It all started with the elephant.

It was my first safari drive on my first afternoon at Londolozi Private Game Reserve, part of Sabi Sands Private Game Reserve, on the western border of South Africa’s Kruger National Park. I piled into the elevated middle row of an open-backed Land Rover along with a German couple, Heinz and Uta; a tracker named Eckson; and our ranger/driver, Solomon.

We drove past the Londolozi gate, through scrub-laden bushveld and into an open savanna where sparse trees created striking, angular profiles against the horizon. We saw several small birds and butterflies in a cornucopia of colors, but few mammals for the first hour aside from a haughty herd of hippos in a small pond, who seemed none too pleased by our presence.

But eventually we spotted him– a majestic bull elephant feeding on leaves from a thicket of trees perhaps 75 feet to our left. As Solomon deftly wheeled the vehicle around to get a better view, there was a tense moment of trepidation in which it seemed like the massive male might turn tail and run. But the shrewd ranger simply backed off, cut the engine and waited patiently.

Slowly but surely, the elephant came closer and closer to investigate. It seems laughable to describe a 12,000-pound African bush elephant– the world’s largest living terrestrial mammal– as “creeping,” but he moved with a mixture of curiosity and caution. When the elephant got to within 40 feet I whispered to Solomon nervously, wondering if perhaps he was going to charge us. But he calmly assured me that the elephant’s body language suggested otherwise.

READ MORE: 50 Interesting Facts About Elephants (for World Elephant Day)

“Oh my god…” I said in awe, jaw agape, as he moved to within 30 feet, then 20, and stopped no more than 15 feet from us. Every camera stopped clicking, every voice was silenced in hushed reverence, as he raised his trunk towards us and sniffed the air. Time seemed to stand still and stretch as he sized us up. The encounter lasted mere minutes, but his powerful presence made it feel much longer.

Eventually he turned, sauntered casually over to the nearest tree, bent it over as if it were merely a matchstick to get at its fresh foliage, and resumed feeding. I was surprised to realize that tears were streaming down my face. Suddenly, this dream-like African adventure felt overwhelmingly real.

THE ROOTS OF INSPIRATION

I grew up in a lower middle class, racially mixed neighborhood on the east side of Atlanta. For my family, travel meant backpacking in the north Georgia mountains, spending a week at my grandparents’ trailer on Lake Hartwell, or making the 5-hour drive down to Panama City Beach. I learned how to clean a fish, plant a garden, and forage for wild blackberries at an early age. Though I was raised in the city, nature became my sanctuary.

By the time I was a teenager, the “white flight” that plagued many cities in post-integration America had altered our community. My high school was 98% black, 1.5% Asian and .5% “miscellaneous,” with less than 50 caucasians in a school of 2000+ students. I became equally influenced by white and black culture, with rock, pop and post-punk on one side and soul, funk and R&B on the other. While my white friends blasted Aerosmith and Skynyrd, I preferred Kraftwerk and Africa Bambaataa.

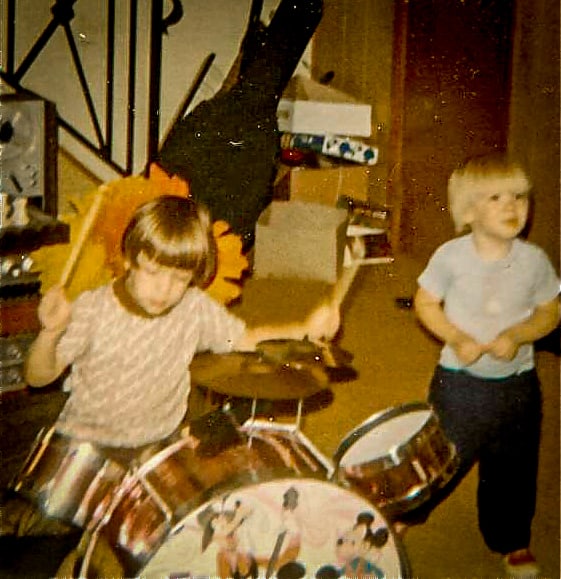

A budding singer-songwriter and an avid music lover whose parents listened to everything from Mozart and Miles Davis to Ray Charles and the Beatles, I built up a record collection as eclectic as it was extensive. I couldn’t travel the world, so I became addicted to exploring its cultures instead, with music as my passport.

