Joan Embery on

Why Zoos are Good for Conservation

Keeping wildlife in captivity is bad. Animals being free to roam the wild is good. Right?

The issues surrounding animal rights can seem very black and white to armchair activists. But what happens when the habitats in which these animals live– their food sources, their safe havens– are destroyed? What happens when humans hunt and poach animals to the brink of extinction? How do we save these species for future generations?

For better or worse, most kids first learn about wildlife from their local zoo. The very best zoos not only focus on wildlife education, but conservation of endangered species via captive breeding and responsible re-introduction programs:

- The Phoenix Zoo helped bring the Arabian Oryx back: Extinct in the wild in 1972, there are now more than 1,000 roaming freely.

- Critically endangered by loss of their Brazilian rainforest habitat, the Golden Lion Tamarin‘s status has been improved by captive breeding at DC’s National Zoo.

- There were only 22 California Condors left in the wild by the late 1980s. The San Diego Zoo used condor hand puppets to feed baby birds, and now more than 200 fly free.

- Colorado’s Cheyenne Mountain Zoo has used artificial insemination to breed and release over 200 Black-Footed Ferrets, which were mostly extinct in the wild by 1980.

- Only 45 Amur Leopards remain in the wild, but there are 220 in breeding programs in zoos around the world, with a reintroduction scheme currently in the planning stages.

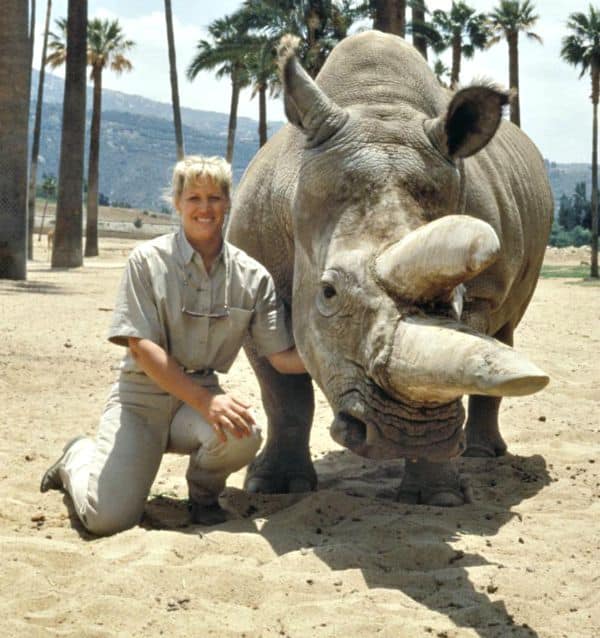

Joan Embery is one of the world’s leading wildlife conservation advocates. A professional Fellow of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, she founded the American Association of Zoo Keepers. As the San Diego Zoo’s goodwill ambassador since the early 1970s, she’s appeared on The Tonight Show nearly 50 times and hosted educational shows such as Animal Express, Animals of Africa and myriad PBS specials.

We recently spoke to Embery about breaking into the male-dominated world of veterinary medicine in the late ‘ 60s, what drew her to wildlife education, why zoos are good for conservation , and the role she sees ecotourism having in saving endangered species.

READ MORE: Inspirational Animal Rights Activists (15 Female Heroes)

When did you first fall in love with wildlife?

From my earliest recollection, I was drawn to animals. As a child growing up, I spent summers with my uncle in Santa Cruz. He was a veterinarian and did large animal work. That was my early inspiration to go to vet school.

I was ahead of my time: On my first tour up at UC Davis, I found out there was only one woman in the class, because the career was not really open to women then. Now, over two-thirds of most veterinary programs are women.

How did that lead to what you do now?

In an attempt to prove my capabilities with animals, I applied at the San Diego Zoo in my first year of college. The only position available to women was working in the children’s zoo and hand-rearing young wild animals.

Eventually the zoo developed a spokesperson job to represent the zoological society in the process of building a wild animal park, and they wanted a female ambassador. Over 600 people applied, and the PR Director gave it to a model with no animal experience, which proved to be a problem.

Once the zoo leadership changed, I got the position. Within a year we were on The Tonight Show.

When did you come to realize the connection between animals and the health of the environment in which they live?

In my early years, I trained elephants. Elephants are endangered, poached and under extreme pressure because they need large landscapes and require forage and water. They can be destructive in close proximity to people.

