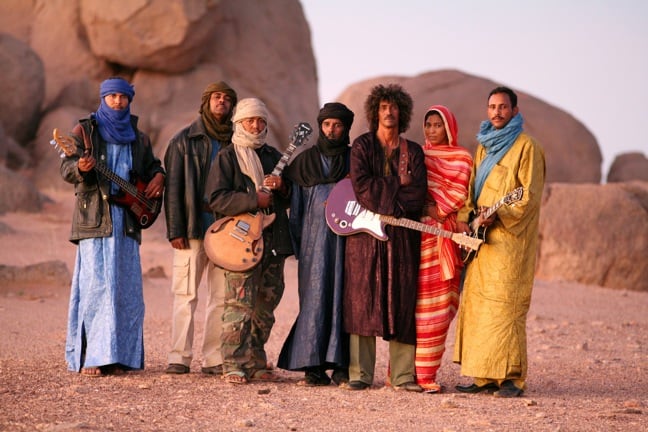

Tinariwen, Mali’s Tuareg Blues Legends

The African blues legends of Tinariwen have an incredible back-story that speaks to the importance of patience and persistence on the path to success, particularly in times of crisis. Formed in 1979 by musicians born in the Sahara Desert of northern Mali, the ensemble came together in Algerian refugee camps, where they lived to escape persecution after the Tuareg rebellion of 1962-64.

Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, who witnessed the execution of his father (a Tuareg rebel) at age four and later made his first guitar from a tin can, a stick, and bicycle brake wire, founded the band. Radical protest songs from Morocco, Algerian rai, and classic rock artists such as Led Zeppelin and Jimi Hendrix influenced their music, but they started out playing weddings and baptisms. Locals called them Kel Tinariwen, which loosely translates from the Tamasheq language as “the People of the Desert.”

In 1980, Libyan leader Muammar al-Gaddafi enlisted Tuareg men to receive military training, and Ag Alhabib and Co. heeded the call. In 1985 they did the same for Tuareg rebels, and ultimately met up with other musicians who would join the band. Tinariwen began writing songs about the sociopolitical issues facing their people, recording them onto cassettes for free for anyone who wanted one. Their “Desert Blues” sound began to spread by word-of-mouth, giving voice to the problems of the Tuareg people.

Then, after returning to Mali for the first time in 26 years, the second Tuareg rebellion of 1990 sent Ag Alhabib and his friends back to fighting for their lives and freedom.

Finally in 2001, with help from French world music group Lo’Jo, Tinariwen performed high profile gigs at the WOMAD and Roskilde music festivals, and released their first album outside of North Africa. They gradually attracted influential fans such as Bono and the Edge of U2, Thom Yorke of Radiohead, and Chris Martin of Coldplay. In 2005 they received a BBC Award for World Music, and in 2010 they represented Algeria in the opening ceremony of the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa.

Now, more than 30 years after the band’s formation, Tinariwen is coming off a Best World Music Album Grammy Award for their 2011 album, Tassili. But that doesn’t mean that things have gotten any easier for the group, as the armed conflict that has plagued Northern Mali ever since its independence from France in 1960 continues unabated.

The militant Islamist group Ansar Dine, led by Iyad Ag Ghaly (who took a leading role in the Tuareg rebellion of 1990, and is suspected to have al-Qaeda ties), is fighting to impose strict Sharia law throughout Mali. After Ansar Dine declared “We do not want Satan’s music,” Abdallah Ag Lamida was arrested by radical Islamists last year while trying to save his guitars from being destroyed.

As a result of the political unrest in Mali, the nomads of Tinariwen had to make an epic journey to the desert of Joshua Tree, California to record its critically acclaimed new album, Emmaar. Boasting guest appearances by Red Hot Chili Peppers guitarist Josh Klinghoffer, Nashville fiddler Fats Kaplin, and poet Saul Williams, the album is a gritty, atmospheric and hypnotic work that cements Tinariwen’s status as leaders of the African blues revolution.

We recently spoke via translator with vocalist/multi-instrumentalist Eyadou Ag Leche, who joined the band back in the ‘90s, to discuss everything from the essence of Tuareg culture to the deep historical connections between the music of West Africa, the Delta Blues, and Rock ‘n’ Roll.

For our readers who may not know much about the Tuareg, how would you describe the culture? Could you talk about the importance music plays in everyday life?

The essence of the Tuareg culture is closely linked to the desert, and our environment. Our culture is a matriarchal society, so the women have a leading place in our community. Music and ancestral Tamasheq (our language) poetry is absolutely a part of the everyday lives of the Tuareg. We play a lot of traditional music, like the Tende, a style and rhythm inspired by the camel’s dance. Percussion, women singing, and Tamasheq poetry are the essence of Tuareg music, and definitely part of Tinariwen’s sounds.