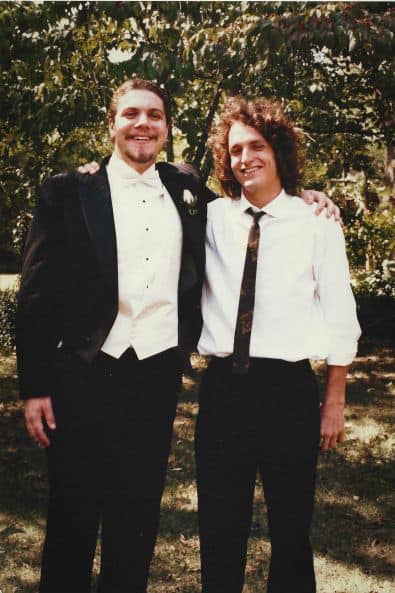

My passion led me to become a Music Business major (with a Music Theory minor) at Georgia State University. I studied music history, with a particular focus on the evolution of music from the African-American diaspora. It was through GSU and our after-school jobs at a local pizzeria that I became best friends with Tony Giarrusso, who would eventually inspire my dreams of Africa.

At first Tony and I couldn’t have been more different on the surface: I was a long-haired, arty extrovert with tattoos and earrings, while he was a soft-spoken, seemingly conservative science major. We connected through our mutual love of music– jazz, funk, reggae and hip-hop in particular– frequently trading CDs that inspired us.

With him on bass and me on vocals, we ultimately formed a band together and began working our way up on the Atlanta music scene. I was working part-time for a major record label at the time, and used my connections to garner some interest from local A&R reps for our alternative rock-rap sound. Remember that this was the early ‘90s, when such things were not yet considered trendy.

But then fate threw a curveball in the face of my rock star aspirations: Upon graduating from college, Tony decided to go into the Peace Corps and shipped off to teach fish farming in the central African nation of Burundi, one of the poorest countries in the world. I quit playing music professionally shortly thereafter, ultimately embarking on a burgeoning career as a music journalist instead.

Tony and I kept in touch regularly over the next five years as he moved from Burundi to Gabon to Zambia, with only brief visits home in between. Every month or two I would send him a package filled with new music, magazines and letters from home, and he would send back African music, photos and letters about his life in Africa. Our friendship gradually grew deeper, despite the distance.

I knew the kids in his tiny village by name. I learned about the local customs, and began to research the differences between their cultural traditions. He explained how different it was living in a dirt-floor hut and eating foods many westerners might consider distasteful, and how he came to be accepted as a member of his host’s family. I came to love Africa for the myriad complexities of what it really was, as opposed to the idealized European vision of what it’s supposed to be.

Tony was the first person I ever knew personally who went on an African safari. The stories he brought home from his trip to Tanzania, which included incredible photos and National Geographic-worthy video of a lion on top of a floating hippo carcass defending his prize from hostile crocodiles, left me delighted for him and increasingly determined to see Africa for myself.

CONSERVATION IN ACTION

When I finally made it to South Africa in 2000, it was the culmination of an intensely personal dream seven years in the making. All of these memories washed over me as we drove on towards the South African sunset, which streaked the evening sky with warm shades of blue, purple and magenta.

We soon stopped for our first “sundowner” (the British term for a break at the end of the workday, in this case with cold Castle Lagers and the dried, cured meat known as biltong) at the crest of a hill that provided stunning savanna views in all directions. I asked Solomon, a handsome African in his late twenties who had a remarkable breadth of knowledge of the myriad plants and animals that inhabited this fertile land, how he became a ranger.

READ MORE: Inspirational Animal Rights Activists (15 Female Heroes)

“I grew up in a village just outside the reserve,” he explained. “Conservation Corporation Africa [which owned Londolozi then, and is now known as &Beyond] hires local people as guides because they believe it’s important to practice responsible ecotourism. By giving people jobs, it encourages them to protect wildlife instead of shooting the animals for food, or to protect their cattle.”

This was the first time I’d ever heard the word ecotourism, which I later learned was defined as “Responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment and improves the well-being of local people.” At the time, all I knew was that Londolozi was the most ambitious and impressive blend of conservation and tourism I’d ever seen in my travels.