Working with animals, it’s not long before you realize that the thing you love most has some serious challenges for the future.

As I transitioned into conservation education and started traveling all over the world, I realized these animals that have existed for eons are seeing a rapid decline in numbers and being impacted by growing human populations, competition with livestock, deforestation, political instability, pollution, disease, etc.

READ MORE: 50 Interesting Facts About Elephants (for World Elephant Day)

Was there an eye-opening moment that made you passionate about getting more involved in conservation?

In countries like Madasgascar, 85% of the forest habitat has been cut and they have the highest number of endemic species on the planet. It’s scary because the birds, reptiles and other animals are their natural resources. This is their future, and they’re unknowingly cutting off their lifeline.

There’s a direct correlation: When population rises, wildlife and resources decline. At some point, you have to find sustainability. People who are economically challenged look at natural resources as an immediate fix. But the long-term is disastrous for wildlife, plants, and ultimately the human populations that rely on those resources.

When you cut the forest to start agriculture, you have erosion and mess up your wetlands and offshore reefs. It’s not something we can ever replace.

What role do you see responsibly managed zoos having in the conservation of species being eliminated in the wild by habitat destruction and poaching?

The #1 role of zoos is education– introducing people to wildlife.

Only 1% of our population is able to spend $8,000-$10,000 to fly around the world and hike for four hours up a muddy mountain to see gorillas in the wild. How many people are going to see a lion or an elephant in the wild on the Serengeti plains?

Yes, we have TV and movies, but that’s only a window and sometimes it’s unrealistic the way nature is being showcased for ratings. Our natural world is misrepresented, and not as respected as it should be.

What role do you see responsible ecotourism playing in conservation?

If it’s properly managed, I see ecotourism having a huge positive effect. People become ambassadors for nature when they come home, show their pictures and talk about their experiences. For many countries, it’s a major source of revenue, giving value to the resources we want to protect.

Any examples you can mention where that approach has been particularly effective?

It’s been proven with Rwanda’s mountain gorillas: I don’t think Dian Fossey really wanted people coming into her gorilla habitat, but she realized people would be their salvation.

Until the tourism market was built to see gorillas in the wild, their greatest value was to be poached. Now tourism has provided a major source of revenue to Rwanda. All of a sudden these gorillas became incredibly valuable alive, because people were paying big dollars to see them. It put Rwanda on the map.

Now people from all over the world have been to Rwanda and seen the gorillas. They have such a strong connection that they want to support efforts to conserve the gorillas. Now, if Rwanda ever steps out of line with the gorillas, there is this whole constituency of people who feel connected to those animals and will stand up for them.

Can you tell me about your ranch and what your mission is?

My mission is conservation education. We have high school and college students come to the ranch and learn how to be zookeepers and wildlife managers. We teach them about permits, keeping daily records, feeding, treatment with veterinary care and assessments, and animal handling skills.

As they learn, they become presenters, and some volunteers are eventually hired for jobs. My very first intern is now my ranch veterinarian. I do programs for the Western State Parks Conference, serving as keynote speaker for people who work in resource management and interpretation. I also give wildlife education presentations for corporate groups, educational groups and community groups.

How many animals do you have on the ranch now?

We generally keep about 30 wildlife ambassadors, all trained to be presented on stage and each carrying with them various messages.

If I bring a Toucan, I’m talking about the challenges to the Amazon Rainforest. If I’m talking about Cheetahs, poaching might come into play. With my 16-foot Burmese Python, I’m talking about invasive species and the impact Pythons from the pet trade have had on the Everglades and native wildlife there. When we had a Mountain Lion, I talked about they exist in our local area and come into our backyards.

I also have my own non-profit institute, and we’ve supported Mountain Lion education and outreach. I use these animals as a catalyst to develop a connection with people who are interested in animals by telling stories and relating conservation principals. -by Bret Love

If you enjoyed our interview on Why Zoos Are Good for Conservation, you might also like:

INTERVIEW: Jeff Corwin On His New Show & Challenges Facing Wildlife Conservation

INTERVIEW: NatGeo’s Dereck Joubert on Rhinos Without Borders

INTERVIEW: Dr M Sanjayan on PBS’s EARTH A New Wild

INTERVIEW: Marine Conservationist Guy Harvey

INTERVIEW: TIES Founder Megan Epler Wood on the Evolution & Future of Ecotourism