How did Tinariwen originally come together as a band?

The first members were Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, Abdallah Ag Lamida, Hassan Ag Touhami, “Japonais,” and Keddou Ag Ossad. They began playing together around Tamanrasset in southern Algeria, performing for baptisms and weddings. The songs were about life in the desert and love, but also closely linked to the sociopolitical situation of our Tuareg community– the suffering and rights of our people, who were forced into exile. When the Tuareg rebellion broke out in Mali, the songs helped to spread the message about our cause. Tinariwen has always been a collective, and new members joined the band over the years. Today, Tinariwen is constituted of 4 generations with the arrival of Sadam, our youngest guitarist and singer.

What were some sociopolitical issues of the Tuareg rebellion that this music was created to address?

Since decolonization and the borders that were imposed on us by France, we never got help from the Malian government for essential infrastructure, such as health, education, and water. This forced our people into exile and caused chaos. We want to spread the message that our community is only wishing for recognition of its rights, and that we want freedom and peace at home. This is mostly what we sing about when we’re addressing a message about our cause.

When the band was first starting out, distributing homemade cassettes throughout the Sahara region, did you ever dream of the success the band enjoys today?

No, we couldn’t imagine achieving such international success from our desert! We are very grateful to all the audiences we meet around the world. But as musicians our original aspiration was simply playing, enjoying, and sharing our music. Another important part is to spread the message of our community’s suffering, and this simple claim for peace and rights.

Tinariwen has performed all over the world. Can you talk about your favorite countries you’ve been able to travel to?

We love discovering other natural environments, and particularly other deserts in the world. Our favorite country remains home! But we liked the awesome nature of Chile, where we traveled in January, and we really enjoyed the desert of Joshua Tree, where we recorded our album. Lapland was great also, because we met nomads from the extreme north of the planet. As long as we can feel the strength of nature, the elements, the silence, we feel good.

There is a deep historical connection between the music of West Africa and the Delta blues. But I’ve read that you’d never heard American blues music until you began touring internationally. Can you talk about that connection?

Yes, we have the same feeling. Like the blues, our music is about nostalgia. We call our nostalgia Assouf. Like the blues, we sing about missing our people, our home, love and exile. We discovered blues not long time ago, and most of our members listen to blues a lot now.

One of the first things the al-Qaeda militants did after invading Mali was to condemn “Satan’s music” and destroy people’s instruments. Why do they see the music of Mali as such a threat?

These people are against cultures and freedom in general. There is no reasonable explanation for such a hatred-fueled behavior, I would say.

I’ve read that Abdallah Ag Lamida was arrested by Ansar Dine militants while trying to rescue his guitars. How did all that go down?

He lost his guitar, but he managed to escape after few days. He has been arrested by the Mujao, but it was not because of his guitar.

Due to the political instability of Mali, you had to record the new album in Joshua Tree. How did that change of scenery, and working with western producers, impact the band’s sound on Emmaar?

Emmaar is the first album that we recorded far from home. We couldn’t record in our territory, as the situation was too unsafe. But we needed to record it in another desert, because it’s an environment that is essential for us. We need to feel the natural elements of it– the sand, the silence, the air, the wind, the rocks– and the feeling of freedom. We decided to record in Joshua Tree, and we felt at ease. We recorded the album live, all together in the same room, to feel the interconnection between each other, the words and the music. We wanted to get the rough, organic sound of our first album, Radio Tisdas. And thanks to good gear, we were able to get that sound!

I know the Tuareg typically live a nomadic lifestyle. But when you’re traveling on tour, what do you miss most when you’re away from your homeland?

We always miss our homeland. We miss the desert. We miss our people. We’re traveling non-stop with them in our mind!

Mali and other parts of north Africa seem to have had more than their fair share of turmoil in recent years. What are your hopes for the future of your country, and for Africa on the whole?

We are with the people who rise up and claim their rights and their freedom. It all takes time though. And we aren’t naïve: It’s all about politics, private interests, and finance… all this that is preventing people’s rights to be respected. We still have hope for negotiations and peace talks, but today our main way to help is to spread the message through our music all around the world. Hopefully soon we’ll be back home for playing to our Tuareg community. –by Bret Love; all photos provided by Tinariwen

If you enjoyed our interview with Tinariwen, you might also like:

INTERVIEW: Baba Salah on al-Qaeda’s Invasion of Mali

INTERVIEW: Nigeria’s Seun Kuti

INTERVIEW: Senegal’s Baaba Maal

INTERVIEW: Sierra Leone Refugee All-Stars