The myriad heart-pounding sightings I had during my few days in the reserve remain among the most exciting travel experiences of my life even now, 15 years later.

READ MORE: What Is Ecotourism? (The History & Principles of Responsible Travel)

There was a female leopard deep in the shrub, who walked close enough to our Land Rover that I could’ve easily reached down and stroked her fur.

Solomon slowly followed behind her as she stealthily stalked her way through the dense thicket and into a clearing. We watched her Mexican standoff with a gangly giraffe and an anxious wildebeest who had gotten separated from the herd.

As the sun set, she climbed 10 feet up into a small tree and nestled into the crotch of two big branches.

There was one epic, eventful morning drive in which we spotted four giraffes galloping like elegant supermodels, a mama rhino and her adorable calf grazing on verdant green grass in black soil after a controlled burn, more elephants, and a huge herd of skittish zebras.

Later that night, we saw a cheetah nursing three 6-week-old cubs, a lumbering hippo, two cackling hyenas in pursuit of frightened impalas who bounded across the road in a desperate attempt to escape, and a pride of 13 lions sprawled out like enormous house cats across the road just outside the Londolozi gate (some slept lazily, while others groomed one another as two males stood watch).

But the memory that brings a big smile to my face and a wellspring of emotion to my heart occurred on our last day in the reserve, when we had a chance to witness the importance of wildlife conservation in action.

Our guide, Paul, received a call about an emergency at nearby Singita Lodge, with which Londolozi had strong ties. A pack of 16 endangered African wild dogs (of which 250 remain in 7,580-square mile Kruger National Park), had escaped the reserve and were pacing the fence’s perimeter.

Because the dogs occasionally kill goats, sheep and other cattle, some farmers shoot them on sight. Londolozi’s guides were asked to monitor the pack’s position until the head ranger could advise on how to resolve the situation.

We followed for 15 minutes, watching as the scouts ran in search of a way back into the park, with the precious pups kept in the middle of the pack for protection. Eventually the lead dog found a spot he liked and began digging madly at the base of the fence.

There was an intense energy among the three vehicles as the alpha male dug his way under and squeezed through the hole. I couldn’t suppress an exuberant “Wooohooo!!” as the entire pack ran back into the sanctuary where it belonged.

It seemed fitting to learn that Londolozi was Zulu for “protector of all living things.”

I left the private game reserve feeling remarkably enlightened and truly inspired by these rangers, who were devoted to understanding, protecting and educating visitors about the wildlife that makes Kruger National Park such an extraordinary place.

But it was just the beginning of a life changing experience in South Africa that would forever transform the way I choose to travel, and the work to which I now dedicate my life.

THE AFTERSHOCKS OF APARTHEID

After learning about the crucial role of tourism in funding wildlife conservation, I got a much more intensive education on the racial and economic imbalance of post-apartheid South Africa during my week in KwaZulu Natal.

Known as “the garden province,” this coastal region is the heart of Zulu country, and has given birth to important leaders such as Nobel Peace Prize winner Albert Lutuli, African National Congress (ANC) founder Pixley ka Isaka Seme, South Africa President Jacob Zuma and 19th century Zulu chief Bhambatha, who resisted colonial forces and became an icon of the anti-apartheid movement.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the area has also been home to some of South Africa’s most difficult sociopolitical struggles, from the late 1800s Anglo-Zulu War to the turmoil of the present day.

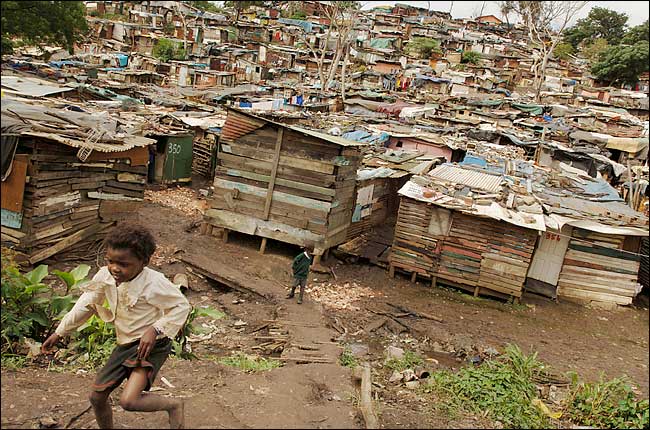

I witnessed South Africa’s economic disparity firsthand en route to the Drakensberg mountains, which stretch over 1000km from the Eastern Cape north to KwaZulu Natal.

