Congo Square is quiet now. Traffic forms a dull drone in the distance. A lone percussionist taps out ancient tribal rhythms on a two-headed hand drum. An air compressor used in Rampart Street road construction provides perfectly syncopated whooshes of accompaniment.

Shaded park benches are surrounded by blooming azaleas, magnolia trees and massive live oaks that stretch to provide welcome relief from the blazing midday sun. It’s an oasis of relative solitude located directly across the street from the French Quarter.

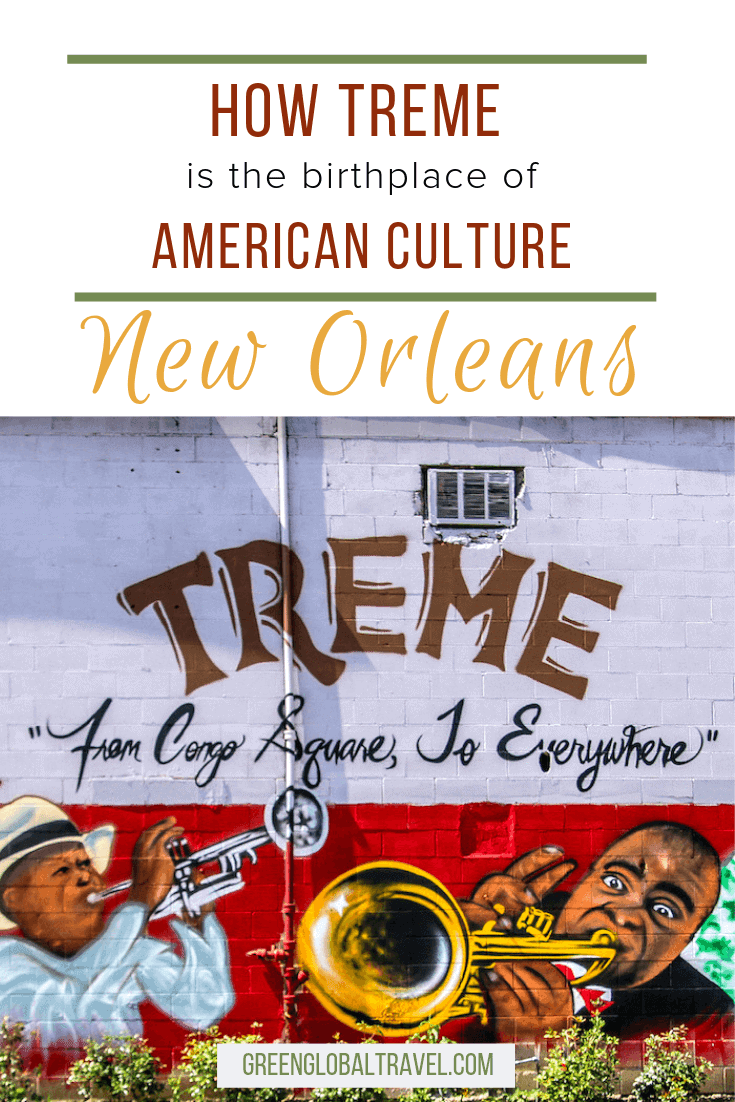

CONGO SQUARE

Congo Square is quiet now, but in the 18th and 19th centuries this “Place des Nègres” would teem every Sunday with slaves (given the day off under France’s Code Noir) and free people of color.

Over 500 people would gather here in fur, fringe, shells and bells to celebrate their African and Creole cultural heritage, playing music, singing and dancing, buying and selling goods in the market.

This area– now part of Tremé, New Orleans‘ oldest African-American neighborhood– was the only place in America where African and Afro-Caribbean people were allowed to preserve their cultural traditions for over a century.

When these traditions were blended with those of the European colonialists, it gave birth to a distinctly American fusion that continues to define our nation today.

Congo Square is quiet now. But it’s here that the seeds of American culture as we know it were sown more than 200 years ago. And the scents, sounds and sights that originated here have never been more vital to New Orleans than they are now, more than a decade after Hurricane Katrina devastated the city.

SITTING DOWN AT DOOKY CHASE WITH LEAH CHASE

Originally known as the Faubourg Tremé and named after real estate developer Claude Tremé, this quiet neighborhood’s tiny size (.69 square miles) belies its global influence.

Located just a block west of the suburb’s center, Dooky Chase’s Restaurant is an iconic landmark of New Orleans history, providing a crucial connection to the city’s past that was almost wiped away by the 2005 storm.

