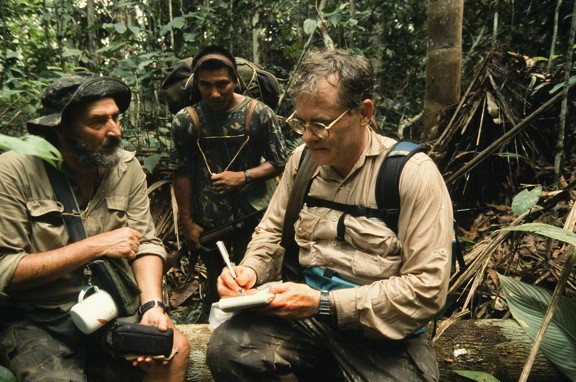

NatGeo’s Scott Wallace

On The Expedition To Save Uncontacted Amazon Tribes

There are shockingly few regions of the world left relatively untouched by human “progress.” One of them– Brazil’s Amazon rainforest– is increasingly being threatened by development interests, with a bill currently before the Brazilian congress that would revise the nation’s long-standing forest protection code to allow for more agriculture and cattle ranching.

It’s serendipitous, then, that Scott Wallace’s new book The Unconquered: In Search of The Amazon’s Last Uncontacted Tribes has been released. The story follows a National Geographic assignment that put Wallace on a research team trekking into the Amazon’s deepest recesses, gathering information that will hopefully help protect the mysterious tribe known as the People of the Arrow, one of the region’s last uncontacted tribes.

It’s an amazing story– part Indiana Jones adventure, part personality profile of expedition leader Sydney Possuelo, a noted Brazilian Indian Rights activist– and we recently spoke with Wallace about the extraordinary experience.

In the book, you mention your extensive journalism experience in the Amazon. What initially fascinated you about the region?

I took a year off from college and worked as a literacy instructor among Amazonian native tribes back when I was 20 years old. There was rawness to the Amazon in its enormity, wildness, and untamed frontier of it. I found it fascinating. The existence of native tribes, the sweep of its rivers, the sense that you’re in a tropical version of what North America must have been like 200 or 300 years ago.

Your personal life was clearly in shambles when you got the call from National Geographic that led to this book. What was your motivation for taking the assignment?

I’m a journalist, so I got into this field to do exactly this kind of thing– to go where few other people get to go to look deeply into an issue and to bring to bear the full range of my skills and writing abilities. This was a unique opportunity that almost no one gets to do- the fact that we were going into the most remote Amazon, into the territory of an un-contacted tribe– was too compelling of a prospect to say no to.

Did you or anyone else from the expedition have conflicting feelings about the potential impact your journey could have on the People of the Arrow?

The work of the Department of Isolated Indians, which was running the expedition, requires a certain amount of risk taking in order to complete the mission. The greater good is to protect these un-contacted tribes; the risk is that something could go wrong while you are doing it. There could be inadvertent contact, or a violent clash. The work is absolutely necessary, because without it you can’t prove the Indians are on that land and you can’t get the legal protection required to make sure that rainforest is going to remain intact. I would have to say also that our impact was pretty minimal. We were cleaning up after ourselves and all the construction– creating lean-tos and other structures– was made strictly from materials right there in the forest that biodegrade with time.

How would you describe your emotions as you set off into the jungle?

The first couple weeks of the journey were on these boats moving up river. It was two weeks after I joined the expedition that we actually left those boats behind and set forth into the deep jungle by foot. Certainly, it was frightening in a way except that I was with 34 expert woodsmen. I wouldn’t have wanted to wander more than 20 yards into that forest alone for very long. There was excitement about going into a completely wild area that has never seen outsiders, but on the other hand there were a great many hazards at every turn. You had to be incredibly alert and you couldn’t be careless about any step that you took. It was a draining experience, but it was an exciting and exhilarating trip.

For readers who aren’t familiar with Sydney Possuelo, why is he such a big deal in Brazil?

Sydney Possuelo is one of the most renowned wilderness explorers in modern Brazilian history, and also an Indian rights activist. He is a Brazilian government wilderness scout and he led a seat change in Brazil’s policy towards its uncontacted indigenous groups. He led a sea change in the policy from going out and contacting those Indians to saving them from that and protecting the lands that they are on by stopping the advance of the frontier. It’s a huge shift that he engineered. He was also the leader of our expedition and the main character of my book.

In what ways would you say the survival of the People of the Arrow and the health of the Amazon are ultimately connected?

The People of the Arrow are one of 26 un-contacted tribes and all of them depend on healthy, pristine rainforest for their survival. They have no need for anything from our society if they have the pristine rainforest environment from which they derive their livelihood. This is an instance where their survival and respect for their self-determination to be left alone is absolutely in line with environmental conservation, preservation and protection of the rainforest. They cannot survive without that rainforest being intact, unpolluted, with its bounty of animals, fish, and all the living species. In Brazil, there are 55,000 sq miles of virgin primeval forest that’s being protected because there are un-contacted tribes there. They are in effect helping us in as much as the rainforest to protect the global climate. Their survival is also our survival.

Do you think tribes like the People of the Arrow ultimately have a chance of remaining unassimilated?

Yes, I think they do if enough people stand up and support those that are defending them. Perhaps one of the most important things about this book besides being a pleasurable read, I think it also serves to highlight this very important issue. If there are enough people aware of this issue and if those in Brazil who are implementing and carrying out the policy get the recognition from a global audience who are keeping their eyes on what is happening in the rainforest, then the policy can succeed.

What organizations are working to save the region?

Amazon Watch, Survival International and the forest campaign at Greenpeace are all very good organizations that are helping to not only to defend the rainforest, but are also working to help indigenous tribes in their efforts to preserve their forest and defend it from those who would destroy it for profit.

How did this experience change you as a person?

I think it made me a lot more aware of the fact that there is another world beyond this one of shopping malls, cell phones and pre-packaged food. There is another way to live. It’s the way our species has lived for 99% of its history, and I feel like it has brought me closer to our human and animal origins. –Bret Love

If you enjoyed our interview with Scott Wallace on the Uncontacted Amazon Tribes, you might also like:

Peruvian Amazon- Piranha Fishing

Peruvian Amazon- Birds & Monkeys

Peruvian Amazon- Sloths & Dolphins

Peruvian Amazon- South American Manatee

Peruvian Amazon- Shaman & Ribereños Village

Peruvian Amazon- Into the Jungle