The pothole-laden roads required reduced speed, allowing us to observe villages filled with ramshackle shanties fashioned from found wood and road signs. The street was crowded with hundreds of people– farmers, shepherds and miners– whose average income is less than $150 a month.

Their tattered rags stood out in stark contrast to the crisp, pressed blue and white uniforms of their smiling schoolchildren.

In Durban I met up with passionate cultural activist Gail Snyman for her Coloured Experience Tour, which served to reinforce how divided South Africa’s three racial classes (black, white and “coloured,” or those of mixed racial heritage) had been during apartheid.

We began at the Human Rights Wall, a strikingly colorful mural outside the old Durban prison painted to commemorate the political prisoners who’d served time there. Different sections of the vivid work addressed myriad issues facing post-apartheid South Africa, including racism, rampant misuse of power, uneven wealth distribution and HIV/AIDS.

“Many people are still wary of the African National Congress government,” Snyman explained, “and some believe we were actually better off under apartheid. Things are getting better, and there are some people and NGOs working to improve the situation. But change comes slowly, and many people still feel disenfranchised by a divisive history of oppression.”

READ MORE: Kigali Genocide Memorial: Rwanda History, from Colonialism to Genocide

Snyman, who is of mixed descent, took me to the ghetto of Wentworth township, which was created by apartheid in Durban’s industrial South Basin area. She recalled moving there in 1959, after the Group Areas Act forcibly divided the people of South Africa by race into new residential areas.

Like many slums in America, Snyman’s neighborhood was plagued by crime, drug abuse, gang violence and unemployment, not to mention cancers caused by industrial pollution from nearby oil refineries.

Rich with historical and sociological background, Snyman’s tour balanced insightful political observations with wry humor, as she detailed apartheid’s atrocities and absurdities in equal measure.

We went from the “Rainbow Chicken” community’s shabbily-rigged shanties (in which the poorest blacks lived); to the first coloured settlement, White Town (named for the color of its limestone walls); to Millionaires Mile, a white area whose homes offered exceptional views of the Indian Ocean.

As we made our way through the township to our final stop, Gail revealed the personal impact the apartheid-era government’s racial policy had on her family. “My uncle, who’s fair-skinned and blue-eyed, was labelled as white,” she recalled. “My mother, who looks Asian, was considered colored, which essentially meant that she and her brother could have no communication.”

We pulled up to a quaint little house in the suburb of Merewent, whose add-on construction reminded me of the mobile homes of America’s rural south. This was the home Gail had grown up in. She explained that, since the apartheid government prevented coloured people from expanding their tiny homes, her family had built a small garage, which they later turned into an apartment for Gail and her husband after the requisite government inspection.

Gail’s mom, a petite but lovely lady of Malaysian descent, was in the kitchen cooking us some deliciously spicy “bunny chow,” a popular South African street food consisting of curried meat and/or veggies cooked inside a homemade loaf of bread. As we ate, her mom pulled out photo albums of Gail as a child, and soon we were all laughing at family stories and licking juices from our fingers like old friends.

Sitting in this working class community, eating lunch with a family whose cultural background was very different from my own, somehow felt very familiar to me. Like my native Atlanta, Durban was a melting pot metropolis divided by racial segregation, looking for a new way forward after centuries of political oppression ended by a strong Civil Rights movement.

As I hugged Gail and her mother goodbye, I could only hope that South Africa would find a way to right history’s wrongs and heal the damage done.

THE SPIRIT OF ITHEMBA

The next day I made my way north from Durban, visiting Eshowe’s Fort Nongqwayi (the British Army’s HQ during the height of the Anglo-Zulu War) and the Zululand Historical Museum along the way before my final stop at Simunye Zulu Lodge.

After greeting my host/interpreter, Patrick, I climbed into an ox cart for the slow, extremely bumpy 5km descent into the heart of Zulu territory. Gorgeous mountain vistas greeted us at every turn as we made our way down into the verdant valley, with acacia trees and aloe palms all around us. At the bottom of the trail, we crossed a bridge over the tranquil Mfule River and entered the Pioneer Camp.