Its regal owner, 92-year-old Leah Chase (whose life story inspired the character of Princess Tiana in Disney’s The Princess & the Frog), remembers the early 20th century importance of the neighborhood to her family, all Creoles de Couleur.

“The Creoles of Color worked in homes and picked up the same culture as the white people,” she says. “They’d go to the Opera House, where they had their [racially segregated] upstairs corner. They had réveillons at Christmas and New Year’s, held a St. Augustine Church and Congo Square. The Tremé was the big thing for Creoles of Color.”

Down the street from St Augustine, which was designed by French architect J.N.B. de Pouilly (who also worked on Jackson Square’s St. Louis Cathedral) and remains the oldest African-American Catholic parish in the nation, there was a red-light district known as Storyville.

Established by the New Orleans City Council in 1897 to regulate prostitution, Storyville was popular with travelers, many of whom heard jazz (played by guys like Jelly Roll Morton and Buddy Bolden) there for the first time. Word of this lively new sound quickly spread far beyond the confines of Tremé and drew more visitors to the city.

Chase, who moved to the area at age 14 in 1937 to attend St Mary’s Academy, developed a passion for Creole cooking inspired by her grandparents. She was among the first African-Americans to work as a waitress in the French Quarter in 1940, when men shipped off to fight in World War II.

When she married popular jazz musician Edgar “Dooky” Chase II (whose parents originally owned Dooky Chase’s) in 1945, the strong-willed 22-year-old knew she wanted to make changes at the casual restaurant.

“When I got here, I said, ‘We’ve got to do better than fried chicken, fried fish and fried oysters! We have to do what [upscale white restaurants] do!’ The first thing I put on the menu was Lobster Thermidor, and the people threw a fit,” she recalls with a laugh. “They told my mother-in-law I was going to ruin her business! I had to back up and give them what they like.”

Chase poured her heart and soul into creating a menu steeped in Creole tradition– sumptuous dishes such as gumbo, red beans and rice and chicken Creole– whose roots could be traced back to West Africa.

Alongside soul food hotspot Willie Mae’s Scotch House, Dooky Chase’s put Tremé on the culinary map, influencing future icons like Paul Prudhomme and Emeril Lagasse. Though New Orleans was still racially divided in the 1950s, whites and blacks alike lined up to dine at Miss Leah’s tables.

During the ‘60s, Thurgood Marshall and Martin Luther King, Jr. broke bread and discussed strategy with local freedom fighters such as Reverend A.L. Davis and Oretha Castle Haley in the upstairs meeting room at Dooky Chase’s. But despite the fact that her restaurant became a de facto headquarters for Civil Rights in Louisiana, Chase says most people her age didn’t understand the movement.

“We thought those young people were crazy as bats!” she laughs. “We were brought up not to offend people to get what we want. But sometimes you have to, and they knew that it had to be done. I helped them do it by feeding them. Some would go to jail and [Civil Rights lawyer A.P. Touro] had to go get them out. They’d clean up, come back here and eat again.

“They planned all their strategy right here over a bowl of gumbo,” she continues. “I tell young people today, sometimes you just need to sit down and talk. You may not agree on everything, but you can work together to work it out. But if you don’t sit down at the table, it’s not going to happen. You can change the world over a bowl of gumbo!”

