also pressured the Maasai to abandon their semi-nomadic lifestyle in favor of farming and a more sedentary life. You can understand why the locals were not pleased: They’ve been fighting to reclaim their lands and preserve their traditional way of life ever since.

READ MORE: Preventing Gender-Based Violence in Tanzania

Embracing Maasai Culture

According to our Tanzania Journeys guide, Rama Mmasa, the village we visited was relatively new to welcoming travelers. So our time there felt less like an organized tour and more like being welcomed into a new friend’s home.

They greeted us with the traditional polyphonic music of the Maasai people. A leader (called the olaranyani) sang the rousing melody while females sang harmony on call-and-response vocals, (known as namba). The males made guttural throat-singing sounds to provide rhythmic syncopation.

All of them were tall and lean, with shaved heads and gorgeous skin the shade of fine dark chocolate. They were all dressed in vivid shùkà, whose color varies according to age and gender. Older men usually wear red wraparounds, whereas women usually opt for checked, striped, or patterned pieces of cloth.

The women were all festooned with exceptional beadwork, through which they express their position in the society. Once made of natural materials such as clay, shells, and ivory, now they use colorful glass beads, which allow for more detailed designs. Each color used has a meaning: White symbolizes peace, blue is the color of water, and red is the symbol of warriors and bravery.

When Maasai warriors come of age, the ceremony (known as eunoto) involves 10+ days of singing, dancing, and rituals, including the competitive jumping for which the Maasai are known.

The celebration of our arrival was much shorter, but no less exuberant. Within five minutes, we were brought into a semicircle to dance with them (see our YouTube video above).

READ MORE: Climbing Mt Kilimanjaro

Jumping Into the Circle

Since many of the villagers did not speak English, a local man named Daniel served as our guide. He explained that the Maasai’s jumping form of dance, known as adumu or aigus, is traditionally carried out by warriors.

The men form a semicircle and take turns at the center, jumping as high as possible without letting their heels touch the ground. As each warrior takes his turn to jump, the others sing a high-pitched song whose tone depends on the height of the jump.

While the ladies performed a more demure dance and the younger men showed off their formidable jumping prowess, Daniel gave me a few basic instructions and a Maasai staff to hold onto. Then it was our turn to enter the circle.

I’m highly competitive by nature, so I was determined to make a decent showing. Despite my 250-pound frame, I managed to match Daniel jump-for-jump the first few times. But by the end my “verts” were becoming decidedly more horizontal.

Still, my efforts were earnest enough that the men all smiled and shook my hand enthusiastically. Through body language, it was easy to see that there was mutual respect there– from us for the richness of Maasai culture, and from them for our eagerness to participate in it.

READ MORE: 7 Cultural Practices Tourists Shouldn’t Support

Inside A Maasai Hut

When the dancing was over, Daniel invited us inside a hut to learn more about Maasai culture and customs. Teenage girls Gladys (in blue) and Anna (in purple) tagged along, welcoming a chance to practice their English. The home was small and spartan, with a large sleeping area for the male, a smaller one for his wife and children, and a cow dung fire for cooking.

Daniel explained that the Maasai people have a patriarchal social structure. A council of elder men oversees the daily running of the village and govern matters using an oral body of law. Execution and slavery are unknown in Maasai society, and arguments are usually settled via cattle payment. The number of cattle and children a man has determining his wealth.

Maasai men often have several wives, each with her own house, but the women must build their own houses every five years due to termites. Boys are expected to shepherd the family’s cattle (which provides their 3 main food sources: meat, milk and blood). Girls help their mothers gather firewood, cook and handle most of the family’s other domestic responsibilities.

Many Maasai villages are polygamous. When a woman marries, she doesn’t just marry her husband, but his entire age group. Traditionally, a Maasai man was expected to give up his bed to a visiting male guest. This custom has become much less widely practiced in recent years. But it’s not uncommon for the woman of the house to join the guest in bed, if she desires.

The Maasai belief system is monotheistic. The deity is called Engai and can be both benevolent and vengeful. The most important figure in the Maasai religion is the laibon, who is part priest and part shaman. The laibon’s role traditionally includes healing, divination and prophecy. Nowadays, they also serve a political function in the community, as most belong to the elders council.

Meeting the Moran

Both sexes of the Maasai people have historically undergone a ritual circumcision known as emorata. This controversial practice is gradually waning due to increasing criticism from Maasai activists and foreigners alike.

Adolescent boys who undergo the procedure (which is performed without anesthetic, using a very sharp knife) before becoming warriors are expected to do so in silence. Crying out in pain brings great dishonor to the family.

Afterwards they are known as Moran (or il-murran). A new group of soldiers is initiated every 15 years or so, chosen among young men ages 12 to 25. After the initiation ritual, they are sent to live in a manyatta (or village) built by their mothers for many months, during which they make the transition to becoming warriors.

You’ll see many Moran alongside the roads in Kenya and Tanzania, with their distinctive white facial markings, offering to pose for tourist photos for money.

When we asked Rama if this practice was frowned upon by Maasai elders, he explained that this was basically the only way these boys can support themselves during their transition to adulthood.

READ MORE: Serengeti National Park Wildlife Safari

Threats to the Maasai Way of Life

Problems between the Maasai people and government authorities date back more than 100 years. A pair of treaties with the British government reduced Maasai land in Kenya by 60% to make room for ranches for colonial settlers.

In Tanzania in the 1940s, the pastoralists were displaced from the fertile lands around Mount Meru, Mount Kilimanjaro and the Ngorongoro Crater.

Much of the land taken from the Maasai was used to create many of the world’s most famous wildlife reserves and national parks. These include Kenya’s Amboseli, Masai Mara, Samburu and Tsavo, and Tanzania’s Lake Manyara, Ngorongoro, Tarangire and Serengeti.

More recently, the Maasai have resisted the urgings of the Kenyan and Tanzanian governments to adopt a more sedentary lifestyle and send their children to government-approved educational facilities.

According to Rama, this is because the Maasai believe that most people go to school to learn how to become rich, and they believe that they are already wealthy due to the richness of the Maasai culture and lifestyle.

Non-profit organizations such as Survival International are currently working with tribal leaders to help the Maasai regain grazing rights to their historic lands and resist government efforts to force them to adapt to modern notions of “progress.”

With more than 1 million Maasai estimated to live in these popular ecotourism hotspots, here’s hoping their rich, distinctive culture and lifestyle continues to thrive for many centuries to come.

READ MORE: The Battle Over Maasai Land Rights

A Chance to Support the Maasai

Wherever we travel, we always buy souvenirs directly from local artists and craftsmen to help them earn a decent living.

Now that we’ve launched our Green Global Travel Fair Trade Boutique, we’re selling some of those souvenirs and using the profits to give back to conserve indigenous nature/wildlife and culture around the world.

Gladys, the young woman mentioned above, is very interested in pursuing a higher education and hopes to be a teacher someday. But in Tanzania families must pay for education beyond 9th grade, at a cost of around $300 US per year.

We’re selling some of the bracelets and necklaces we bought from the Maasai as part of our Private Collection. We hope to send some of that money to Gladys, which will help to fund her education.

We hope you’ll stop by our boutique and purchase a piece of Maasai culture, and help us help an intelligent young woman who’s keen on preserving that culture for many generations to come! –Bret Love; photos by Bret Love & Mary Gabbett

Our trip to Tanzania was sponsored in part by Adventure Life and Tanzania Journeys, with clothing provided by ExOfficio. But we will never compromise our integrity at the expense of our readers. Our opinions remain our own.