With no other travelers there during my stay, I settled into The Eagle’s Nest, the uppermost of six rustic rock rooms built into the side of a cliff overlooking the valley. The accommodations were spartan but cozy, with a zebra-skin rug, lanterns the only source of light, and a cold trickle of water in the stone shower. It all felt primitive and perfect, like something you might have found in Africa 100 years ago.

The roots of Simunye date back even further. The family that owns the property, the Biyela clan, reportedly traces its lineage back to legendary warrior Mkhosana, who famously led the regiment that defeated the British at Isandlwana.

Now, the Biyelas work to preserve historic Zulu cultural traditions, introducing visitors to customs in danger of dying out due to the homogeneity of globalization.

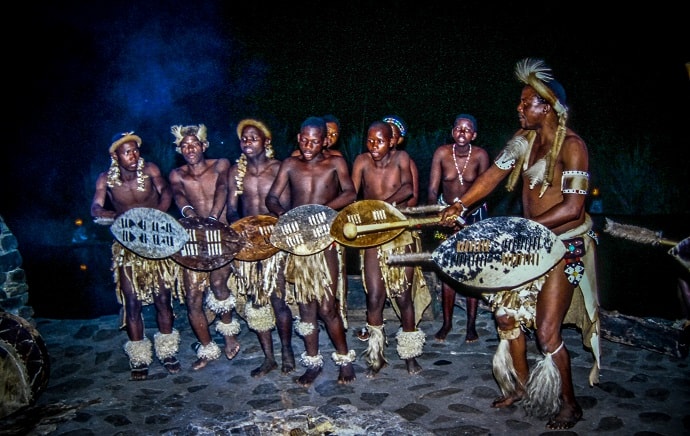

At sunset Patrick and I made our way back across the river and up the hill to the kraal– a traditional African village enclosed by a fence– where he taught me a typical Zulu salutation required before you’re allowed to enter the village.

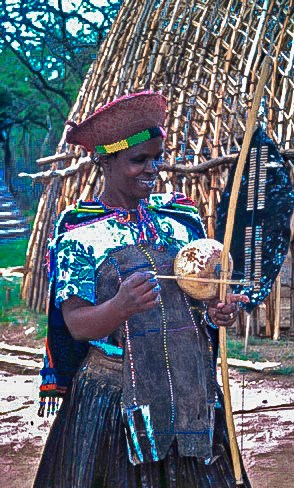

We were greeted by the clan’s patriarch, Gelenja Biyela, who dressed in the traditional tribal wear of a chieftain, including a variety of animal skins, beads and a massive Zulu shield.

Once inside, we sat around a fire at the heart of the chief’s compound as his wife welcomed us with earthly-tasting Zulu beer, his bare-breasted daughters washed and dried our hands, and his muscular sons offered delicious homemade sausage served fresh from the fire.

As Patrick led me back across the bridge for dinner, a dozen or so Zulus leapt out from behind big bushes, and I must have leapt several feet in surprise. We all had a good laugh as they walked with us to the dining pavilion, serenading me the entire way. Thunderous drums greeted us there, pounding out a syncopated rhythm that reverberated throughout the valley.

With torches and a big bonfire providing the only light, it was a dramatic setting for an invigorating performance by the entire Biyela family.

Even the chief joined in their four-part polyphonic harmony, whose call-and-response style was at the root of many of the musical forms I’d studied back in college. If you’ve ever heard Ladysmith Black Mambazo, you know the South African sound I’m talking about: Sweet, spiritual and dripping with soul.

Eventually the singing stopped and the music built in dynamic intensity as the girls danced shyly. Then the testosterone-fueled boys showed off their high-stepping moves, with each trying to outdo the other, before inviting me to join them and give it my awkward best.

Thankfully I didn’t fall and bust my butt, and the Zulus all smiled at my earnest attempt to match them kick for kick.

As dinner wound down and the family returned to their village, a guitarist sat down on a log by the fire and began playing a buoyant tune, singing along in a harmonious voice that moved me in a way I can’t explain.

I zoned out of the conversation I was having, distracted by the sheer beauty of this moment in the middle of nowhere, touched by a song whose words I could not understand.