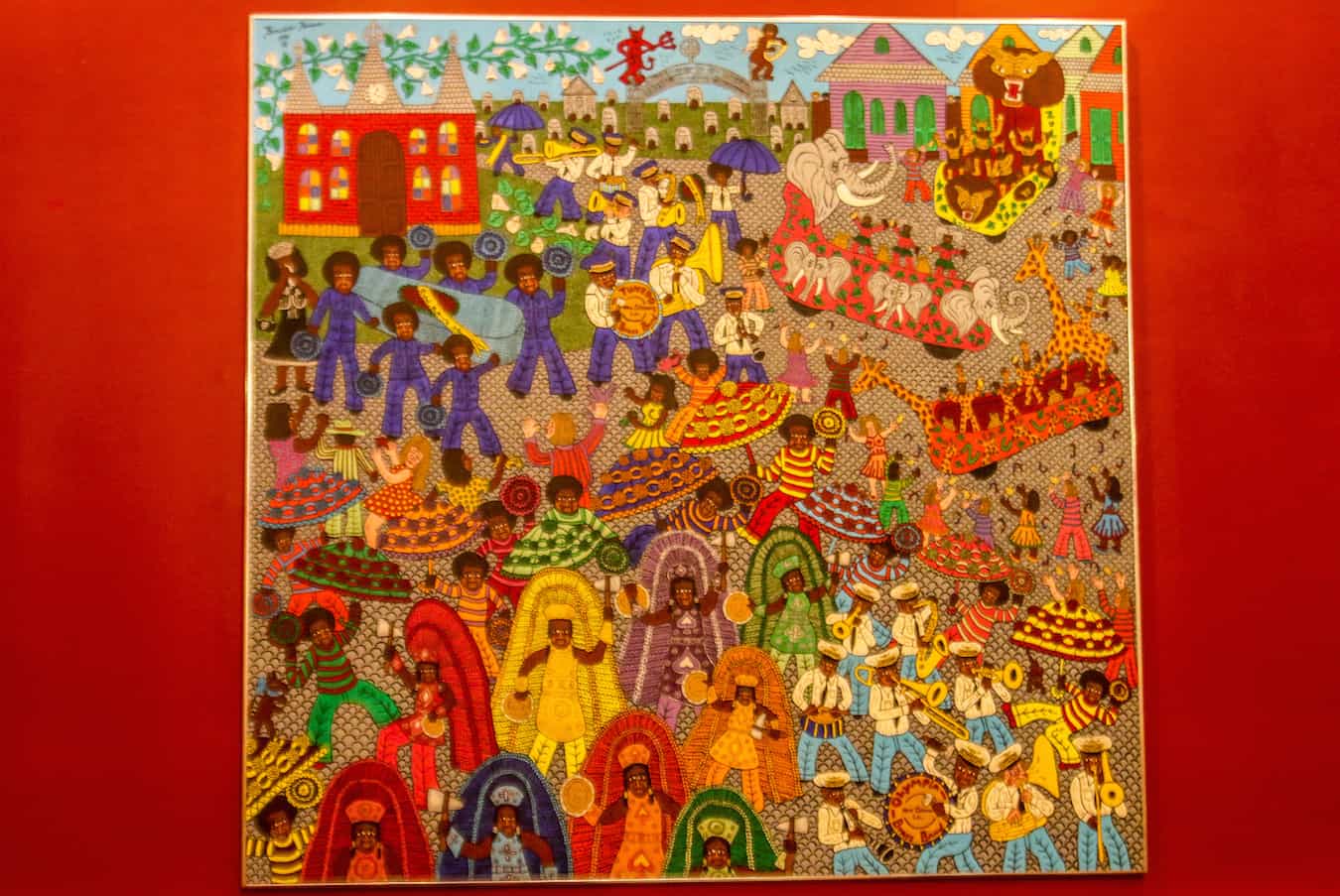

As the world outside began to change, Tremé became increasingly integrated, attracting an eclectic mixture of artists, activists and other open-minded progressives. At the urging of her friend Celestine Cook, Chase ran for a position on the Board for the New Orleans Museum of Art (where blacks had been barred from entry until the mid-‘60s) and won.

She sat down at the table with icons such as sculptor Elizabeth Catlett, painter Jacob Lawrence and poet Maya Angelou. She learned to view art as an investment– not just financial, but a cultural investment in her community.

She gradually lined the walls of Dooky Chase’s with what many consider to be New Orleans’ finest collection of African-American art, telling vivid visual stories that run the gamut from ancient tribal West Africa to modern-day Louisiana.

By the late 20th century, Chase had not only established herself as the Queen of Creole Cuisine, but also as one of Tremé’s preeminent civic and cultural leaders.

She nearly lost everything when Hurricane Katrina descended on New Orleans on August 28, 2005. “It was terrible: 80% of this city was underwater. In the restaurant, we had five feet of water in some places. I was in Birmingham and one of my grandsons, a fireman, called to tell me that Dooky Chase’s was destroyed, but the art was still intact.”

The community quickly rallied around her to save the beloved Tremé landmark. Firemen and policemen volunteered to help move her art collection to Baton Rouge. Companies such as Popeyes and Starbucks donated $50,000 to $150,000. The restaurant community held a Holy Thursday benefit dinner and raised an additional $40,000.

Less than two years after Katrina’s devastation, Dooky Chase’s reopened.

Miss Leah acknowledges that Tremé looks a lot different now. Some former residents passed away, others moved on after the storm. Many houses are being rebuilt or refurbished.

The housing projects that used to stand across the street from Dooky Chase’s are gone, replaced by more well-built, energy-efficient buildings. There’s even a brand new school, the John Dibert Community School. While some critics carp that these are signs of gentrification, Chase sees them as signs of hope for the future.