I found myself tapping on the table in rhythm to the music, and impulsively urged Patrick to ask the musician if I could play with him. He looked at me quizzically as I asked the woman behind the bar for a knife and a mostly empty ketchup bottle, then led me over, introduced me to Malsothosotho and suggested I sit beside him.

The guitarist grinned as I began tapping out a simple beat, and we quickly locked into a groove rooted in the South African townships I’d explored just a few days earlier.

“How do you know the Zulu rhythms?” the bartender, Eunice, asked me with an incredulous smile after the song ended.

“I don’t,” I replied honestly. “I just play what I feel.”

“You play wonderfully!” she said, squeezing my hand firmly in assurance.

Emboldened with confidence, I started singing in call-and-response with Malsothosotho, echoing his Zulu words phonetically and singing harmonies I’d learned from listening to Paul Simon’s Graceland.

What started as a tentative collaboration gradually grew bolder and louder. Seemingly everyone from the Zulu village– now dressed in shorts and t-shirts rather than loincloths– came back across the river to listen to and applaud our impromptu performance.

It was a surrealistic high I’ll never forget, and the memory still gives me goosebumps today.

The next morning, Malsothosotho’s strummed guitar and lilting voice provided my all-time favorite wake-up call. Though he spoke little English and I knew no Zulu, we greeted each other warmly, bonded as brothers through the universal language of music. He led me down to breakfast, and then across the bridge to the village, playing guitar and singing as I smiled from ear to ear.

The next few hours offered an introduction to the Zulu way of life, including cattle farming, exploring a typical family’s hut, learning to make home-brewed beer, spear-fighting practice, and traditional crafts. But soon it was time for me to make the long journey back home, and we walked over to the horses they’d saddled for Patrick and I to ride out on.

Malsothosotho, looking clearly emotional, came over and asked Patrick to translate for him. “He says he would like to give you a Zulu name,” Patrick said, explaining that it meant a lot to the musician that I wanted to sing and play music with him.

“I will call you Ithemba,” Malsothosotho said in surprisingly decent English, putting his hand on my heart for emphasis. “It means hope. You give me hope for the future of Africa.” Once again my eyes welled up with tears as we embraced warmly and said our goodbyes.

TRANSFORMED BY TRAVEL

Although we spent less than 36 hours together, I’ve never forgotten Malsothosotho, that moment, or those words. And as much of an impact as my time at Simunye Zulu Lodge may have had on him, my two weeks in South Africa inexorably changed my life in ways I never expected.

I went home eager to learn everything I could about the principles of ecotourism, and how responsibly managed travel could be used to fund the conservation of vital ecosystems such as that of Kruger National Park and vibrant cultures such as that of the Zulu, and possibly restore economic balance to communities like Merewent.

Though I spent 15 years building up my name writing about entertainment for publications ranging from the Atlanta Journal-Constitution to Rolling Stone, I gradually moved more into travel writing in order to share my passion for ecotourism in the hope that my stories might encourage others to travel more responsibly and sustainably.

But, perhaps most importantly, South Africa taught me the benefits of traveling differently, of being a participant rather than merely an observer, of getting to know the locals who define the character of a place, and of letting go of the comforting familiar and embracing the unknown.

And in doing so, I have found that people from cultures all around the world are more similar beneath the surface than our petty prejudices might lead us to believe.

Fifteen years after my last trip to the continent, I can still feel Africa’s distinctive rhythms pulsating through my veins, calling to me like a siren from some distant land. And as I prepare to return this week for the first time since that life changing experience in 2000, I know that she has even greater lessons left to teach me. –Bret Love

If you enjoyed our post on my Life Changing Experience in South Africa, you might also like:

INTERVIEW: Ladysmith Black Mambazo on Apartheid & Nelson Mandela

INTERVIEW: South African Legend Johnny Clegg, “The White Zulu”

ECO NEWS: The Connection Between Walking With Lions & Canned Lion Hunting

ECO NEWS: Killing for Conservation- Can Hunting Save the Black Rhino?

PHOTO GALLERY: The Wilds of Amboseli National Park & Timbavati Game Reserve

What is an Eco Lodge? A Guide to “Green” Accommodations

Easy Ecotourism: 10 Simple Steps to More Sustainable Travel

The Benefits of Ecotourism: 20 Travel Bloggers on the Importance of Nature Travel