“On that school, you see a tribal symbol of a dove looking backwards,” she says. “The bird is looking back to see how he can go forward. That’s what we have to do here in New Orleans. People are coming together, helping one another, and understanding one another more than ever before… And it all starts with sitting down at the table.”

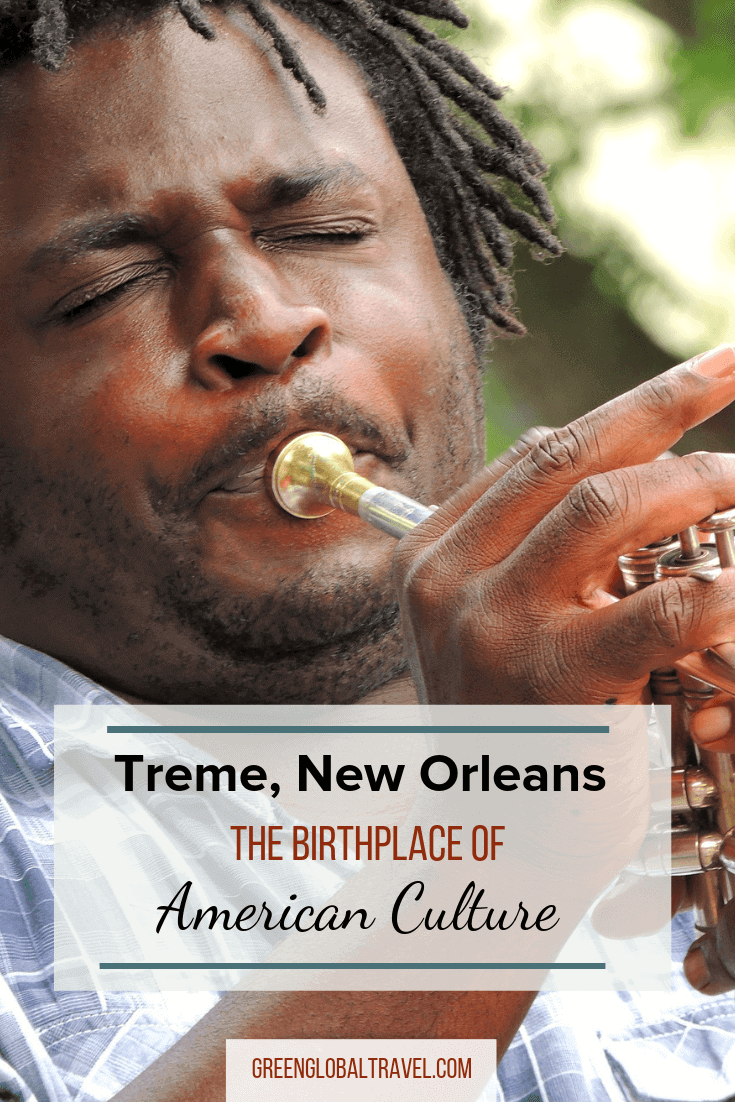

AMERICAN MUSIC ROOTS

There’s a look of sheer bliss on Donald Harrison Jr’s face as he taps out syncopated rhythms on snare drum and cowbell to accompany the infectious “Un Na Nay” chants being led by two members of the Wild Magnolias tribe of Mardi Gras Indians for a visiting school group.

We’re here at Preservation Hall, a few blocks from Congo Square, to discuss how the African culture allowed to survive in Tremé gave birth to nearly every popular music form of the 20th century.

But right now Harrison– world-renowned jazz saxophonist, Big Chief of the Congo Square Nation Afro-New Orleans Cultural Group, and creative consultant on the HBO series Treme– is deep in the pocket of a groove that simply won’t quit.

According to Harrison, that groove is the throbbing heart of global culture.

“The fact that they let Africans play drums in Congo Square is one of the root influences of American music,” he insists. “Those rhythms influenced jazz, blues, rock ’n’ roll, soul, funk and now hip-hop. You can hear it in Elton John, playing New Orleans-style piano. You can hear it in the rhythms of the Rolling Stones and James Brown. That sound was taken all around the world.”

Schooled by his music-loving father (Guardians of the Flames Big Chief Donald Harrison, Sr.) and legendary drummer Art Blakey (with whom Donald played in the ‘80s), Harrison traced the roots of jazz back to the late 1800s, when African-American sounds merged with military brass band traditions.

Blacks refused coverage by insurance companies formed “Social Aid & Pleasure Clubs,” whose benefits included an annual parade and a brass band for funerals. Dances banned from Congo Square after the slave revolt of 1811 made their way into funeral marches, exaggerated into a syncopated strut.

Early icons like Jelly Roll Morton, Baby Dodds and Louis Armstrong emphasized the rollicking swing of the beat, and the New Orleans “Second Line” sound was born.

According to Harrison, the history of Jazz and Mardi Gras Indians are inextricably intertwined, with both emerging from Tremé.

“When you listen to early jazz men talk about Congo Square and Jelly Roll Morton talking about Mardi Gras Indians, you realize there’s a connection,” he says.“The syncopation and call-and-response came out of the tribal influence. Jazz had that influence, but also had French opera and military marches. They syncopated the marches, which gave you happy feet, and you started dancing because you couldn’t help yourself. Tremé was the first neighborhood where all of these cultural ideas melded. We’re very fortunate that this city allowed some traditional aspects of African culture to be kept alive.”

That history is very much alive in New Orleans today. You can feel it in the sold-out crowds at Preservation Hall, Irvin Mayfield’s Jazz Playhouse and Snug Harbor Jazz Bistro, one of many lively music clubs on bustling Frenchmen Street.

You can feel it in Tremé’s 32-acre Louis Armstrong Park (home to Congo Square and the Mahalia Jackson Theater for Performing Arts), where Elizabeth Catlett’s statues pay tribute to Armstrong, saxophonist Sidney Bechet and cornetist Buddy Bolden.

Perhaps most importantly, you can feel it in the vibrant music of Trombone Shorty, Rebirth Brass Band, Glen David Andrews and the Young Fellaz Brass Band, many of whom grew up in Tremé.

READ MORE: Preservation Hall & New Orleans

Like Leah Chase (whose Creole cuisine his father introduced him to at an early age), Harrison sees educating the younger generation as essential to preserving New Orleans’ distinctive culture.

“Miles Davis, McCoy Tyner, Art Blakey… these guys passed their way of thinking onto me. I made up a new curriculum of teaching music for the Tipitina’s Foundation because I wanted to ensure the next generation got that information, so they could expand upon it.”

Tipitina’s has given out millions of dollars in instruments to local high schools to keep band programs going. There are a lot of people like myself, dedicated to making sure these traditions are kept alive so that we can move it forward. This culture,” Harrison insists, “is an American treasure.”

KILL ‘EM DEAD WITH NEEDLE & THREAD

Where Chase and Harrison were surrounded by Creole cuisine and jazz all their lives, Dow Edwards found himself on the outside of Mardi Gras Indian culture looking in.

He became infatuated with their immaculately crafted suits and infectious chants as a boy, after seeing a bloody confrontation between rival gangs on Mardi Gras. But he didn’t know anyone in the community, and ultimately left for college in Oklahoma.

The former New England Patriot receiver– now partner at a respected New Orleans law firm– didn’t begin working his way up through the ranks to become Spy-Boy (the scout responsible for running point and signaling the Big Chief in case of trouble) of the Mohawk Hunters tribe until 2008.

“After Katrina hit, it looked like there might be a run on some of the cultural icons of New Orleans,” he recalls. “Mardi Gras Indians are very neighborhood-associated, but Katrina disbursed everybody and whole neighborhoods were taken out. Being a lawyer and having served on several boards, I thought I could lend a voice to the Indians.”

“The first meeting I went to,” he continues, “Big Chief Tyrone Casby’s wife had somebody draw my first patch on cardboard and he showed me how to sew beads on. I thought, ‘There’s no way I’m ever gonna finish this suit!’ But the joy I had on Mardi Gras day when I put that suit on… there’s a sense of spirituality and community pride that comes from this long process.”

Visiting Tremé’s Backstreet Cultural Museum and Ronald Lewis’ House of Dance & Feathers, you begin to piece together the murky history of Mardi Gras Indian culture. Its origins date back to 1725, when the first African slaves escaped into the bayou with help from the Choctaw and other tribes.

They were taught to live off the land in “Maroon Camps,” and many of them banded together with the Indians for the Natchez Revolt of 1729. Records suggest Creoles of Color were dressing as Indians to celebrate Mardi Gras as early as 1746, and intermingling of the races led to a boom in mulatto babies.

In the 1800s, African-Americans were forbidden to march or mask in parades. So the Mardi Gras Indian tradition remained underground for decades, dividing geographically into loosely organized gangs.

READ MORE: New Orleans’ Mardi Gras Indians

They would gather secretly to sing and chant in the ancient tribal tradition, fashioning suits festooned with fish scales and bottle caps to pay tribute to the Indians who had helped them obtain their freedom. On Mardi Gras day, when police were busy protecting the French Quarter, they took to the streets of Tremé to strut their stuff.

Sometime in the mid-20th century, there was a significant effort to make Mardi Gras Indians more mainstream-accessible.

“This has always been a backstreet, territorial-type culture,” Edwards admits. “Sometimes Indian gangs would cross paths and real fights would break out. But Big Chiefs Tootie Montana (Yellow Pocahontas), Bo Dollis (Wild Magnolias) and Donald Harrison, Sr. came together to talk about how to regulate it better. They decided the chief’s job is to protect his tribe and make sure each Indian got home safe. So they changed their motto to, ‘Kill ‘em dead with needle and thread.’”

Now, instead of physical dominance, Mardi Gras Indians strut, sing and compete to be “the prettiest.”

Edwards spends an average of five hours a day in his workshop, sewing remarkably intricate suits that have earned him a reputation as a master craftsman. Using thousands of dollars worth of beads, gems and decorative feathers, he creates artfully complex tapestries that tell stories from African-American and Native American history.

He wears each suit just three times, parading on Mardi Gras, St Joseph’s Night (March 19), and the Sunday after St Joseph’s Day, known as “Super Sunday.”

Super Sunday is like a family-friendly Mardi Gras without the floats or brass bands. Today, all focus is on the Indians.

Walking down Lasalle Street towards A.L. Davis Park before the parade with his spectacular green suit displayed on a rolling riser, Edwards is greeted like a rock star: People stop and stare, children point and smile, and friends rush over to pound his fist.

As we walk the 3-mile parade route, photographers descend upon him like vultures and countless people praise his work: “You the prettiest!”

Later, Edwards speaks passionately about why being a Mardi Gras Indian matters.

“We still have economically depressed neighborhoods in New Orleans. We try to bring joy to those people and empower them to feel good about themselves. This kid came up to me one Super Sunday and said, ‘I wanna be like you.’ I said, ‘Do you wanna be an Indian like me, or a lawyer like me?’ He said, ‘Both.’ I want to teach that kid he can overcome any obstacle!”

“Along with people like [Donald’s sister] Cherice Harrison, who founded the Mardi Gras Indian Hall of Fame, we go into schools and talk about this culture and where it all began. We teach them how to sew. We do it in Tremé, Algiers, and throughout New Orleans. We teach these kids how to be empowered to do the things they want to do, and even things they think they can’t do. Once people learn what we do, there are more kids and more people who want to help the tradition continue to grow.”

READ MORE: Mardi Gras Indians Super Sunday: NOLA’s Next Generation

CODA

Congo Square is quiet now, but Tremé’s traditions, rhythms and lessons live on.

Its robust flavors are in every bowl of gumbo served up by Leah Chase and her daughter, Stella. Its soulful sounds are in every note Donald Harrison, Jr. teaches as leader of the Trombone Shorty Academy, which targets underserved, musically gifted high school students. Its strong sense of cultural pride is woven into every patch Dow Edwards teaches those schoolchildren to sew.

Congo Square is quiet now, but its voices have grown louder in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. It’s almost as if the threat of losing everything has reminded the people of New Orleans the incredible value of the storied history too many people took for granted.

There’s a growing appetite for the preservation of these cultural treasures, evidenced by the rapid rise in attendance at Super Sunday, the lines that stretch for blocks outside Preservation Hall, and the wait for a table at Dooky Chase’s during weekday lunch rush.

Congo Square is quiet now. But its influence will continue to echo and reverberate around the world long after all of us have passed on. –Bret Love; photos by Bret Love & Mary Gabbett unless otherwise noted

The New Orleans Treme’ Walking Tour – is a great way to see the major landmarks of this cultural watershed yourself with a local guide.

Our visit to New Orleans was sponsored in part by the New Orleans CVB. But we will never compromise our obligations of integrity to our readers. Our opinions remain solely our own.

If you enjoyed our story on Treme, New Orleans, you might also like:

LOUISIANA: Mardi Gras Indians Celebrate Super Sunday in New Orleans

INTERVIEW: Ben Jaffe on Preservation Hall Jazz Band & New Orleans

LOUISIANA: The Best Oysters in New Orleans

LOUISIANA: An Insider’s Guide to Mardi Gras in New Orleans

LOUISIANA: Charmed at New Orleans’ Historic Voodoo Museum

LOUISIANA: Cajun Food Tours in Lafayette